On the gray morning in occupied New York City, a 21-year-old Connecticut schoolteacher turned Continental officer met his end at the hands of the British. Nathan Hale, captured while attempting to gather intelligence behind enemy lines, was hanged as a spy on September 22, 1776—an event that has since entered the canon of American Revolutionary lore, bound up with the enduring words attributed to him: “I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country.”

The story of Hale’s final hours is inseparable from the desperate circumstances of the Continental Army. In the late summer of 1776, George Washington’s troops had suffered a crushing defeat at the Battle of Long Island. British forces under General William Howe pressed their advantage, occupying New York City and threatening to strike across the East River into the very heart of Washington’s lines. Washington urgently needed intelligence on British movements, particularly their fortifications on Manhattan and Long Island. To gather that information, he turned to the commander of his elite light infantry regiment, Thomas Knowlton, who called for volunteers. Nathan Hale, a Yale-educated officer with little battlefield experience, stepped forward.

Disguised as a Dutch schoolmaster, Hale crossed into enemy-controlled territory in early September. He reportedly moved through Long Island and New York, taking notes on British positions. But his mission was quickly compromised. Accounts differ as to whether Loyalist informants exposed him, or whether he was recognized by Major Robert Rogers of the Queen’s Rangers, a notorious Tory commander. What is clear is that Hale was apprehended, his incriminating papers hidden poorly in his shoes, and brought before British officers.

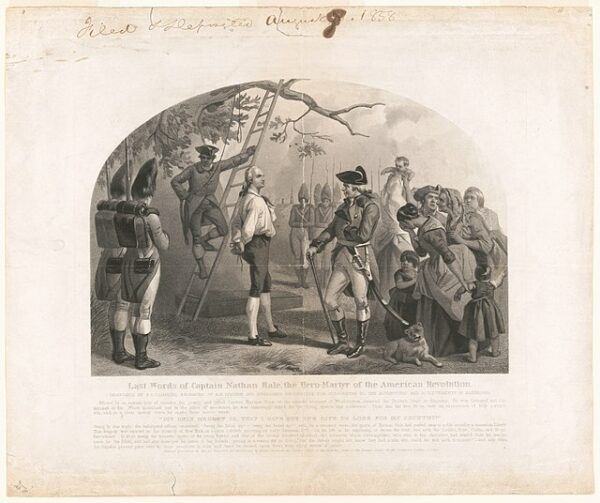

In the law of war, a captured spy was afforded no mercy. Unlike a prisoner of battle, who could expect parole or exchange, the fate of a spy was swift execution. General Howe signed Hale’s death warrant without convening a formal trial. On the morning of September 22, Hale was marched to the gallows near what is today 66th Street and First Avenue in Manhattan. Eyewitnesses recalled him comporting himself with unusual composure for so young a man. British officer Frederick MacKenzie noted that Hale “behaved with great composure and resolution.” Another account recorded that he declared himself satisfied with his conduct and regretted only that he had but one life to lose in the cause of liberty.

Historians have long debated the exact phrasing of his final words. The most famous version, immortalized in American memory, comes from a postwar account by William Hull, a fellow officer who claimed to have heard Hale’s declaration secondhand. Critics have suggested that Hale’s farewell may have been shaped by later patriotic retelling, echoing lines from Joseph Addison’s popular play Cato, which Revolutionary soldiers knew well. Yet whether perfectly accurate or not, the sentiment embodied in those words captured the spirit of sacrifice that the struggling Continental Army needed in its darkest days.

Hale’s death had little immediate effect on the outcome of the New York campaign. Within days, Washington’s army retreated northward, narrowly avoiding destruction. Yet his execution became a symbol of the war itself: the young, educated patriot who gave his life not for glory but for principle. In a conflict often marked by desertion, opportunism, and brutal pragmatism, Hale’s willingness to face the hangman’s noose offered a moral counterpoint.

Over time, his memory was enshrined in stone and verse. Statues of Hale stand today outside Yale University, the CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia, and New York’s City Hall Park. His face, resolute and youthful, became a reminder that the struggle for independence demanded more than speeches and declarations; it required lives freely given. Even British observers conceded his courage. One report in a Loyalist newspaper noted that “his dying speech was worthy of the cause for which he suffered.”

On that September morning, the American Revolution was still an uncertain enterprise, with the rebellion battered and its prospects dim. Hale’s sacrifice, insignificant in strategic terms, was transformative in symbolic weight. He died alone, without uniform, without trial, condemned as a criminal by the greatest empire of the age. But his words—real or remembered—ensured that his death would not vanish into obscurity. They gave a fledgling nation a martyr whose legacy still speaks across the centuries.