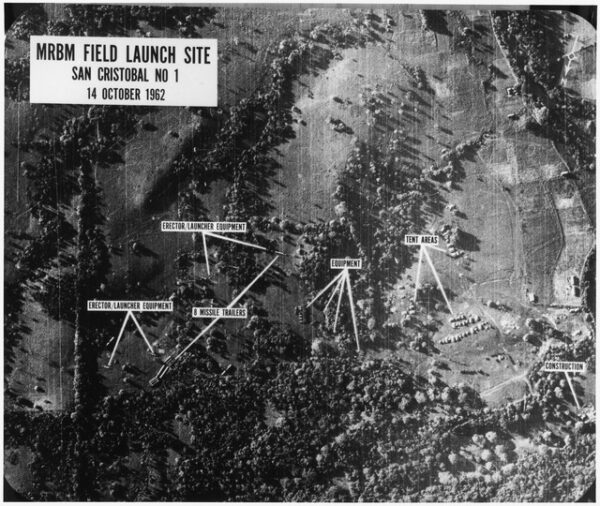

On October 16, 1962, President John F. Kennedy received the news that would bring the world closer to nuclear war than ever before. Two days earlier, on October 14, an American U-2 reconnaissance plane flying over western Cuba had captured a series of high-resolution photographs revealing what U.S. intelligence analysts now confirmed: the Soviet Union was secretly constructing medium- and intermediate-range ballistic missile sites on the island, capable of launching nuclear warheads toward major American cities within minutes. The discovery set in motion thirteen days of escalating tension, strategic calculation, and brinkmanship known to history as the Cuban Missile Crisis.

When the photographs reached Washington, they were first examined at the National Photographic Interpretation Center (NPIC), where analysts quickly identified telltale features—missile erector launchers, fuel trucks, and long, cylindrical objects consistent with Soviet R-12 and R-14 nuclear missiles. The implications were staggering. Since Fidel Castro’s 1959 revolution, the U.S. had tolerated the existence of a communist regime ninety miles from Florida, but the introduction of offensive nuclear weapons crossed an unspoken line. The missiles directly threatened the continental United States for the first time, nullifying the strategic advantage America held through its Jupiter missiles stationed in Turkey and Italy.

At 8:45 a.m. on October 16, Kennedy convened his senior advisers in the Cabinet Room for what would become the first meeting of the Executive Committee of the National Security Council, or ExComm. Present were Vice President Lyndon Johnson, Defense Secretary Robert McNamara, CIA Director John McCone, Secretary of State Dean Rusk, National Security Adviser McGeorge Bundy, and several key military and diplomatic officials. As the photographs were passed around the table, Kennedy listened quietly, probing for clarity. McCone explained the range and capabilities of the missiles; McNamara emphasized the limited window before they became operational. Within a matter of days, the crisis had transformed from a technical intelligence issue into the most perilous confrontation of the Cold War.

Kennedy’s advisers were divided on how to respond. The Joint Chiefs of Staff, led by Air Force General Curtis LeMay, urged an immediate air strike to destroy the missile sites, followed by an invasion of Cuba to eliminate the Castro regime entirely. LeMay compared Kennedy’s hesitation to the appeasement of Hitler at Munich. Civilian advisers, including McNamara and Robert Kennedy, cautioned against precipitous action, warning that such an attack could trigger a Soviet response in Berlin or even a full-scale nuclear exchange. “If we attack Cuba,” the president’s brother argued, “then we should be prepared for nuclear war.”

Over the next two days, the president weighed options in secrecy. Kennedy ruled out an immediate strike, choosing instead a naval “quarantine” to prevent further Soviet shipments of missiles and military supplies to Cuba. On October 22, he addressed the nation in a televised speech that electrified the world. Revealing the presence of Soviet nuclear missiles in Cuba, Kennedy announced the quarantine and warned that any launch from Cuba would be met with “a full retaliatory response upon the Soviet Union.” The crisis had become public, and the clock toward potential Armageddon began ticking.

As Soviet ships steamed toward the U.S. blockade line in the Atlantic, the standoff entered a nerve-shattering phase. American forces were placed at DEFCON 2—the highest state of readiness short of nuclear war. Strategic bombers armed with hydrogen bombs circled the Arctic. Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, confronted by Kennedy’s resolve and the prospect of mutual annihilation, ultimately relented. After tense backchannel negotiations, a deal was struck: the Soviets would dismantle their Cuban missiles under United Nations supervision, and in exchange the United States pledged not to invade Cuba and quietly agreed to remove its Jupiter missiles from Turkey.

By October 28, the crisis was over. Both leaders had pulled back from the brink, establishing a direct “hotline” between Washington and Moscow to prevent future miscalculations. The Cuban Missile Crisis became the defining moment of the nuclear age—a confrontation that demonstrated both the fragility of peace and the prudence of restraint. For Kennedy, it was a victory of measured resolve over military aggression; for the world, it was a narrow escape from catastrophe.