The Root and Branch Petition, presented to the Long Parliament on December 11, 1640, stands as one of the most provocative and destabilizing petitions of the English Reformation era. Signed by an estimated 15,000 Londoners—an extraordinary number for the period—it demanded nothing less than the abolition of episcopacy, the hierarchical system in which bishops governed the Church of England. Those who delivered it understood the stakes. They were not merely protesting a particular cleric or a transient policy; they were attacking the governing structure of the national church and implicitly challenging royal authority, since Charles I regarded episcopacy as an essential buttress of monarchy.

To understand the deeper meaning of the petition, one must recall the religious and political anxieties of early Stuart England. Since the accession of James I in 1603, Puritan discontent with the established church had simmered, occasionally surfacing in parliamentary debates or pamphlet literature. Bishops were seen not only as ecclesiastical authorities but as political agents intertwined with royal power, vested with patronage, censorship authority, and jurisdiction over local life. When William Laud ascended to the archbishopric under Charles I, he attempted to enforce ceremonial conformity, emphasizing liturgical beauty, sacramental theology, and strict discipline. Many Puritans viewed Laud’s program as evidence of creeping “popery,” a restoration of Catholic forms under Protestant guise. The episcopal system, in their minds, enabled this authoritarian program to unfold.

The Root and Branch Petition did more than call for reform; it called for unwinding the structure “root and branch,” eliminating not only individual bishops but the entire system from which their authority sprang. “Root and branch”—a phrase that had appeared in sermons and polemical writings since the Elizabethan period—captured an unmistakable sentiment: incremental reform was insufficient because the tree itself was corrupt. Those circulating the petition understood that religious government could not be extricated from political governance. Bishops sat in the House of Lords; they were royal administrators; they shaped law and discipline. To abolish episcopacy would therefore weaken royal power and strengthen Parliament and the godly urban constituency that had come increasingly to identify with the Puritan cause.

The petition’s scale was remarkable. Unlike many elite political interventions of the early seventeenth century, this was a broadly subscribed civic action centered in London parish life. The city’s political culture had changed dramatically as merchants, artisans, and religious activists read and exchanged printed literature, debated sermons, and organized civic campaigns. London was the engine of the Puritan movement, fueled by professional guilds, trading companies, and neighborhood congregations. That 15,000 Londoners signed this document testified to an organized urban energy—to a community convinced that ecclesiastical reform would advance civic liberty, honest preaching, and local autonomy. In many respects, this was a precursor to modern mass politics: coordinated, strategically framed, highly public, and deliberately inserted into parliamentary deliberation.

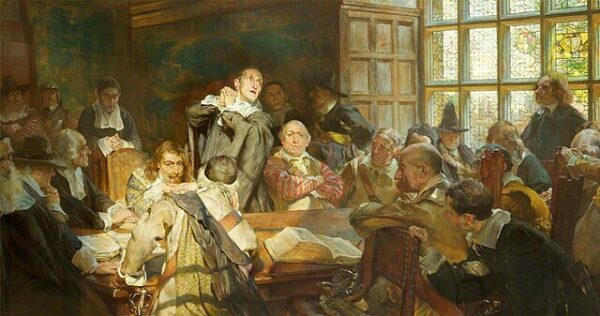

When the petition reached the Long Parliament, it immediately divided members. Some—including John Pym and the more radical Puritan contingent—treated episcopacy as inseparable from political oppression. They believed a reformed religious settlement would require dismantling the existing governing structure and replacing it with presbyterian or congregational frameworks that placed ministerial authority closer to local congregations. Others in Parliament, including constitutional conservatives and moderate Anglicans, resisted the demand. To them, the episcopal system preserved the integrity and unity of the national church and provided a stabilizing force in a society already rattled by royal mismanagement, economic uncertainty, and constitutional breakdown. Abolishing bishops seemed reckless, perhaps revolutionary.

The Root and Branch Petition did not achieve immediate legislative victory. Rather, it opened a sustained debate that would continue through the 1640s, culminating in the temporary abolition of episcopacy during the English Civil War and the rise of Presbyterian and Independent systems under the Commonwealth. Yet its real importance lay in its public character. It demonstrated that religious structure could not be quarantined from constitutional questions. The petitioners insisted that ecclesiastical authority shaped liberty, property, community, and governance. If one wished to free English society from royal absolutism, one must uproot the institutional trunk that supported it.

In retrospect, the petition’s ramifications extended far beyond administrative church questions. The intense parliamentary debate made visible a new political logic: organized public opinion—expressed through signatures, sermons, pamphlets, and civic mobilization—could redirect national policy. In a society where monarchy traditionally monopolized legitimacy, the Root and Branch Petition suggested that the community of the godly could act collectively as a constitutional actor. This was not yet democracy, but it marked a breach in the assumptions of Stuart authority and contributed to the intellectual architecture that later sustained parliamentary sovereignty.

Its legacy also mattered for religious liberty. By undermining episcopal inevitability, the petition opened ideological space for competing ecclesiastical frameworks to flourish. Presbyterianism, congregationalism, and later Baptist and Independent forms gained credibility because episcopal uniformity no longer appeared compulsory. The petition therefore stands at the beginning of a broader constitutional transformation in which English identity was gradually disentangled from compulsory religious conformity.