On October 23, 2001, Apple Computer unveiled a pocket-sized device that would redefine the way the world listened to music. Weighing just 6.5 ounces and small enough to slip into a jeans pocket, the iPod promised “a thousand songs in your pocket.” Few outside Apple’s Cupertino campus grasped that this white-plastic rectangle—priced at $399—would do more than upend the CD player. It would transform the entire music industry and rescue Apple itself from the margins of consumer electronics.

When Steve Jobs took the stage in Apple’s Town Hall auditorium, the company was still recovering from years of financial uncertainty. The colorful iMac had restored some luster to the brand, but Apple remained a niche computer maker. The digital-music world, meanwhile, was chaotic—dominated by clunky MP3 players, illegal Napster downloads, and record labels struggling to contain piracy. Jobs saw opportunity where others saw disorder. “Listening to music will never be the same again,” he declared, holding up the first iPod between thumb and forefinger.

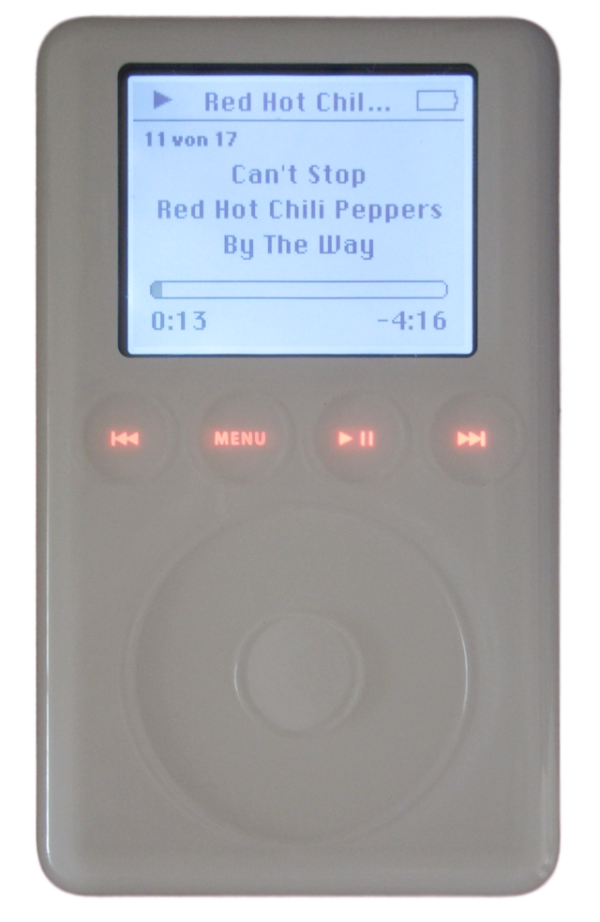

The iPod’s breakthrough lay in its simplicity. Instead of forcing users to drag and drop individual tracks, it synchronized automatically with iTunes, Apple’s new desktop software. Songs ripped from CDs could be imported, organized, and transferred in minutes. Its 5-gigabyte hard drive—made by Toshiba and about the size of a quarter—could store roughly one thousand CD-quality songs. A mechanical scroll wheel let users zip through tracks with tactile ease, while the monochrome LCD displayed crisp menus that echoed Apple’s minimalist design philosophy. The company’s engineers had squeezed cutting-edge technology into a case barely three-quarters of an inch thick.

Critics, however, scoffed. Why would anyone spend $399 on an MP3 player when cheaper ones already existed? And it was Mac-only, a limitation that initially excluded the vast majority of computer users. Some analysts dismissed it as a stylish toy for Apple loyalists. But early adopters raved about the device’s intuitive interface, fast FireWire transfers, and long battery life. The iPod’s elegance turned heads wherever it appeared—an aesthetic extension of Jobs’s obsession with seamless design.

Within months, demand exceeded expectations. In 2002 Apple introduced a Windows-compatible version, shattering the Mac-only barrier and sending sales soaring. By 2003, Apple had sold nearly a million units, aided by the launch of the iTunes Music Store, which offered 99-cent song downloads in partnership with major labels. Legal digital music finally had a business model. “People want to own their music,” Jobs told reporters. “They just want an easy, honest way to get it.”

The cultural impact was immediate. White earbuds became a status symbol, visible on subway commutes, jogging trails, and college campuses. The iPod advertising campaign—silhouetted dancers grooving against bright neon backgrounds—captured a generation’s optimism at the dawn of the digital century. Music consumption shifted from albums to playlists, from passive listening to personal curation. The phrase “shuffle your songs” entered everyday speech. Even competitors who once mocked Apple scrambled to emulate its formula.

Behind the scenes, the iPod became Apple’s financial engine. Annual revenue leapt from $5.3 billion in 2001 to $14 billion by 2005. The profits funded a wave of innovation that would culminate in the iPhone six years later. Engineers who cut their teeth miniaturizing hard drives and refining the click wheel later helped design multi-touch screens and mobile operating systems. The iPod, in retrospect, was not just a product—it was Apple’s bridge from the desktop to the pocket.

The line expanded rapidly: the iPod Mini in 2004, the Nano in 2005, the screen-less Shuffle in 2005, and the video-capable iPod Classic in 2007. At its peak, Apple sold more than 50 million iPods a year, dominating more than 70 percent of the portable-music market. Entire ecosystems of accessories, from speaker docks to car adapters, sprang up around it. Record stores vanished, replaced by digital libraries. The Walkman, once the symbol of portable sound, faded into nostalgia.