By the autumn of 1877, the Nez Perce War had become one of the most remarkable and tragic episodes in the long struggle between Native peoples and the expanding United States. What began that June as a desperate flight to preserve tribal freedom ended four months later on a frigid Montana plain, when Chief Joseph—exhausted, starving, and encircled—surrendered his band to the U.S. Army on October 5, 1877.

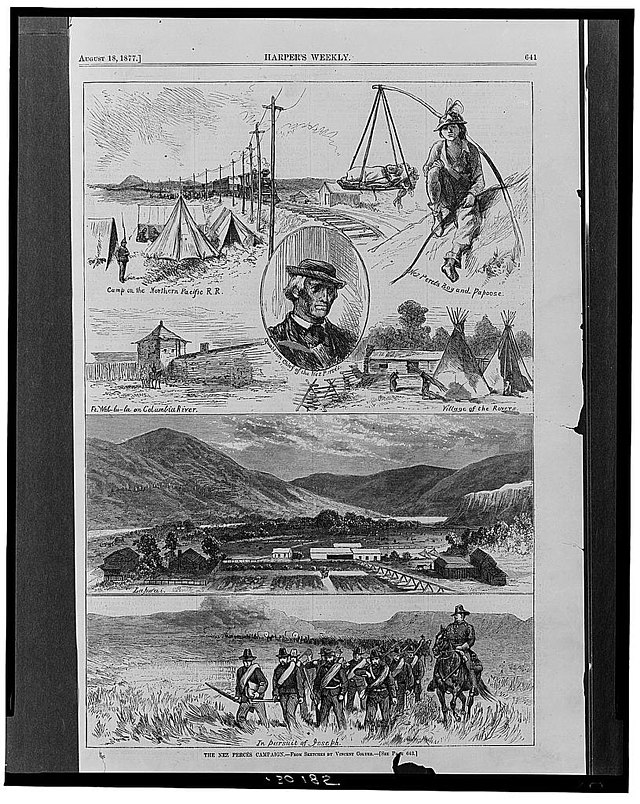

The conflict’s origins lay in the U.S. government’s determination to confine the Nez Perce to a reservation in Idaho. The 1855 treaty had guaranteed them 7.5 million acres across the Wallowa Valley of present-day Oregon, but gold discoveries and settler incursions shrank that territory by nearly 90 percent in a later 1863 “steal treaty.” Chief Joseph’s father refused to sign it, and his band continued to live freely in their ancestral valley for another decade—until federal orders in 1877 demanded their removal. When tensions flared and a group of young Nez Perce warriors killed several white settlers, the U.S. Army—under General Oliver O. Howard—launched a punitive campaign. What followed was less a conventional war than a 1,400-mile running flight: roughly 750 Nez Perce men, women, and children, with fewer than 200 fighters, evaded and battled some 2,000 pursuing soldiers across Idaho, Wyoming, and Montana.

The campaign astonished observers for its scale and skill. The Nez Perce fought rearguard actions at White Bird Canyon, the Clearwater, and the Big Hole, and crossed the Continental Divide twice. Pursuing troops often praised their discipline and courage. Colonel John Gibbon, one of their adversaries, later called them “the finest light cavalry in the world.” Guided by tribal scouts and their own intimate knowledge of the terrain, they eluded capture for months, seeking refuge with the Crow and, when rebuffed, turning north toward Canada and the protection of Sitting Bull’s Lakota—barely forty miles beyond the Bear Paw Mountains when the U.S. Army caught them.

On October 5, after a five-day siege in freezing sleet, only about 87 Nez Perce warriors remained capable of fighting. Many of their families had perished or been captured. Chief Joseph, realizing further resistance meant annihilation, met with General Nelson A. Miles and uttered words that would echo through history:

“Tell General Howard I know his heart. What he told me before, I have it in my heart. I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are killed; Looking Glass is dead; Toohoolhoolzote is dead. The old men are all dead. It is the young men who say yes or no. He who led on the young men is dead. It is cold, and we have no blankets. The little children are freezing to death. My people—some of them—have run away to the hills and have no blankets, no food. No one knows where they are—perhaps freezing to death. I want to have time to look for my children and see how many of them I can find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my chiefs! I am tired; my heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever.”

The speech—its precise phrasing likely embellished by army interpreters—nonetheless captured the exhaustion and dignity of a leader facing defeat with humanity intact. Despite promises that the survivors could return to Idaho, the government instead transported them to prison camps in Kansas and then to Indian Territory, where disease claimed many lives. Not until 1885 were the remaining Nez Perce allowed to move to the Pacific Northwest—though not to their beloved Wallowa Valley. Chief Joseph himself spent his final years pleading for that right, dying in 1904 still far from home.

The Nez Perce War lasted only a season, yet it left an enduring moral imprint on the American conscience. Historians see it as the last large-scale Indian war in the Pacific Northwest and one of the most eloquent protests against the breaking of treaties. The Nez Perce fought not for conquest but for the freedom to live according to their traditions on their ancestral land. When Joseph surrendered on that cold October day in 1877, the frontier’s military conquest was nearly complete. But his words—and the vision of a people who fled across mountains rather than surrender their identity—remained a rebuke to the nation’s triumphal story.