On December 31, 1759, a relatively obscure Irish brewer made one of the most consequential business decisions in history. Arthur Guinness, then 34 years old, signed a lease that would become legendary: a 9,000-year agreement on a dilapidated brewery site at St. James’s Gate in Dublin, at an annual rent of just £45. With that signature, Guinness began brewing on a scale—and with an ambition—that would eventually transform a local porter into one of the world’s most recognizable brands.

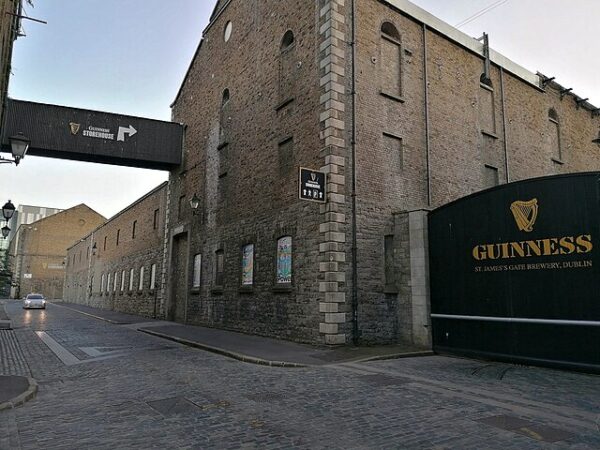

The site Arthur Guinness leased had been largely abandoned. St. James’s Gate had once housed a brewery, but by the mid-18th century it was run-down, equipped with only a small brewhouse and a few acres of land. The modest rent reflected the property’s condition rather than its potential. Yet Guinness saw what others did not: a location with access to clean water from the River Liffey, proximity to Dublin’s growing population, and room to expand.

Arthur Guinness was no novice. Born in 1724 in County Kildare, he had learned brewing under the patronage of Archbishop Arthur Price, who employed Guinness’s father and later provided Arthur with capital to start his own brewery. By the time he arrived in Dublin, Guinness had already established a reputation for diligence and technical skill. What distinguished him, however, was a long-term vision that bordered on audacity.

The 9,000-year lease—often cited as a symbol of supreme confidence—was less eccentric than it appears. Long leases were not uncommon in 18th-century Ireland, but the length of Guinness’s agreement was extraordinary even by contemporary standards. The lease granted Guinness stability, shielding him from rent increases and giving him the freedom to invest heavily in equipment, labor, and production capacity. It was a declaration that he intended not merely to brew beer, but to build an institution.

At first, Guinness brewed ales typical of the period. But by the 1770s, he shifted focus toward porter, a dark beer that had become popular among London laborers and was gaining traction in Ireland. This decision proved decisive. Guinness refined his porter recipe, emphasizing consistency and quality, and gradually abandoned other beer styles to specialize in the product that would define the brand.

The brewery at St. James’s Gate Brewery expanded steadily. By the time Arthur Guinness died in 1803, the operation had grown into Ireland’s largest brewery. His heirs—particularly his son Arthur Guinness II—continued to scale production, adopt new technologies, and push Guinness beyond Dublin and Ireland into Britain and, eventually, global markets.

The symbolic power of the lease grew over time. The idea of a 9,000-year commitment came to represent permanence, confidence, and patience—qualities increasingly rare in modern commerce. While the lease itself has since been renegotiated and effectively rendered obsolete by later property arrangements, its myth endures as a cornerstone of Guinness lore.

Beyond beer, Arthur Guinness’s legacy includes philanthropy and civic responsibility. The Guinness family became known for funding housing, healthcare, and social reforms in Ireland and Britain, linking commercial success with public good. This tradition reinforced the brand’s image not just as a brewer, but as a cultural institution embedded in Irish life.

What began on December 31, 1759, as a practical business transaction—ink on parchment, £45 a year—became a defining moment in industrial and cultural history. Arthur Guinness could not have known that his brewery would still be operating more than two and a half centuries later, nor that his name would be spoken in pubs on every continent. Yet the lease captured something essential about his approach: build carefully, think expansively, and commit for the long haul.