On September 16, 1776, the morning broke with British horns sounding not the call to arms, but the mockery of a fox-hunt. From the wooded ridges above Harlem, George Washington’s battered Continentals listened to the taunt. For weeks they had known only retreat — from Long Island, from New York City itself. Now, jeered as prey, they would answer with teeth.

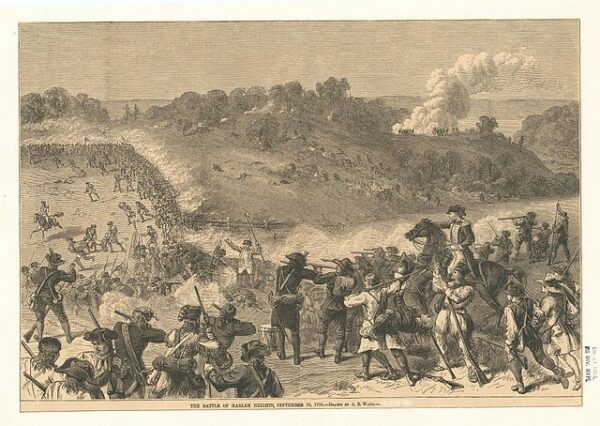

The skirmish that followed was no grand set-piece battle, but it was the first time the fledgling army had pressed its enemy and held the ground. On that September day, amid fields and orchards north of Manhattan, the Americans traded volleys with seasoned British light infantry and Hessian allies. They gave as good as they got — and more.

It began with a probing advance by Crown forces. Redcoats and jägers pushed northward, forcing back American pickets. Colonel Thomas Knowlton’s rangers and Virginia riflemen under Major Andrew Leitch fought hard, but they fell back under the press of superior numbers. The British, convinced of their quarry’s weakness, sounded the bugle in mock sport. Washington, watching from the ridge, chose defiance over retreat.

His orders were clear: harass the British frontally while Knowlton and Leitch led a flanking column. The maneuver, rough through thickets and broken ground, fell short of its intended sweep. Leitch was struck down early; Knowlton soon after. Yet their men pressed on, pouring fire into the enemy’s flank and stiffening the fight. Washington committed reinforcements. For hours the musketry echoed across Harlem’s fields as Americans, emboldened, surged down the ridgeline.

The sight unsettled British regulars unaccustomed to being driven back by provincials. By midday, pressed and harried, the redcoats withdrew toward their main camp. Casualties told the story: British losses approached 90 killed and wounded, while American casualties numbered about 30. Small in scale, but heavy in meaning.

Washington’s army had stood firm. More than that, it had counterattacked and forced a retreat. For soldiers who only days before had scrambled in panic through New York streets, the taste of victory was intoxicating. The Continental commander understood the moment’s value. “This little advantage,” he wrote, would have “greatly animated our troops.”

There was loss, too. Knowlton, remembered alongside Nathan Hale as a patriot who gave his life in New York that autumn, fell in the thick of the fight. Washington mourned him as “a brave and gallant officer.” Yet even in grief, the army drew strength from the day.

Strategically, Harlem Heights changed little. Howe’s army still held New York City and the initiative. Within weeks, Washington would again be in retreat, yielding ground in a campaign of attrition. But September 16, 1776, marked a turning point in spirit.

The Revolution had not collapsed into flight and despair. On the heights above Harlem, the foxes bared their teeth — and for the first time since Boston, the hunters pulled back.