November 21, 1920, entered the lexicon of Irish history as “Bloody Sunday,” a day when violence in the Irish War of Independence erupted with unprecedented ferocity and irreversible consequences. In the space of a few hours, the conflict between the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and British authorities in Dublin burst into the open in a way that neither side could retreat from. What unfolded that morning and afternoon marked a decisive escalation in the struggle over Ireland’s political future and helped reshape how the British public understood the conflict across the Irish Sea.

The day began before dawn, when units of the IRA’s Intelligence Directorate, operating under Michael Collins, fanned out across Dublin with a list of carefully selected targets. Collins had spent months constructing an intelligence network that penetrated the British administration in Ireland, identifying more than a dozen operatives embedded in what was known as the Cairo Gang—the nickname for a group of British intelligence officers, informants, and detectives operating out of boarding houses and private lodgings around the city. According to Collins and his aides, these operatives posed an existential threat to the IRA, given their role in infiltrating Republican circles, building informant networks, and coordinating counter-insurgency operations.

Shortly after 9 a.m., IRA gunmen knocked on doors, forced entry into rooms, and carried out coordinated assassinations. Fourteen men were killed or fatally wounded, including several British Army officers and suspected intelligence operatives. Some victims were shot in front of their families; others were dragged from beds and executed. Though accounts differ over whether every target was actively involved in intelligence work, British authorities quickly acknowledged that their intelligence apparatus had suffered a severe blow.

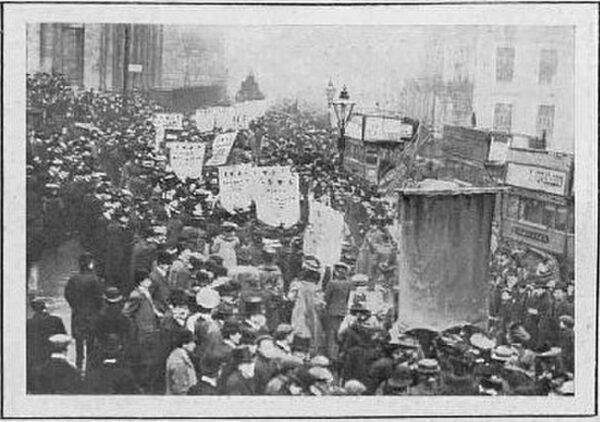

The killings sent shockwaves through the British administration at Dublin Castle. Senior officials were stunned by the precision of the operation, the breadth of IRA penetration into their ranks, and the sheer audacity of an orchestrated strike on British intelligence officers in the heart of a major city. London newspapers began reporting the deaths within hours, portraying the killings as murder on a scale unseen in the conflict thus far. For the British government, the attack challenged the credibility of its assurances that it possessed the intelligence and resources to suppress the independence movement.

But the morning’s violence was only the beginning.

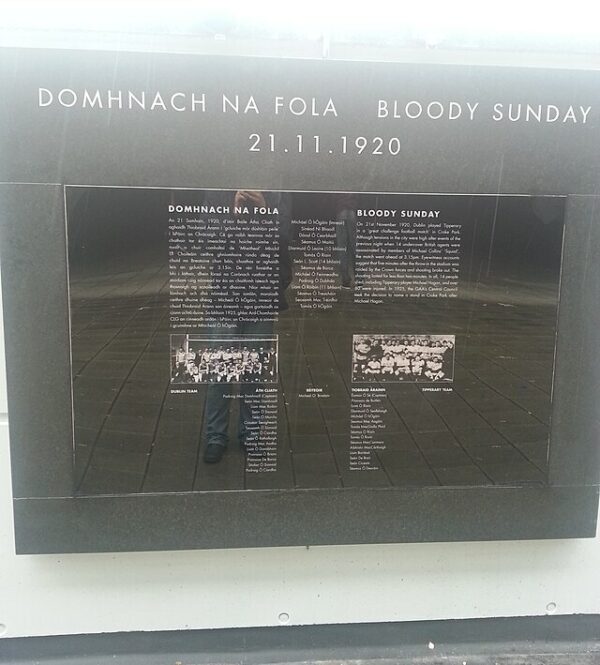

That afternoon, as thousands gathered at Croke Park for a Gaelic football match between Dublin and Tipperary, British forces staged a retaliatory raid. Shortly after 3:15 p.m., a mixed group of Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) officers, Auxiliaries, and British Army personnel entered the stadium grounds. What happened next remains one of the most contested moments of the war. British authorities claimed they were fired upon by IRA gunmen positioned among the spectators. Irish witnesses, including players and civilians, insisted no such shots were fired.

What is undisputed is the outcome: security forces opened fire on the crowd. Spectators screamed and scattered as bullets tore through the playing field and stands. Fourteen civilians were killed, including a young woman, Jane Boyle, who had been attending the match with her fiancé, and a ten-year-old boy, Jerome O’Leary. Dozens more were wounded. The massacre became one of the war’s darkest chapters, its brutality seared into the public imagination.

That evening, British forces killed three IRA detainees at Dublin Castle, claiming they were shot while attempting to escape—an explanation widely rejected by Irish nationalists.

By the day’s end, nearly thirty people were dead. Newspapers in Britain described the killings of the intelligence officers as savage criminality; Irish papers portrayed the Croke Park shootings as an atrocity against innocent civilians. International observers, particularly in the United States, reacted with horror.

Bloody Sunday became a turning point. For the IRA, the morning assassinations demonstrated its strategic reach. For Britain, the afternoon killings at Croke Park became a political liability. And for the Irish public, the day solidified the sense that the conflict had reached a threshold from which neither side could easily retreat.