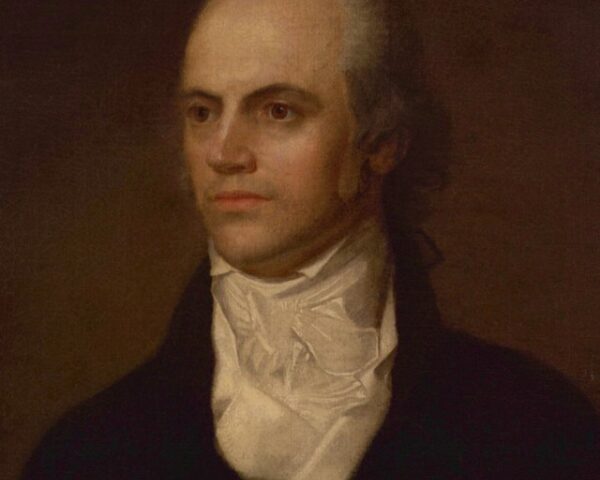

The events of November 9, 1307, sit at the center of one of medieval Europe’s most enduring political dramas: the suppression of the Knights Templar. On that day, Hugues de Pairaud—one of the order’s highest-ranking officers in France—was compelled under duress to issue a formal confession to the charges King Philip IV’s government had leveled against the Templar brotherhood. His forced admission, extracted in the opening weeks of what became a years-long campaign of interrogation, torture, and judicial manipulation, offered the French crown the documentary proof it needed to justify dismantling one of Christendom’s most powerful military-religious institutions.

Hugues de Pairaud was not a peripheral figure. As Visitor of France and a senior provincial official, he oversaw large swaths of the order’s administration and reported directly to the Grand Master, Jacques de Molay. To secure a confession from such a man in the first month of the trials carried immense symbolic weight. It suggested a breach within the order, a disintegration of unity, and—more importantly for Philip IV—a validation of the extraordinary charges being promoted by the royal inquest. Those accusations ranged from heresy and idol worship to financial corruption, illicit initiation rites, and blasphemy. Even by the tumultuous standards of fourteenth-century ecclesiastical politics, the allegations were sensational.

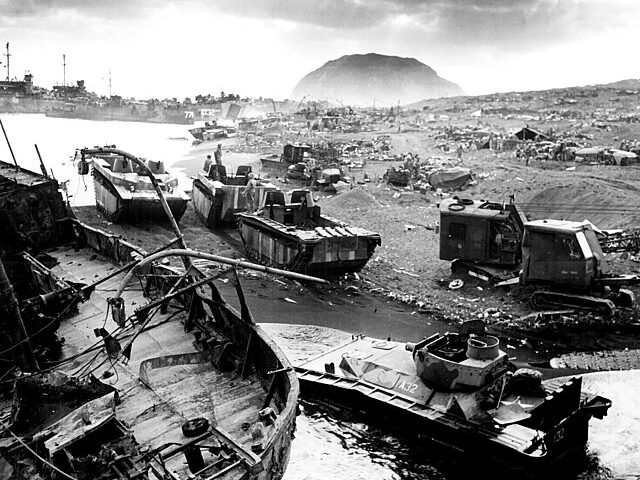

The context matters. On October 13, 1307, Philip had ordered the simultaneous arrest of Templars across France, seizing their property and detaining both rank-and-file brothers and senior officials. The speed of the operation reflected the king’s long-standing grievances. The crown owed the Templars substantial debts, the order’s independent networks of wealth and fortifications posed a challenge to royal authority, and Philip’s court—particularly his ruthless advisor Guillaume de Nogaret—viewed the Templar leadership as insufficiently pliant. The trials thus unfolded against a backdrop of political desperation, fiscal crisis, and the king’s ambition to break any institution he could not control.

Pairaud’s interrogation began almost immediately. Accounts from surviving trial records show that royal agents pressed him aggressively, employing the techniques that had already produced confessions from other brothers: sleep deprivation, shackling, threats, and, in many cases, torture. Under such conditions, the line between admission and self-preservation grew thin. Chroniclers later observed that the confessions secured in those early weeks shared suspicious uniformity, often mirroring the precise narrative the crown sought to establish.

On November 9, after repeated interrogations, Pairaud capitulated. He acknowledged—according to the minutes drawn up by the royal notaries—the improper initiation rites and heretical practices the prosecutors insisted were endemic within the order. The reliability of this confession, like many from the period, was compromised from the outset. Medieval inquisitorial practice prized admission over accuracy, particularly when torture was applied, and royal officers had every incentive to present the confession in its most damaging form. Yet the fact of the confession, rather than its truthfulness, was what mattered politically.

Once Pairaud’s statement was secured, Philip’s propagandists leveraged it to argue that even the order’s senior officials admitted grave wrongdoing. If a top officer could “confess,” then the order as a whole—so the reasoning went—must indeed be corrupt. This provided a powerful tool both for pressuring Pope Clement V and for persuading previously skeptical regional authorities that the Templars represented a genuine threat to Christian society. Clement, who had initially resisted Philip’s unilateral arrests, soon found himself boxed in. While he launched his own papal inquiry, the momentum of the French proceedings and the confessions emerging from them eroded any space he might have had to defend the order publicly.

Pairaud’s November 9 confession did not end his ordeal. He was subjected to further questioning, sometimes recanting, sometimes reaffirming his earlier statements depending on who held jurisdiction at the moment. His wavering echoed the experiences of many Templars who oscillated between defiance and compliance as political, ecclesiastical, and physical pressures shifted. By the time the Council of Vienne formally dissolved the order in 1312, the fate of men like Pairaud had long been sealed.