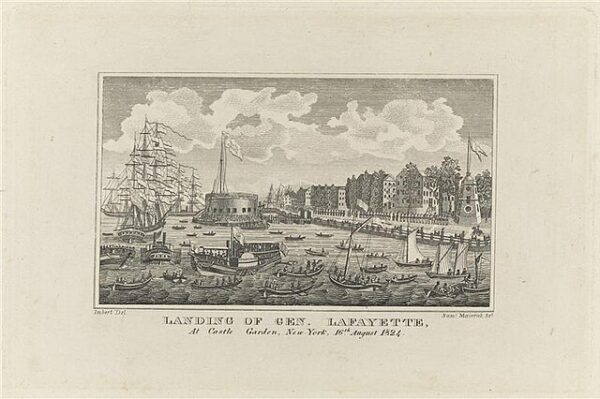

In the waning light of a summer’s afternoon on August 15, 1824, a crowd of unprecedented size pressed against the wharves of New York Harbor, eyes fixed upon the stately vessel Cadmus as church bells rang to welcome a hero. On its deck stood a figure whose very presence summoned the memory of another age — Gilbert du Motier, the Marquis de Lafayette, the last surviving French general of the American Revolutionary War. At sixty-seven, he had crossed the Atlantic again, not as a soldier, but as a guest of the nation he had once fought to create.

Lafayette’s arrival marked the beginning of an extraordinary, year-long tour that would carry him through all 24 states of the still-young republic. The invitation, extended by President James Monroe and endorsed by Congress, was no mere gesture of gratitude. It was a deliberate act of national memory — an effort to bind the Revolutionary generation to its successors before time erased the last living links to independence.

To the citizens of 1824, Lafayette was more than a historical figure. He was a living embodiment of the alliance with France that had tipped the scales against Britain, a symbol of youthful idealism, and — in an era increasingly conscious of the nation’s expanding boundaries and democratic experiment — a reminder that the American cause had once inspired the world. His military service under George Washington at Brandywine, his winter at Valley Forge, and his role in securing French support were by now part of the nation’s civic scripture.

New York’s welcome was nothing short of operatic. Salutes from ships and fortifications thundered across the harbor. Flags and bunting draped buildings. Bands struck up martial airs, mingling with the cheers of tens of thousands who had crowded the waterfront. Contemporary accounts spoke of men and women weeping openly as the aging general set foot on American soil for the first time in nearly forty years.

From New York, Lafayette’s itinerary unfolded with a precision that reflected both the logistical challenges of early 19th-century travel and the fervor of civic pride. Cities competed to outdo one another in pageantry. In Philadelphia, he was received in the Hall of Independence beneath the very walls where the Declaration had been adopted. In Boston, veterans of the Revolution — some bent with age, others still erect in bearing — greeted him in uniforms faded but still proudly worn. At every stop, receptions, parades, and banquets blurred into a continuous ovation.

Yet Lafayette’s tour was not simply a parade of nostalgia. It happened during a transition for American politics. The “Era of Good Feelings” under Monroe was giving way to the fractious politics that would define the election of 1824, with John Quincy Adams, Andrew Jackson, Henry Clay, and William H. Crawford vying for the presidency. Lafayette, careful to avoid overt partisanship, nevertheless found himself embraced by all factions as a neutral hero, a man above the political fray.

For the general himself, the journey was as much a personal pilgrimage as a diplomatic mission. He visited the tomb of Washington at Mount Vernon, pausing for long moments of silent reflection. He traveled to battlefields where his youthful courage had been tested, often in the company of survivors who recounted shared hardships with a vividness undimmed by decades. He met with ordinary citizens in towns and villages far from the centers of political power, extending the hand of friendship with a warmth that contemporaries found disarmingly genuine.

By the time Lafayette completed his circuit in 1825, the tour had become one of the most ambitious expressions of public gratitude in the nation’s history. It reinforced a shared sense of Revolutionary heritage at a moment when regional and political divisions were beginning to grow. And it reintroduced to a new generation the ideal of service to principle over self — an ideal Lafayette himself had embodied as a young aristocrat who had risked fortune and life for a cause not his own.