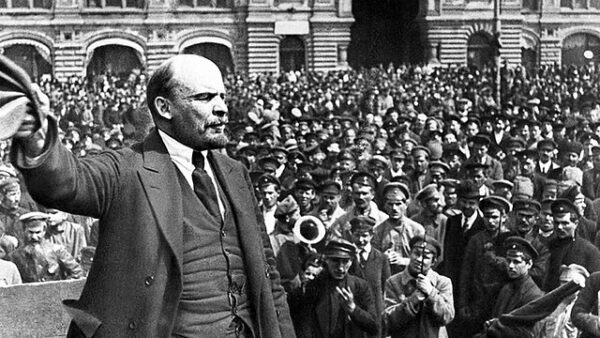

On November 5, 1917 (New Style; October 23 by Russia’s Old Style calendar), Vladimir Lenin pressed his case for an immediate armed uprising, transforming months of revolutionary agitation into a concrete timetable. Bolshevik power in Petrograd had grown rapidly since the summer: factory committees were increasingly radical, the garrison was unreliable for the Provisional Government, and the Petrograd Soviet—now chaired by Lev Trotsky—had established a Military Revolutionary Committee (MRC) that effectively served as a parallel authority. Yet the final leap from dual power to singular power still required a decision. Lenin insisted the window was open and narrowing. War weariness and bread shortages had made the city volatile; the government under Alexander Kerensky was brittle but not yet broken; and moderate socialists still believed they could stitch together a parliamentary path. Lenin, in hiding and writing under disguises, argued that hesitation was counterrevolutionary in practice. November 5 became the day he shifted from advocacy to insistence.

The MRC had already begun issuing orders, testing loyalties, and mapping critical nodes: telegraph, rail terminals, bridges, the State Bank, and the post office. Trotsky’s genius for organization gave Lenin’s urgency a chassis. Regimental committees were quietly told to answer to the Soviet rather than the War Ministry; Red Guards received munitions and instructions; couriers ran between district soviets and Smolny Institute, the Bolshevik headquarters. What Lenin demanded on November 5 was simple in phrasing and radical in effect: set the clock. In memoranda and messages to the Central Committee—echoing his earlier “Marxism and Insurrection” arguments—he warned that political capital decays like bread on a windowsill. If they waited for the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets to confer legitimacy before acting, the Provisional Government would disperse the Congress or tighten the city’s arteries. If they struck first, the Congress could ratify the new reality.

Kerensky, sensing danger, tried to reshuffle commanders and move loyal units toward the capital. But his capacity to act was compromised by two facts that November 5 laid bare. First, “loyal” meant less than it used to: soldiers voted with their feet, and their rifles, and many feet drifted toward the Soviet. Second, paper decrees traveled by wire and rail the Bolsheviks increasingly controlled. Every hour the MRC tightened administrative grip—often under the color of defending the revolution from an imagined “Kornilovite” plot—was an hour the Provisional Government lost the ability to maneuver.

Lenin’s critics on the Left urged patience. Why trade a broad socialist coalition for a party-led seizure that risked civil war? Because, Lenin answered, the state’s shell was already empty. The bourgeois center could not end the war or feed the cities; peasant seizures in the countryside were outpacing legislation; and any “coalition” would only repackage paralysis. The revolutionary moment, as he framed it, was not a romantic instant but a mathematical interval: given sufficient soviet majorities in Petrograd and Moscow, the presence of armed workers and sympathetic soldiers, and a government that could neither command nor provision, the probability of success peaked—now.

So November 5 functioned like the drumroll before the overture. The MRC posted commissars to strategic units and buildings under the legal pretext of “defense.” Printing presses ran off proclamations warning against counterrevolution and asserting that all orders must carry the Soviet’s signature. Armed detachments rehearsed routes across the city’s bridges. Smolny hummed with maps, passwords, and timetables. Lenin—still disguised, still impatient—pressed the Central Committee to approve the insurrection’s operational plan and to synchronize it with the opening of the Congress of Soviets, ensuring that revolutionary force and revolutionary legitimacy would meet on stage together.

Two days later, on November 7 (October 25 O.S.), the plan unfolded with startling efficiency: key junctions passed into Bolshevik hands, the cruiser Aurora signaled the assault on the Winter Palace, and the Provisional Government dissolved in a burst of confusion and sporadic gunfire. But the hinge of the door was November 5. That day consolidated will, aligned the party with the MRC’s machinery, and translated abstract “dual power” into a countdown. In the history of revolutions, there are many speeches and fewer clocks. Lenin’s November 5 call set a clock—and once it started, Petrograd’s old order had almost no time left.