On December 30, 1813, British troops crossed the icy Niagara River and set fire to the American village of Buffalo, New York, reducing much of the settlement to ashes and marking one of the most destructive episodes along the northern frontier during the War of 1812. The attack was swift, punitive, and deeply symbolic—part of a brutal cycle of retaliatory violence that came to define the war’s final years.

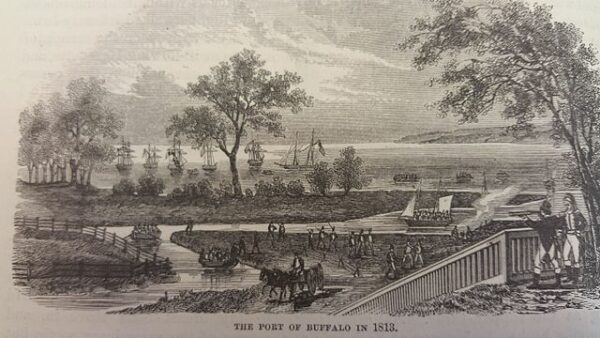

Buffalo in 1813 was not yet a city, but it was an important frontier village of roughly 1,500 residents. Located at the eastern end of Lake Erie, it served as a supply and staging point for American forces operating along the Niagara frontier. That strategic role made it a target when British commanders sought retribution for earlier American actions across the border.

The immediate context for the destruction of Buffalo lay in a series of American raids in Upper Canada earlier that month. U.S. forces had crossed the Niagara River and burned the Canadian village of Newark (modern-day Niagara-on-the-Lake), leaving hundreds of civilians homeless in the dead of winter. British authorities condemned the act as unnecessary and vowed retaliation. Major General Phineas Riall, commanding British forces in the region, prepared a counterstrike aimed at American settlements along the frontier.

Before dawn on December 30, British regulars, Canadian militia, and Native American allies crossed the frozen river near Black Rock, a small community just north of Buffalo. American defenses were weak and disorganized. Many militia units fled or failed to assemble, and regular army troops were too few to mount an effective resistance. The British quickly overwhelmed the limited opposition, capturing artillery positions and driving American forces inland.

With military resistance broken, the British advance turned destructive. Troops moved methodically through Black Rock and Buffalo, setting fire to homes, warehouses, taverns, and public buildings. By day’s end, nearly the entire village of Buffalo lay in ruins. Contemporary accounts estimate that more than 100 buildings were destroyed, leaving the population exposed to freezing temperatures with little shelter or supplies.

Though British officers issued orders intended to limit violence against civilians, the destruction was extensive. Some looting occurred, and fires spread rapidly in the winter winds. For Buffalo’s residents, the devastation was total. Families fled eastward into the countryside, many surviving the following weeks in makeshift shelters or with distant relatives.

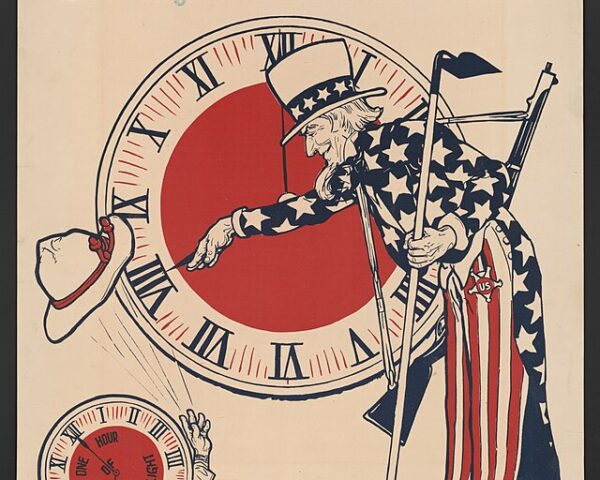

The burning of Buffalo shocked Americans and fueled outrage across the young republic. Newspapers described the attack in stark terms, portraying it as evidence of British cruelty and vindictiveness. The incident quickly became a rallying point for renewed calls to strengthen frontier defenses and continue the war effort, despite mounting war fatigue elsewhere in the country.

Strategically, the destruction of Buffalo underscored the vulnerability of the American northern frontier. The Niagara region, stretching between Lake Erie and Lake Ontario, had become one of the war’s most volatile theaters. Control shifted repeatedly, towns changed hands, and civilian populations bore the brunt of military decisions made far above them.

For the British, the attack achieved its immediate goal: retribution. It demonstrated that American raids on Canadian settlements would not go unanswered. Yet it also hardened American resolve and contributed to a growing sense that the war had descended into a cycle of destruction with diminishing strategic returns.

In the years after the war, Buffalo rebuilt rapidly. Its location and commercial potential soon transformed it from a burned-out village into a booming gateway to the Great Lakes, especially after the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825.