London in the 1760s was a city in the midst of profound commercial and cultural transformation. The Seven Years’ War had recently concluded, redirecting wealth and attention back toward domestic pursuits; aristocratic collections, gentlemanly libraries, and cabinets of curiosity were flourishing; and the city’s expanding middle classes were beginning to cultivate their own tastes for art, antiquities, and refinement. Into this energetic, competitive marketplace stepped James Christie, an ambitious newcomer who would reshape the world of auctions. On December 5, 1766, he held his first official sale—an event modest in scale but immense in consequence, marking the birth of what would become Christie’s, one of the most storied art-auction houses in the world.

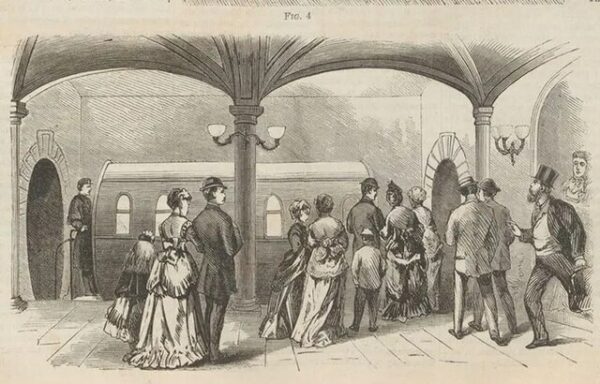

Little is known about every detail of that inaugural sale, yet contemporary accounts and later company histories suggest a scene characteristic of the era’s bustling London auction culture. Christie, then only in his late twenties, had acquired rooms on Pall Mall, strategically positioned near gentlemen’s clubs, royal residences, and the established art-dealing circles of St. James’s. Auctions in eighteenth-century London were often theatrical affairs, equal parts commerce and performance, in which the auctioneer’s charisma mattered almost as much as the objects on offer. Christie distinguished himself early with a combination of polished manners, quick wit, and an instinct for turning the auction podium into a stage. His very first sale demonstrated his aptitude for attracting attention, building relationships, and projecting authority in a crowded, competitive marketplace.

The goods he offered that December afternoon were typical of the period: household furnishings, decorative objects, secondhand goods, and small curiosities. This was not yet the realm of Old Masters and princely collections for which Christie’s would later become famous. But these early sales were foundational. They allowed Christie to cultivate a client base drawn from London’s rising commercial classes as well as from the aristocracy, who appreciated both the convenience and the prestige of a well-run auction room. The act of selling “by the hammer” was itself gaining sophistication in these years, and Christie helped standardize practices—carefully printed catalogues, consistent schedules, and a cultivated air of decorum—that gave auctions an aura of reliability and even social distinction.

Christie’s timing could hardly have been better. The mid-eighteenth century witnessed a dramatic expansion of collecting culture in Britain. The Grand Tour, which sent young aristocrats across Europe in search of artistic refinement, had generated a taste for classical sculpture, Renaissance painting, and continental luxury goods. New money from trade and industry was circulating in London, creating a class of aspirational collectors eager to acquire objects that signaled status and learning. Meanwhile, estates from older aristocratic families were periodically broken up, releasing significant works of art and literature into the market. Christie’s early sales tapped directly into these currents: he offered a mechanism for transferring cultural capital, and his growing reputation assured buyers and sellers alike that the process would be efficient, transparent, and dignified.

By the 1770s and 1780s, Christie had expanded beyond his modest beginnings. He received consignments from prominent collectors, handled portions of major estate dispersals, and secured a foothold in the world of fine art auctions. He often entertained and negotiated with clients in his Pall Mall rooms, cultivating relationships that would sustain the business long after his death. His partnership with influential dealers and his occasional direct correspondence with aristocratic patrons helped solidify Christie’s shift from an auctioneer of miscellaneous goods to a respected broker of cultural treasures.

The sale of December 5, 1766, thus stands as more than a historical footnote. It represents the earliest milestone in a trajectory that carried Christie’s from a small London auction room to global prominence. Today, the company he founded routinely sells masterpieces by Rembrandt, Picasso, and Monet, handling billions of dollars’ worth of art each year. Yet its origins remain rooted in Christie’s own entrepreneurial instincts and the evolving marketplace of eighteenth-century London—an era when the hammer first fell in a room on Pall Mall, setting in motion a legacy that would reshape the art world for centuries to come.