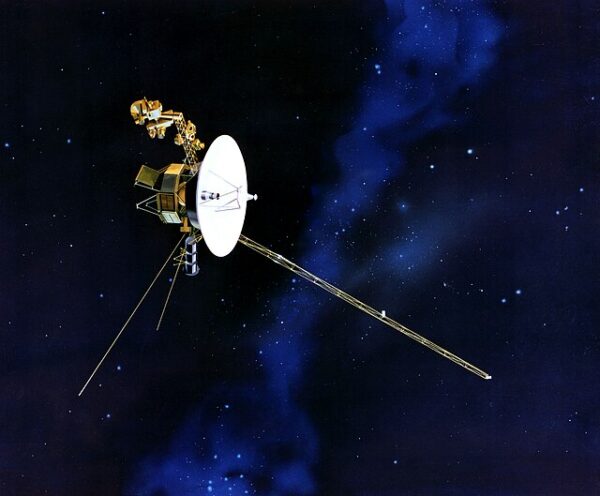

On September 12, 2013, NASA announced what many had long awaited but few dared to fully believe: Voyager 1, the space probe launched in 1977, had officially crossed the threshold into interstellar space. After nearly 36 years in flight, the little spacecraft that once carried the hopes of a generation—and a golden record of Earth’s sounds and greetings—became the first manmade object to leave the bubble of the Sun’s influence and enter the vast unknown between the stars.

Voyager 1’s passage was not a sudden leap but a gradual, almost imperceptible transition. Scientists had debated for months, even years, about whether the craft had already crossed the heliopause, the boundary where the solar wind yields to the pressures of interstellar plasma. The problem was measurement. At distances more than 11 billion miles from Earth, signals take over 17 hours to reach mission control, and the environment itself is complex: charged particles, shifting magnetic fields, and overlapping data streams confounded easy interpretation.

What clinched the case in 2013 was the behavior of plasma waves. In March of that year, a burst from a distant solar eruption rippled outward, striking Voyager 1 months later. The probe’s instruments recorded oscillations that revealed the surrounding plasma to be far denser than anything found inside the heliosphere, matching theoretical predictions of the interstellar medium. With that, scientists declared with confidence that Voyager 1 had gone where no machine, and no human dream, had gone before.

The feat was less a triumph of speed than of endurance. Voyager 1 travels at about 38,000 miles per hour, swift by earthly standards but sluggish compared to the immensity of the cosmos. Launched alongside its twin, Voyager 2, in 1977, the probe’s original mission was to take advantage of a rare planetary alignment that would allow a “grand tour” of the outer solar system. Over the next decade, Voyager 1 sent back images and data that transformed human understanding of Jupiter and Saturn: swirling storms in Jupiter’s atmosphere, active volcanoes on its moon Io, the delicate complexity of Saturn’s rings, and the hazy mystery of Titan’s atmosphere.

By 1980, having completed its planetary assignment, Voyager 1 was aimed on a trajectory that would eventually carry it out of the solar system. What followed was a long, slow outward drift. In 1990, at Carl Sagan’s urging, NASA commanded the spacecraft to turn its camera back toward Earth and snap the “Pale Blue Dot” photograph—our planet appearing as a faint speck in a sunbeam, an image that became one of the most iconic testaments to human humility and aspiration.

By the time of its interstellar crossing, Voyager 1 had been traveling more than three decades beyond its last planetary encounter. Its instruments, though aged and limited, continued to function thanks to plutonium power sources that generate electricity from radioactive decay. Yet the probe’s days are numbered. NASA engineers estimate that by the mid-2020s, the spacecraft will no longer have enough power to run its instruments. Even then, Voyager 1 will continue on, silent and inert, drifting among the stars for perhaps billions of years.

The confirmation of Voyager 1’s interstellar status was both a scientific milestone and a cultural moment. For scientists, it opened a new era of exploration, providing the first direct measurements of the interstellar medium. For the public, it was a reminder of the audacity of the 1970s mission planners who sent two small spacecraft outward with no guarantee of success but with immense confidence in human ingenuity.

And for those inclined to think philosophically, Voyager 1’s crossing was a quiet affirmation of endurance in the face of vastness. Long after the societies that built it have changed beyond recognition, long after the engineers and scientists who guided it have passed away, Voyager 1 continues its journey outward. It carries with it not just instruments and data, but the traces of a civilization that once looked up at the night sky and chose to reach for it.

As NASA’s Ed Stone, the mission’s chief scientist, put it at the time: “We’re in a new region of space where nothing has ever been before. For the first time, we are truly interstellar travelers.”