In a year already crowded with photographic firsts, Sir John Herschel quietly added another milestone on September 9, 1839: the first successful image fixed on glass. The achievement, overshadowed at the time by the announcements of Louis Daguerre in Paris and William Henry Fox Talbot in London, set in motion a line of innovation that would shape photography for the rest of the nineteenth century.

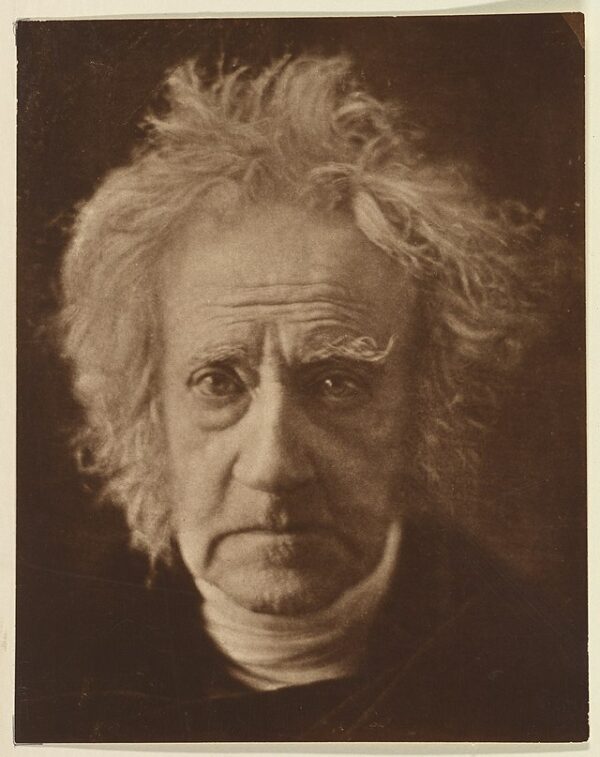

Herschel, the son of astronomer William Herschel and himself a scientist of formidable range, was no stranger to discovery. He catalogued stars, devised chemical processes, and coined the very words “photography,” “positive,” and “negative.” Unlike Daguerre, who secured a French state pension, or Talbot, who guarded his calotype patents, Herschel had little interest in commercial exploitation. He worked in the spirit of open science, testing how far the chemistry of light could be pushed.

On that September day, he coated a pane of glass with a light-sensitive solution and exposed it to the sun. The result was faint but unprecedented: a photographic image suspended within the transparency of glass. Where Daguerre’s polished copper plates offered reflection and Talbot’s papers absorbed light into fibers, Herschel’s glass plate suggested clarity, permanence, and a new kind of luminosity.

The experiment was not immediately practical. Preparing and handling glass required precision, and the plates were fragile in use. But the principle mattered. Two decades later, Frederick Scott Archer’s wet collodion process would turn Herschel’s test into a workable method, making glass plates the dominant photographic medium of the mid-nineteenth century. Portrait studios, battlefield photographers, and scientific expeditions would all rely on glass negatives, proving the foresight of Herschel’s early trial.

Historians have often asked why Herschel’s role remains less celebrated than Daguerre’s or Talbot’s. The answer lies partly in temperament. Herschel treated photography as a branch of natural philosophy rather than an invention to be monetized. He published freely, declined patents, and contributed his terminology and technical insights to others. His generosity enriched the field but dimmed his public profile.

Still, the significance of September 9 endures. Herschel’s glass plate revealed a future in which photographs could be projected, duplicated, and studied with a precision impossible on paper or metal. The same principle would carry forward into lantern slides in lecture halls, the Civil War negatives preserved in archives, and the mass production of portraits that defined the Victorian age.

Herschel’s reputation rests on a lifetime of work that spanned astronomy, chemistry, and mathematics, but his experiment with glass photography distilled his approach: curious, methodical, and unselfish. In the fragile clarity of that first plate, he offered not a finished process but a vision—a glimpse of how light itself might become the historian of its own passage.