On August 7, 1782, as the American Revolutionary War drew toward its uncertain conclusion, General George Washington issued a general order from his Newburgh, New York headquarters that would lay the foundation for one of the most enduring military honors in United States history: the Badge of Military Merit. At a time when the Continental Army was starved of resources, wracked with discontent, and overshadowed by the aristocratic traditions of European military decorum, Washington’s gesture was both revolutionary and radical. Unlike other awards that honored generals and noblemen for grand feats, the Badge of Military Merit was designed specifically to recognize the sacrifices and valor of common soldiers—particularly those who had been wounded in action or performed extraordinary service.

The award was symbolically crafted in the shape of a heart made of purple cloth, a deliberate departure from the gold medallions and jeweled orders that European monarchies bestowed on their elite officers. Purple, long associated with nobility, was here transformed into a democratic symbol of courage and suffering. Washington’s order was explicit: the badge would be granted “whenever any singularly meritorious action is performed” by enlisted men, a recognition of their often-overlooked role in achieving American independence.

It was, in many ways, a manifestation of Washington’s republican ideals—bestowing honor not by birthright but by merit and sacrifice. He entrusted the distribution of the badge to regimental commanders, empowering the decentralized and often ragtag army to recognize its own heroes. Only three men are known to have received the original Badge of Military Merit during the war: Sergeant Elijah Churchill, Sergeant William Brown, and Sergeant Daniel Bissell Jr. Their citations noted acts of extraordinary bravery in the face of the enemy.

After the Revolutionary War ended, however, the badge fell into disuse. The young republic, wary of standing armies and martial pomp, did not institutionalize a formal system of military decorations. For nearly a century and a half, the memory of Washington’s heart-shaped badge remained buried in dusty archives, a footnote in the annals of early American military history.

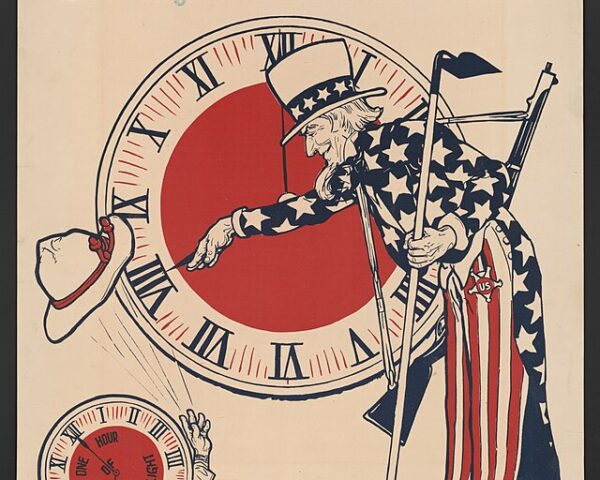

It was not until the eve of another global conflict—World War II—that the idea was revived and transformed. On February 22, 1932, the bicentennial of Washington’s birth, General Douglas MacArthur reintroduced the award under a new name: the Purple Heart. Now minted in metal rather than cloth, and bearing Washington’s profile in relief, the modern medal retained the shape and color of the original badge. But its criteria had evolved. Rather than being granted for general merit, the Purple Heart would henceforth honor U.S. military personnel wounded or killed in combat.

This shift reflected the changing nature of warfare—and the nation’s evolving relationship with its servicemen and women. The carnage of mechanized war and the rise of the citizen-soldier demanded a more formal recognition of sacrifice. From the beaches of Normandy to the mountains of Afghanistan, the Purple Heart became a solemn and ubiquitous emblem of personal cost and national service.

Today, the Purple Heart remains one of the most recognized and emotionally resonant military honors. While it carries no monetary reward or promotion, it symbolizes a bond between the soldier and the republic—a quiet acknowledgment of suffering endured in defense of the nation’s ideals. That its origins lie not in a Pentagon directive, but in the handwritten orders of a weary general at the end of a desperate revolution, makes it all the more powerful.

George Washington’s creation of the Badge of Military Merit in 1782 was not simply a battlefield decoration; it was an assertion of American values. It democratized honor, elevated sacrifice, and challenged the Old World notion that only the elite deserved commendation. In the humble purple heart of cloth, stitched into history on that August day, one can see the seeds of a national ethos: that courage belongs not to the few, but to the many who serve.