On September 8, 1760, a drama that had unfolded across the North American wilderness reached its decisive conclusion. In the heart of New France, Montreal—last stronghold of French power in Canada—formally surrendered to the British. With that act, the long and bloody struggle of the French and Indian War (the North American theater of the Seven Years’ War) reached a turning point that would reverberate not only across the continent but also in Europe, where diplomats were already calculating the balance of empires.

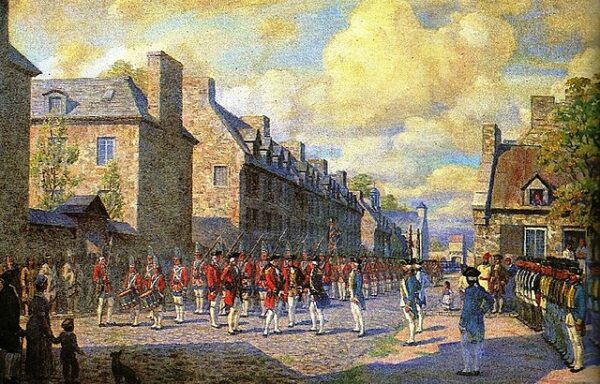

The surrender did not come suddenly. For three years the British had pressed relentlessly into the French interior, seizing Louisbourg in 1758, Quebec in 1759, and now, finally, Montreal. The French forces under Governor General Pierre de Rigaud, Marquis de Vaudreuil, were surrounded: General Jeffrey Amherst approached from the west, advancing down the St. Lawrence from Lake Ontario; Brigadier General James Murray marched up from Quebec; and William Haviland pushed north from Lake Champlain. This three-pronged campaign was no accident but a carefully executed encirclement designed to crush French resistance once and for all. By September, the trap had snapped shut.

Montreal was not a city fortified like Quebec. It lacked the dramatic cliffs and defensive works that had allowed General Montcalm, the French commander killed the previous year at the Plains of Abraham, to hold off British attacks for months. Instead, Montreal was vulnerable, exposed on an island in the St. Lawrence, its supply lines shattered and its defenders weary. Vaudreuil faced the reality that further resistance would mean slaughter for both soldiers and civilians. Negotiation, however humiliating, seemed the only path.

The terms of surrender reflected both pragmatism and the shifting codes of imperial war. Amherst, whose reputation for severity was well earned, nonetheless granted relatively generous conditions. French regular troops were allowed to return to Europe, transported under British safeguard. Canadian militiamen were sent home, their lives spared but their political future now tied to the British crown. Catholic clergy retained freedom to continue their ministry, though under Protestant rule. For the civilian population—some 70,000 French settlers—the capitulation marked the end of their allegiance to France and the uncertain beginning of life as British subjects.

Yet beneath these formalities lay deeper consequences. The conquest of New France completed Britain’s continental ascendancy. By eliminating French power in Canada, the British gained control of the vast interior of North America, from the Great Lakes to the Ohio Valley. The French dream of a transcontinental empire, linking the St. Lawrence to the Mississippi, was extinguished. For Native nations who had allied with the French, the surrender was ominous. Many had fought not out of loyalty to France but to preserve a balance of power that checked British expansion. With Montreal’s fall, that balance collapsed. The years to come would bring Pontiac’s Rebellion and a new cycle of conflict, as Indigenous resistance confronted the advancing British frontier.

In France itself, the loss of Canada was a bitter humiliation but not, in the eyes of policymakers, a fatal blow. Some French statesmen dismissed the colony as “a few acres of snow.” Caribbean islands such as Guadeloupe and Martinique, with their lucrative sugar plantations, seemed to matter more to the calculus of wealth and power. Still, the psychological impact was immense: the fleur-de-lis no longer flew over the St. Lawrence, and the myth of French permanence in North America had been shattered.

The capitulation of Montreal in 1760 represented the culmination of a war that reconfigured global empires and foreshadowed future revolutions. For Britain, the conquest promised dominion over an immense new continent, but also burdens of governance, defense, and debt that would soon strain relations with its own American colonists. For France, the defeat revealed both the limits of imperial ambition and the vulnerabilities of overextension. And for the people of Canada, it marked the end of one allegiance and the beginning of another, an imperial transition whose legacy still shapes North America.