On September 14, 1814, the gray half-light of dawn, after a night of fire and thunder, the smoke parted over Fort McHenry to reveal what the British had failed to erase. The flag—thirty by forty-two feet, stitched in Baltimore only weeks earlier—still flew defiantly above the battered ramparts. For Francis Scott Key, an attorney stranded on a truce vessel in the Patapsco, that banner’s survival was more than a military signal. It was revelation, proof that a young republic could endure the empire’s wrath, and it compelled him to put pen to paper in the moment of relief.

The defense of Baltimore had begun in disaster. Washington lay in ashes—its Capitol and President’s House torched in retaliation for American incursions into Canada. To the British, Baltimore appeared the next and more profitable target: a city of shipyards and privateers, whose commerce had harried their fleets throughout the war. On September 12, they landed their forces at North Point. The Maryland militia gave ground but inflicted a blow of their own—felling Major General Robert Ross, the seasoned commander who had ordered the sack of Washington.

The following day, the real test began. British warships anchored within range of Fort McHenry, the five-pointed bastion that barred entrance to the harbor. Vice Admiral Alexander Cochrane ordered his guns to speak, and for twenty-five hours they did—mortars lobbing shells in long arcs, Congreve rockets hissing like serpents through the air. Inside the fort, Major George Armistead’s garrison of barely a thousand men endured. They huddled in bombproofs, patched walls, returned fire when they could. All through September 13, the heavens glowed with flashes, as if day had been shattered into fragments and strewn across the night.

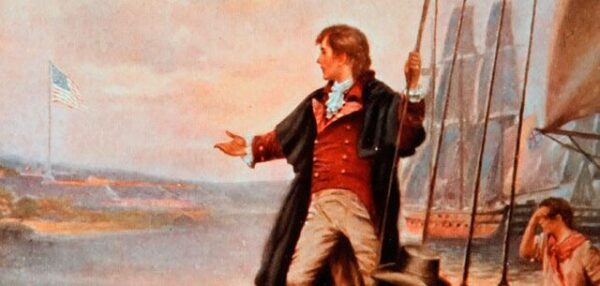

It was from a distance of eight miles that Key absorbed the spectacle. He had not come as a combatant but as an intermediary, pressing for the release of Dr. William Beanes, a Maryland physician taken prisoner. The negotiations had succeeded, but the British would not let Key depart until their assault concluded. Thus confined, he watched through the long night as rockets burst above the fort. At times the bombardment fell eerily silent, and in the void he imagined defeat—that the flag had been struck, the fort surrendered. Yet when dawn finally broke, the haze lifted, and the immense garrison standard was there still—ragged, but visible, immense against the morning sky.

Key’s immediate response was to draft lines on the back of a letter. The verses captured the peril of the night and the improbable relief of the morning: “O say can you see, by the dawn’s early light…” Published in Baltimore within days under the title Defence of Fort McHenry, the poem was soon set to the tune of “To Anacreon in Heaven,” a melody already familiar to American ears. What began as one man’s private exclamation spread rapidly, taken up in taverns, parades, and encampments, until the opening stanza alone—culminating in the phrase “land of the free and the home of the brave”—assumed a quasi-sacred place in the national imagination.

The larger war would grind on into 1815, concluded not by victory but by exhaustion on both sides. Yet the failure of the British assault on Baltimore marked a symbolic turn. Washington might burn, but Baltimore would stand. And in that endurance, Americans discerned a lesson: that their republic, however vulnerable, was not so fragile as their enemies presumed.

More than a century later, in 1931, Congress would consecrate Key’s lines as the national anthem, enshrining them in civic ritual. But their origins remain bound to that September morning, when the battered flag above Fort McHenry proclaimed survival, and a young nation, scarcely four decades old, insisted upon its right to endure.