Thirteen minutes. On the night of November 8, 1939, while Munich’s old Bürgerbräukeller echoed with the loyalist cheers of Nazi Party faithful commemorating the sixteenth anniversary of the Beer Hall Putsch, Adolf Hitler slipped out of the hall thirteen minutes earlier than scheduled—a minor adjustment in a dictator’s choreographed routine that saved his life. At 9:20 p.m., a homemade bomb planted by a quiet, unassuming Swabian carpenter named Georg Elser detonated beneath the speakers’ platform where Hitler had just delivered his annual speech. The blast tore through the stone pillars, collapsed the ceiling, killed eight, and injured more than sixty. Hitler was already on a train racing back to Berlin to coordinate war plans.

Elser had spent the better part of a year constructing the conditions for that moment. Working alone, refusing all co-conspirators and all contacts, he entered the Bürgerbräukeller night after night posing as a patron, quietly studying guard rotations, the structure of the hall, and the timing of Hitler’s speeches. Beginning in August 1939, he snuck in after closing hours—sometimes hiding in a storage closet until staff departed—and hollowed out a cavity in one of the pillars supporting the speaker’s platform. Using stolen explosives from a quarry where he had once worked, he engineered a time-delay mechanism of remarkable precision: two clocks, wired in parallel, set to trigger at the exact minute Hitler was expected to be mid-oration.

The dictator’s schedule, however, shifted. With the war against Britain and France underway, Hitler insisted on returning to Berlin early to meet with military chiefs. His speech was shorter; he left abruptly. And so Elser’s bomb, perfectly calibrated and flawlessly constructed, exploded into absence. What emerged from the rubble was the regime’s story—a narrative of miraculous escape and divine favor that Hitler rushed to exploit, casting himself as a leader preserved by Providence to complete Germany’s destiny.

For the Gestapo, the blast was less a miracle than an intolerable breach. Within hours, Heinrich Himmler mobilized the full machinery of the security state. Roadblocks swept across southern Germany. Witnesses were interrogated until the small hours. By nightfall, a thin lead emerged: border guards had detained a man trying to cross into Switzerland with suspicious tools and sketches in his pocket. His name was Georg Elser.

Elser’s interrogation was brutal. He was beaten, tortured, and deprived of sleep. Yet he remained defiant, refusing to invent accomplices, refusing to give the Gestapo the foreign conspiracy narrative it desperately wanted. Eventually, under overwhelming pressure, he provided a simple, devastating truth: he had acted alone. He believed that Hitler had plunged Germany into war, destroyed workers’ rights, crushed dissent, and must be stopped before catastrophe broadened. “I wanted to prevent greater bloodshed,” he told his captors. To Himmler, this was intolerable—not because it was false, but because it was true.

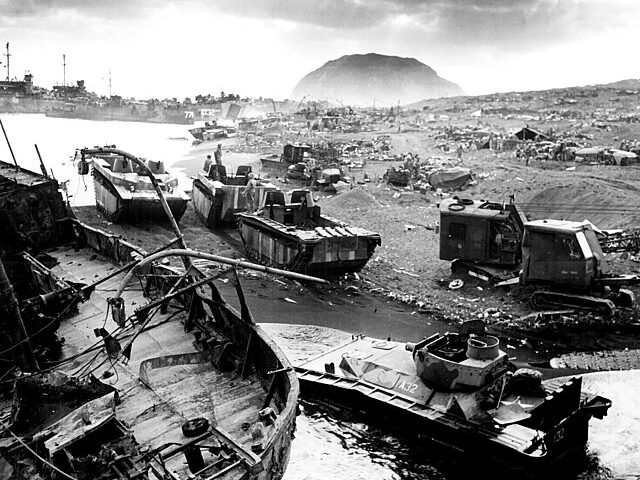

For six years, Elser disappeared into the Nazi prison system. He was transferred from Sachsenhausen to Dachau, held as a “special prisoner,” repeatedly interrogated for evidence of British involvement that never emerged. Even as the war turned against Germany, the regime kept him alive, hoping he might still prove useful in propaganda or negotiations. But by April 1945, with the Third Reich collapsing and Allied troops closing in, Himmler ordered the elimination of “dangerous” prisoners. On April 9, eight days before American forces liberated Dachau, Georg Elser was taken to the camp’s crematorium and shot.

What Elser left behind was not a political manifesto or a heroic resistance cell, but something more unsettling to totalitarianism: a solitary conscience that refused to bend. His act was not born of ideology or factional struggle but of a moral clarity that Nazism could neither comprehend nor tolerate. In Elser’s basement workshop, the Nazi state encountered a man who understood what millions would learn only through years of devastation—that Hitler’s Germany had set itself on a path that could only end in ruin, and that one individual, acting at the right moment, might alter the trajectory of history.

That moment passed on November 8, 1939. Thirteen minutes made the difference. The war that followed reshaped the world.