On October 3, South Korea marks one of its most venerable observances—Gaecheonjeol (개천절), the “Day the Heavens Opened.” According to tradition, the origins of the Korean nation trace back not merely to migrations or dynastic shifts, but to the descent of a celestial being. In 2457 BC, so the myth tells, Hwanung (환웅), son of the heavenly ruler Hwanin, came down to earth to govern humanity and establish a just order. His arrival, recorded in the Samguk Yusa (Memorabilia of the Three Kingdoms) centuries later, forms the mythical cornerstone of Korea’s national identity.

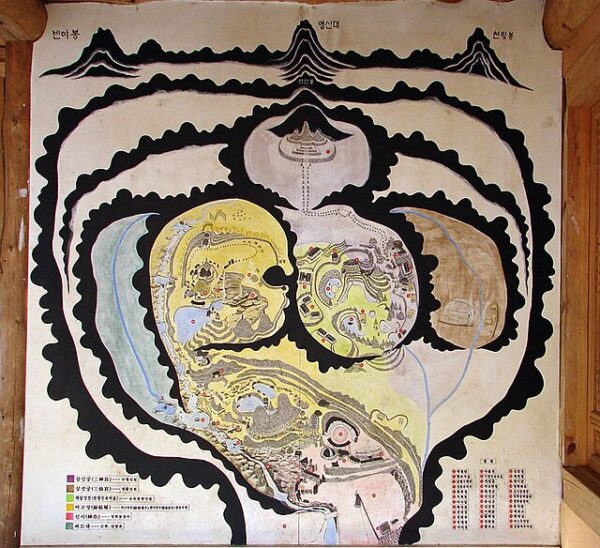

The legend is layered with cosmological grandeur. Hwanin, lord of heaven, saw in his son Hwanung a ruler fit not for the skies but for the human realm. With three thousand followers, Hwanung descended through Mount Taebaek, settling beneath a sacred tree at a place called Sindansu. There he founded a heavenly city-state and created institutions governing agriculture, medicine, law, and morality. In this mythic scheme, politics and providence intertwined; governance was not an invention of man but a divine bequest.

It was within this realm that the story of Korea’s progenitor unfolded. A bear and a tiger sought to become human and prayed to Hwanung for transformation. He decreed that they endure one hundred days in darkness, subsisting only on garlic and mugwort. The tiger failed, but the bear endured, emerging as a woman, Ungnyeo. She later bore a child by Hwanung, and that son—Dangun Wanggeom—became the founder of the first Korean kingdom, Gojoseon. Thus the lineage of a people, their first state, and their cosmology were all woven into one mythical genealogy.

For modern Koreans, October 3 is not simply a quaint echo of legend but a civic holiday, National Foundation Day. Established in the early twentieth century during the ferment of nationalist resistance, the holiday was meant to root the Korean nation in antiquity, giving it a dignity equal to other ancient civilizations. Under Japanese occupation, intellectuals seized upon the Dangun myth to assert that Korea had an indigenous origin story, one that antedated Chinese dynasties or colonial narratives. In that sense, Gaecheonjeol became a subtle act of defiance, a reminder that Korea’s sovereignty had celestial sanction.

Today, ceremonies across South Korea mark the date with solemnity. At the Dangun Shrine on Mount Mani in Ganghwa Island, rituals of remembrance unfold, invoking the founder’s spirit and the heavenly descent. The South Korean president delivers a commemorative address, drawing on the myth to frame national unity and resilience. For many citizens, the day serves not only as a historical marker but as a reminder of Korea’s endurance—through colonization, war, and division.

Historians and anthropologists often note that Gaecheonjeol reveals as much about the present as the past. The myth itself may not be a literal record of 2457 BC, but it operates as a cultural charter. By claiming divine descent, Koreans affirmed their place among ancient civilizations. By commemorating it annually, they reinforce a sense of continuity that bridges millennia. In an era of rapid modernization, globalization, and shifting geopolitical pressures, the holiday roots the nation in something timeless.

At the same time, the narrative of Hwanung and Dangun contains universal themes. It is a story of transformation—the bear becoming human through endurance, the divine mingling with the mortal, the chaotic world ordered by law and ritual. It echoes other foundation myths, from Romulus and Remus in Rome to the Mandate of Heaven in China. Yet its distinctively Korean character lies in its fusion of natural and spiritual elements: mountains, trees, animals, and gods entwined in the making of a nation.

Critics might argue that modern states should not rely on myths for legitimacy. Yet myths, whether Greek, Roman, or Korean, function less as factual accounts than as vessels of meaning. Gaecheonjeol embodies ideals of perseverance, justice, and divine mandate. It tells Koreans that their origins are not accidental but purposeful, that their history is framed not by conquest but by descent from heaven itself.

Thus, when South Koreans gather on October 3, they do more than mark an anniversary. They participate in a tradition that stretches back to the imagined dawn of their people, one that endows their modern republic with an ancient soul. The heavens, they are told, once opened for Korea. Each year, Gaecheonjeol reopens them, however briefly, to remind a divided peninsula of its common origin.