The 1972 Munich Olympics were meant to symbolize renewal. West Germany, scarred by its Nazi past, sought to project a liberal, cosmopolitan image to the world: “the Games of peace.” Instead, Munich became synonymous with massacre. Over the days of September 5 and 6, eight members of the Palestinian faction Black September scaled the unguarded fence of the Olympic Village, turned dormitories into killing grounds, and seized the world’s attention through the barrel of a gun. Eleven Israeli athletes and coaches would be dead by the end of the ordeal, along with a German policeman.

The attack began with brutality. Wrestling coach Moshe Weinberg was shot while resisting; weightlifter Yossef Romano was slain and then mutilated in a display calculated to terrify. Nine others were taken hostage. Black September’s demands—the release of more than 200 prisoners in Israel and two jailed German radicals—were less a serious bid for negotiation than a declaration of presence. They had chosen the Olympics precisely because the world was watching, and they understood that terror’s potency lies in its horrifying spectacle.

The Germans, still determined to prove themselves humane after the atrocities of the Third Reich, stumbled into paralysis. They rejected Israel’s offer to send commandos. They refused military-style solutions, improvising instead with untrained local police. What unfolded at Fürstenfeldbruck airbase on the night of September 5–6 was chaos disguised as rescue. Disguised policemen abandoned their posts, ill-equipped snipers could not coordinate, and when the firing began, the outcome was catastrophe: grenades tossed into helicopters, athletes bound together and riddled with bullets, and Anton Fliegerbauer, a young policeman, shot dead in the exchange.

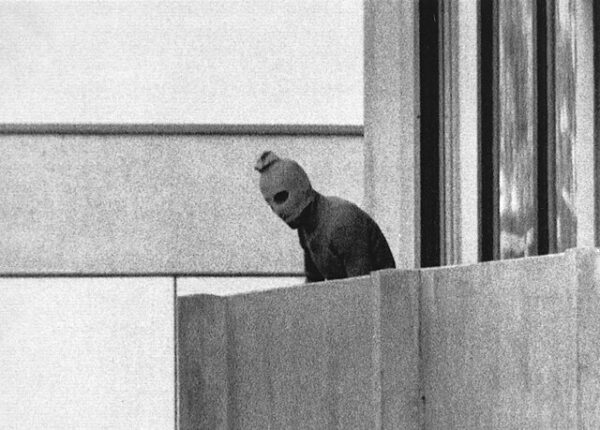

Television carried the drama into living rooms worldwide: masked gunmen on balconies, negotiators in trench coats, the flicker of floodlights at the airbase. For the first time, international terrorism was not merely reported; it was performed on a global stage, calibrated for a new age of mass media. The very institutions meant to embody unity and peace—the Olympics, the host nation, the international press—were turned into instruments of terror’s amplification.

For Israel, the consequences were existential. Golda Meir rejected any suggestion of bargaining. Jews, she insisted, would not again “go like sheep to the slaughter.” Out of that resolve emerged Operation Wrath of God, the long campaign of clandestine reprisals against those who had planned and executed Munich. In Israel’s political theology, the massacre confirmed a permanent lesson: survival required not only vigilance but vengeance, a refusal ever to be passive in the face of annihilation.

For West Germany, the debacle marked humiliation. The postwar determination to shed the image of militarism had left the state incapable of defending its guests. Only in the ashes of Munich did the Federal Republic create GSG 9, an elite counterterrorism unit modeled on Britain’s SAS, a tacit acknowledgment that “Never Again” required force as well as contrition.

And for the Olympic movement, the massacre destroyed the illusion that sport could remain insulated from politics. The decision to resume competition after only a brief memorial service exposed the tension at the heart of the Games: ideals of peace colliding with the evil of radical terrorism.