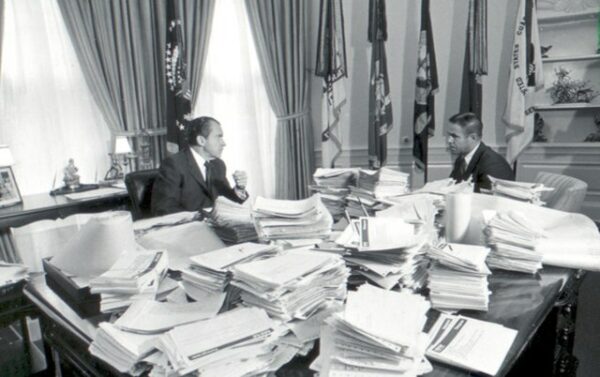

On the evening of November 3, 1969, President Richard M. Nixon delivered one of the most consequential speeches of his presidency—a direct appeal to what he famously called the “silent majority” of Americans. Speaking live from the Oval Office, Nixon sought to rally public support for his Vietnam War policies at a time when the nation was deeply divided and the antiwar movement was reaching its height. His calm, measured tone masked the gravity of the political moment. Behind the words lay a stark question: would the American public continue to stand behind the long and costly war in Southeast Asia, or would it demand immediate withdrawal and risk what Nixon warned would be a humiliating defeat?

By late 1969, U.S. involvement in Vietnam had stretched on for nearly a decade, with over 500,000 American troops deployed and tens of thousands killed. Nixon, who had taken office that January, inherited a conflict that had become both a military stalemate and a moral crisis. He introduced a strategy he called “Vietnamization”—a gradual process of turning combat responsibilities over to the South Vietnamese army while steadily withdrawing U.S. forces. Yet many Americans, weary of years of broken promises from Washington, doubted his sincerity or the strategy’s viability. Protests erupted on college campuses and in city streets, with demonstrators demanding an immediate end to the war. Nixon’s speech that November was his attempt to seize back the political initiative.

“I have chosen a plan for peace. I believe it will succeed,” Nixon told the nation. “And I believe that the American people will support me in this difficult decision.” He framed his argument not as one of aggression, but of endurance—an appeal to the nation’s sense of resolve and unity. “And so tonight—to you, the great silent majority of my fellow Americans—I ask for your support.” The phrase struck an immediate chord. With those few words, Nixon gave a name and a voice to millions of citizens who were neither activists nor demonstrators, who believed in patriotism, order, and the legitimacy of the war’s aims, even if they disliked its costs.

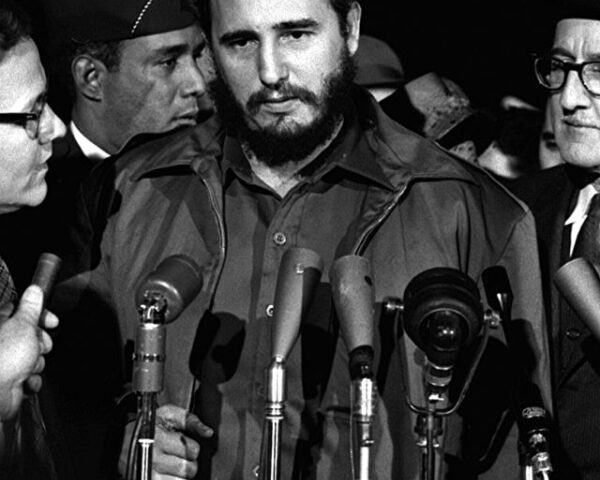

The address was as much a domestic strategy as a foreign-policy statement. Nixon’s aides, including speechwriter Patrick Buchanan and Vice President Spiro Agnew, had urged him to confront the growing antiwar movement head-on. They believed that a vast segment of the public—working- and middle-class Americans in particular—felt alienated by what they saw as elite protest culture. Nixon’s rhetorical genius lay in framing support for his policy not as blind nationalism but as a defense of American credibility and global leadership. He portrayed the war as part of the larger Cold War struggle against communist expansion, warning that “if we betray our allies, we will encourage future aggression” from adversaries like the Soviet Union and China.

The reaction was immediate and polarizing. Polls showed that nearly 77 percent of Americans approved of the speech and Nixon’s handling of the war. Letters poured into the White House—thousands each week—mostly from citizens expressing gratitude for what they saw as a restoration of moral clarity and presidential authority. Yet among critics, the phrase “silent majority” became a symbol of division. Antiwar activists argued that Nixon was weaponizing public sentiment to stifle dissent, painting protesters as unpatriotic rather than principled. Senator George McGovern called the address “a political maneuver designed to justify a policy of endless war,” while The New York Times editorial board accused Nixon of “hiding behind rhetoric to mask the absence of a clear exit strategy.”

Nevertheless, the Silent Majority Speech marked a decisive political victory for Nixon. It helped shore up his base, quieted congressional calls for an immediate pullout, and set the tone for his administration’s broader campaign to reclaim the cultural center. The term “silent majority” itself would echo for decades, invoked by politicians across the spectrum to signal solidarity with ordinary Americans who felt overlooked by elites or activists.

In retrospect, the speech was both an act of persuasion and a reflection of Nixon’s deep political instincts. It revealed his understanding of America’s social fault lines—between those who protested and those who worked quietly, between the young and the old, between faith in government and disillusionment with it. While the war dragged on for another four years, Nixon’s appeal that night helped define the political realignment of the late 20th century, ushering in an era where appeals to the “silent majority” would become a defining feature of American populism.