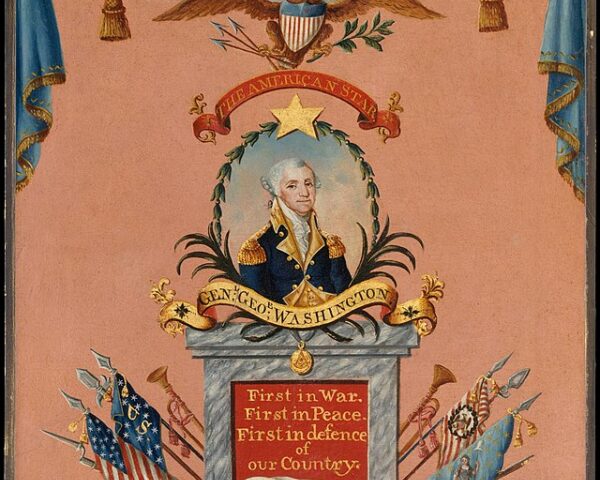

workmen laid the cornerstone of the United States Executive Mansion—an act marking the symbolic birth of what would later become known as the White House. The event unfolded amid the fields and forests of a fledgling federal city that existed mostly on paper, a vision of President George Washington and his appointed planner, Pierre Charles L’Enfant. Though the capital was still little more than a clearing surrounded by swamps, the ceremony represented the physical foundation of a new nation’s seat of power.

The site chosen for the mansion lay slightly northwest of the future Capitol, on high ground with a view toward the Potomac. The structure was intended not as a palace but as a home suitable for a republican leader—a conscious rejection of European monarchical grandeur. Its architect, James Hoban, an Irish immigrant who had studied in Dublin, won a design competition earlier that year. His neoclassical plan, inspired by Leinster House in Dublin and the symmetry of Palladian forms, balanced elegance with restraint, embodying the modest dignity Washington wished to convey.

Washington himself presided over the cornerstone ceremony, joined by local masons, laborers, and government officials. True to his Masonic affiliation, he participated in the ritual laying of the stone, reportedly placing a silver plate beneath it inscribed with the date and the names of key figures in the new Republic. Though no contemporary newspaper account of the ceremony survives, tradition holds that the event included prayers, processions, and the firing of cannon salutes. It was a moment of high symbolism: the physical expression of the young nation’s endurance and faith in its constitutional experiment.

The project faced immense challenges from the outset. The capital itself—named for Washington but situated between Maryland and Virginia—was little more than a construction site plagued by heat, disease, and shortages of skilled labor. Workers included both free men and enslaved Africans hired out by local owners, whose toil under brutal conditions helped raise the limestone walls that still stand today. Hoban oversaw a workforce of stonemasons, carpenters, and artisans from across the mid-Atlantic region, their combined effort slowly giving shape to the building that would serve as the residence of every American president after John Adams.

Construction proceeded fitfully over the next eight years, hindered by limited funding and the remote location. The structure’s sandstone exterior, quarried from Aquia Creek in Virginia, was left porous and later coated with white lead paint—giving rise to the nickname “White House,” which entered common usage by 1818. Inside, the mansion’s rooms were austere but stately, meant to balance private domestic life with the demands of diplomacy and ceremony. Adams moved in on November 1, 1800, writing to his wife Abigail that he prayed “none but honest and wise men ever rule under this roof.”

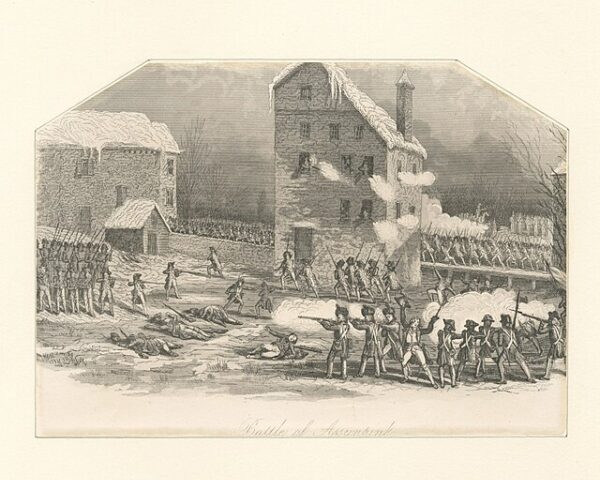

The Executive Mansion would endure fire, war, and political turmoil, yet remain the enduring symbol of the American presidency. During the War of 1812, British troops torched the building, leaving its blackened shell standing as a national humiliation. Yet it was rebuilt almost immediately, again under Hoban’s supervision, with greater ornamentation and renewed determination—a physical testament to the republic’s resilience. Over time, each administration would leave its mark: Jefferson’s colonnades, Monroe’s French furnishings, Truman’s structural overhaul, and Kennedy’s restoration of historical elegance.

Today, the White House remains not merely an address but an emblem—a living monument to the endurance of the constitutional order begun in 1789.