On September 18, 1850, the United States Congress passed and President Millard Fillmore signed into law the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, one of the most divisive and consequential pieces of legislation in American history. As part of the Compromise of 1850—a fragile political bargain meant to ease sectional tensions between North and South—the act dramatically strengthened federal authority in the capture and return of runaway slaves in exchange for the statehood of a free California and a western border for slavery that ended at the Texas state line. Its passage not only deepened the moral and political rift over slavery but also set the nation more firmly on the path to civil war.

The law was designed to appease Southern slaveholders who feared the erosion of their property rights under the Constitution’s fugitive slave clause. Since the original Fugitive Slave Act of 1793, many northern states had passed “personal liberty laws” to hinder enforcement, while abolitionist networks like the Underground Railroad helped thousands of enslaved people escape. By 1850, Southern leaders demanded a tougher statute as the price for accepting California’s admission as a free state and for tolerating restrictions on slavery in other western territories.

The act went far beyond previous federal measures. It required that any person, free or enslaved, suspected of being a fugitive could be seized without the benefit of a jury trial or even the right to testify in their own defense. Instead, cases were placed in the hands of federal commissioners, who received a higher fee—ten dollars—if they ruled in favor of the claimant, and only five dollars if they freed the accused. The law also compelled all citizens, regardless of personal conviction, to assist in the capture of fugitives when called upon. Failure to comply risked heavy fines and imprisonment.

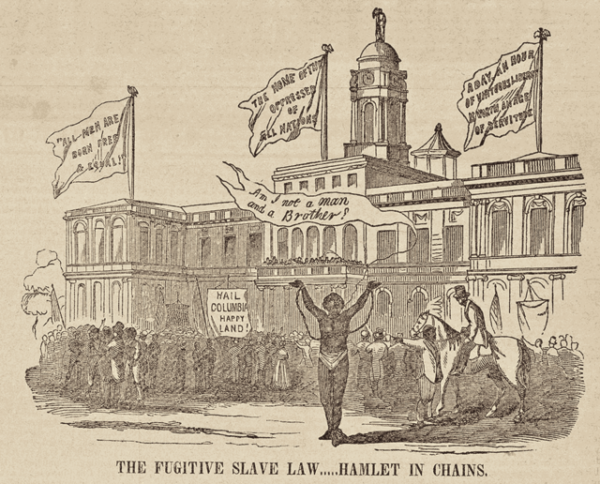

For abolitionists, the law was a nightmare. It threatened free Black communities in the North, since kidnappers could easily accuse individuals of being runaways and haul them south with little recourse. Famous cases, such as those of Shadrach Minkins in Boston and Anthony Burns a few years later, dramatized the brutal enforcement of the act and galvanized resistance. In city after city, antislavery activists organized vigilance committees, sheltered fugitives, and sometimes resorted to violent rescues. Ministers thundered from pulpits that obedience to such a law was obedience to sin.

Northern moderates, too, were shaken. Many who had previously tolerated slavery as a distant Southern institution now confronted its presence in their own communities. The sight of federal marshals dragging men, women, and even children through northern streets under military guard appalled citizens who had thought slavery would never touch their lives directly. The act thus radicalized northern opinion and gave the abolitionist cause new converts.

In the South, however, the Fugitive Slave Act was regarded as an essential safeguard. Slaveholders saw it as a test of northern good faith: if free states refused to enforce the return of fugitives, then the Union itself stood on shaky ground. Yet even with the law in place, southern discontent persisted. Many believed the North’s widespread defiance proved that their rights could never be secure within the Union.

Politically, the law was disastrous for compromise. It became a rallying cry for the newly formed Republican Party in the mid-1850s, which denounced the expansion of slavery and its encroachment on northern liberties. Abraham Lincoln himself would point to the Fugitive Slave Act as evidence of a “slave power” conspiracy dominating the federal government.