In the winter of 1861, as the Union cracked under the pressure of secession and the first year of civil war drew to a close, the Confederate States of America undertook a ritual of nationhood it hoped would signal permanence. On December 4, 1861, the 109 presidential electors of the breakaway republic cast their ballots unanimously for Jefferson Davis as president and Alexander H. Stephens as vice president—an outcome foreordained by months of political maneuvering, yet still treated by Confederate leaders as a moment of constitutional dignity in the midst of national rupture.

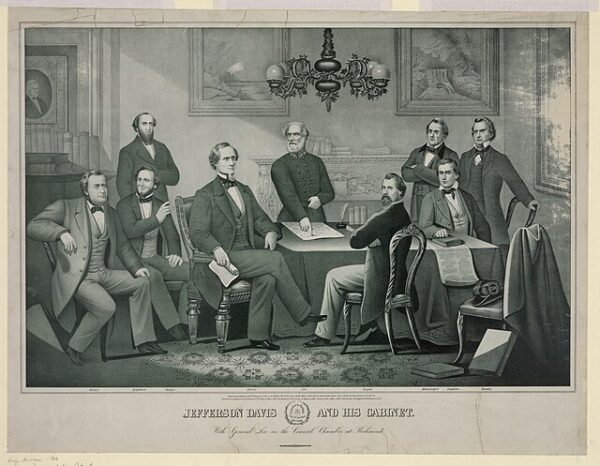

The vote marked the transition from the provisional government formed in February to the “permanent” Confederate administration authorized under its new constitution. Davis, who had been serving as provisional president since Montgomery, was thus formally elevated for a six-year term. Stephens, his uneasy partner—an intellectual, slight in stature yet formidable in rhetoric—retained the vice presidency. Both men had long been the obvious choices: Davis as the soldier-statesman whose Mississippi pedigree and congressional experience made him the most credible national figure the Confederacy could offer; Stephens as the Georgian moderate whose nomination had been calculated to reassure reluctant Upper South unionists even as he delivered, nine months earlier, the infamous “Cornerstone” speech declaring the Confederacy grounded on slavery’s supposed natural order.

Yet the unanimity of the electors obscured a deeper tension. The Confederate project, barely ten months old, already bore the marks of strain—military, economic, and ideological. Davis’s confirmation merely affirmed the concentration of executive authority in a wartime president who distrusted overt politics, valued discipline over persuasion, and prioritized military unity above all. His leadership style—stern, methodical, and intolerant of internal dissent—was cemented by the electoral ritual. If anything, the unanimous vote signaled not consensus but the absence of a viable alternative in a political system built on rebellion yet fearful of disunion within its own ranks.

The Confederate Constitution prescribed a mechanism resembling the U.S. Electoral College but designed to strengthen state sovereignty and limit majoritarian drift. Electors were chosen by popular vote within each state, though the Confederacy’s political culture—fragmented, planter-dominated, and increasingly militarized—ensured little genuine contestation. By December the Confederacy had admitted eleven states, though not all were equally represented: the elector count itself reflected substantial Unionist enclaves, contested territories, and the uneven reach of Confederate civil authority. Nonetheless, the machinery of election moved forward, a symbolic demonstration that a self-described constitutional republic could carry on even as its armies fought to break the one from which it had split.

Davis received word of the electors’ unanimous decision with characteristic sobriety. His public remarks framed the vote not as a personal triumph but as evidence that the Confederate cause rested on unity of purpose rather than the charisma of any individual leader. He pledged perseverance, sacrifice, and fidelity to the principles of states’ rights—though, as the war would increasingly reveal, the demands of modern conflict would push his administration toward centralized power at odds with the ideology that had justified secession. Stephens, meanwhile, offered dutiful acceptance but remained ambivalent about Davis’s martial instincts and the sweeping wartime measures he believed endangered civil liberty. The two men, united on paper, represented fundamentally different constitutional visions.

Outside the halls of government, the news drew little celebration. The Confederacy’s prospects in late 1861 were mixed. The early optimism of Fort Sumter and First Manassas had yielded to the grim realization that the Union would not collapse quickly. Blockades tightened, manufacturing lagged, and the limits of volunteer enthusiasm became evident. In that atmosphere, the electors’ vote functioned less as an expression of democratic vitality than as a gesture of resolve: a signal that the new nation would press forward, institutionalizing itself even as the war’s trajectory grew uncertain.