On the night of August 14, 1791, deep in the forested hills of northern Saint-Domingue—the French colony that was the richest sugar producer in the world—a group of enslaved Africans gathered in secrecy for a Vodou ceremony at a place called Bois Caïman (“Alligator Wood”). The meeting was led by Dutty Boukman, a towering figure among the enslaved population and a houngan, or Vodou priest. Alongside him was the mambo (priestess) Cécile Fatiman. In the candlelit darkness, as drums pounded and chants filled the air, the assembled men and women pledged to rise against their masters. The moment has since been enshrined in history as the spiritual and symbolic spark of the Haitian Revolution.

Saint-Domingue in 1791 was a study in stark contrasts: dazzling wealth for a small white planter elite, grinding brutality for the half-million enslaved Africans who toiled on sugar, coffee, and indigo plantations. Mortality rates were so high that the enslaved population depended on constant importation from Africa. Many retained strong ties to African cultures, languages, and religious practices, including Vodou—a syncretic faith blending West and Central African spiritual systems with Catholicism. Planters feared Vodou both for its cultural cohesion and for its potential as a medium of resistance. Their fears were justified.

The Bois Caïman ceremony fused the political and the sacred. According to later accounts, Boukman delivered a fiery exhortation, urging unity and vengeance against the planters. A black pig was reportedly sacrificed, and participants swore an oath of secrecy and solidarity, calling on the lwa (spirits) to bless their cause. While historians debate the exact details—much of what we know comes from hostile colonial sources or oral tradition—the symbolic power of the gathering is undeniable. It represented both a rejection of the planter order and a declaration of self-liberation.

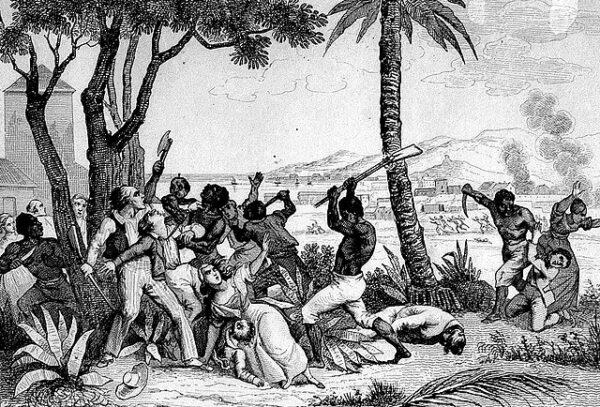

Within a week, on the night of August 21–22, the northern plain erupted in violence. Thousands of enslaved men and women, many armed with machetes and makeshift weapons, set fire to cane fields, sugar mills, and plantation houses. The revolt spread with astonishing speed, overwhelming local militia forces. Boukman himself was killed in battle within the first months, but the insurrection he helped ignite could not be extinguished. It evolved into a complex, thirteen-year struggle involving shifting alliances among rebel leaders, Spanish and British intervention, and the eventual rise of Toussaint Louverture as the revolution’s central figure.

The Haitian Revolution would become the first successful slave uprising in the modern world and the only one to result in the founding of a free state governed by former slaves. When Haiti declared independence in 1804, it shattered the myth of Black inferiority that underpinned the Atlantic slave system and sent shockwaves through the colonial world. For planters across the Americas, Bois Caïman became a byword for insurrectionary terror; for the enslaved, it was a beacon of hope.

In Haitian national memory, the ceremony has taken on an almost mythic status. It symbolizes not only the beginning of the revolution but the fusion of African cultural resilience with the political will to destroy slavery. Each August, commemorations in Haiti and among the diaspora honor the gathering, emphasizing its role in affirming both spiritual identity and the right to freedom.