President Dwight D. Eisenhower took the extraordinary step of ordering federal troops into Little Rock, Arkansas, today, deploying the 101st Airborne Division to enforce desegregation at Central High School. The move marked one of the most dramatic assertions of federal authority over states’ rights since Reconstruction and placed the prestige of the presidency squarely behind the Supreme Court’s ruling in Brown v. Board of Education.

The crisis had been mounting for weeks. In early September, nine Black students—soon to be known as the “Little Rock Nine”—attempted to integrate Central High under a federal court order. Their arrival was met with a hostile white crowd and the Arkansas National Guard, whom Governor Orval Faubus had ordered to block their entry. Faubus claimed his actions were necessary to preserve peace, but to civil rights advocates his defiance represented nothing less than open rebellion against constitutional law.

On September 20, a federal judge directed Faubus to withdraw the Guard, but their departure left the students even more exposed. When the nine teenagers tried again to enter the school on September 23, they were met by a mob of nearly a thousand, hurling insults, spitting, and threatening violence. Local police struggled to control the crowd, and by day’s end the children were spirited away for their own safety. The spectacle of American citizens being denied education under armed intimidation reverberated across the world—a dangerous embarrassment in the midst of the Cold War, when Washington claimed to lead the free world.

Eisenhower, reluctant by temperament and conviction to involve the federal government in racial disputes, was pushed to act. In a nationally televised address on the evening of September 24, he explained his decision. “Mob rule cannot be allowed to override the decisions of our courts,” he declared. He described the events in Little Rock as a “disorderly mob” obstructing justice and undermining the authority of the United States. To Eisenhower, the crisis was not merely a Southern problem but a direct challenge to the rule of law.

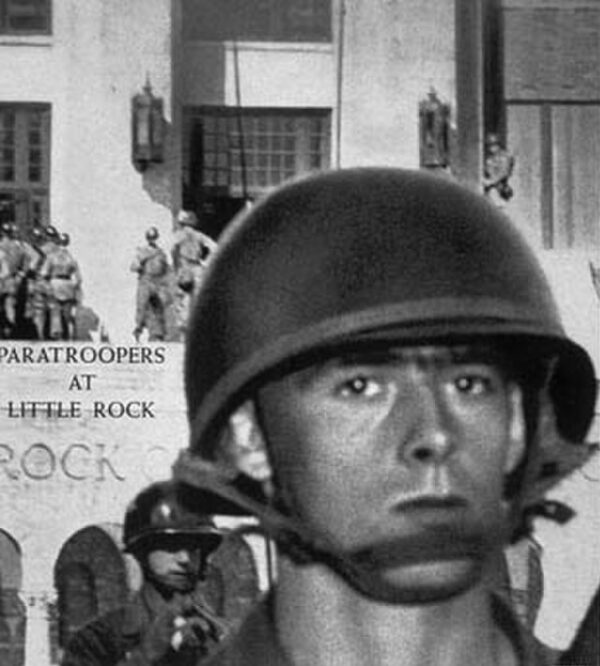

Within hours, the 101st Airborne—the same division that had parachuted into Normandy—landed at Little Rock Air Force Base. Soldiers equipped with bayonets and jeeps rolled into the city, taking up positions around Central High. Eisenhower also federalized the Arkansas National Guard, stripping Faubus of his control. On September 25, under the protection of paratroopers, the nine students entered the school through a side door. This time they stayed, their presence symbolizing both the fragility and resilience of desegregation.

The images were stark: young children escorted to class by soldiers, troops patrolling hallways, and barbed wire stretched across the lawns of an American high school. For critics, it was a chilling portrait of federal power trampling local autonomy. For supporters, it was the long-overdue enforcement of constitutional equality. The students themselves bore the brunt. Inside the school they faced relentless harassment, verbal abuse, and physical threats from white classmates. Yet their perseverance became emblematic of the broader civil rights struggle.

The Little Rock crisis underscored the gap between law and practice in the South. The Supreme Court had spoken in 1954, declaring segregated schools unconstitutional, but three years later only token progress had been made. Many white Southerners clung to “massive resistance,” enacting legislation to delay or nullify integration. Faubus’s defiance was the most visible—and, after Eisenhower’s intervention, the most costly—episode of that strategy.

Internationally, the deployment of troops sent a message as well. Soviet propagandists had seized upon the images of mobs attacking schoolchildren as evidence of American hypocrisy. Eisenhower, a former general keenly aware of the battle for global opinion, sought to reassert U.S. credibility by showing that federal authority would not be mocked. Domestically, however, the decision split his party. Some Republicans applauded his defense of law and order; others warned of alienating Southern whites who increasingly leaned toward the GOP.

In the long view, Eisenhower’s intervention set a precedent. It demonstrated that federal power could and would be used to enforce civil rights rulings, even in the face of massive local opposition. The courage of the Little Rock Nine, coupled with the weight of federal arms, pushed the civil rights struggle into a new phase.