On December 23, 1688, James II of England fled England for France, bringing to a close one of the most decisive constitutional crises in English history. His flight—effectively an abdication—marked the culmination of the Glorious Revolution, a political upheaval that replaced a reigning monarch without a civil war and permanently redefined the relationship between the English crown and Parliament. In James’s place, Parliament would recognize his Protestant daughter Mary II of England and her husband, William of Orange, as joint sovereigns.

James II had ascended the throne in 1685 following the death of his brother, Charles II. Almost immediately, his reign unsettled England’s political and religious establishment. James was openly Catholic in a kingdom that had defined itself, both theologically and politically, in opposition to Rome since the Reformation. More alarming than his faith alone was his governing philosophy. James believed firmly in royal prerogative and sought to rule without parliamentary interference, suspending laws by decree, appointing Catholics to high offices in defiance of statute, and maintaining a standing army that many feared could be used to impose absolutist rule.

For several years, opposition remained fragmented. Many English elites hoped James’s reign would be short and that the crown would pass peacefully to his Protestant daughter Mary, already married to William of Orange, the leading Protestant ruler in Europe and a determined opponent of French Catholic power. That assumption collapsed in June 1688 with the birth of James’s son, James Francis Edward Stuart. The arrival of a Catholic male heir raised the prospect of a permanent Catholic dynasty, transforming political anxiety into outright alarm.

In response, a group of prominent English nobles and parliamentarians—later known as the “Immortal Seven”—secretly invited William of Orange to intervene. William landed in England in November 1688 with a substantial army, claiming he sought only to defend English liberties and secure a free Parliament. James’s support evaporated with astonishing speed. Key commanders defected, including John Churchill, the future Duke of Marlborough. Even James’s younger daughter, Anne, withdrew her loyalty. Faced with collapsing authority and unwilling to risk civil war, James attempted to flee.

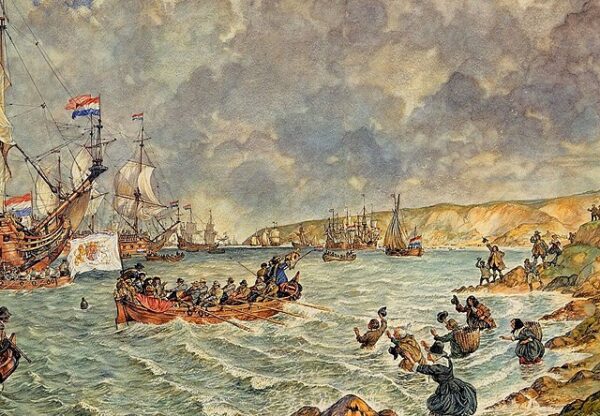

His first escape attempt failed when he was captured in Kent, but William deliberately allowed him another chance. A clear break, rather than a contested deposition, suited William’s political strategy. On December 23, James successfully escaped, crossing the Channel and making his way to Paris, where he was received by his cousin and ally, King Louis XIV of France. England, notably, did not pursue him. His flight was treated as abandonment of the throne rather than a forcible overthrow.

With James gone, Parliament faced a constitutional dilemma. No English monarch had ever been formally deposed by parliamentary action alone. The solution was revolutionary in its implications: Parliament declared that James had abdicated by fleeing and that the throne was therefore vacant. It then offered the crown jointly to William and Mary, who accepted under conditions that would fundamentally limit royal power.

Those conditions were codified in the Bill of Rights of 1689, which barred Catholics from the throne, prohibited the suspension of laws without parliamentary consent, outlawed standing armies in peacetime without approval, and affirmed the right of Parliament to meet freely. Sovereignty would no longer rest solely in the person of the monarch but in a constitutional partnership between crown and legislature. Unlike the bloody revolutions that would convulse Europe in later centuries, the Glorious Revolution achieved its aims with remarkably little violence—yet its consequences reshaped not only England, but the political development of the Atlantic world.