On January 1, 1892, a small island in New York Harbor officially became the primary gateway to the United States for millions seeking a new life. That morning, Ellis Island opened its doors as the nation’s first federally operated immigration station, marking a turning point in how America managed—and understood—mass immigration.

The first immigrant processed was Annie Moore, a 15-year-old girl from County Cork, Ireland, who arrived with her two younger brothers aboard the steamship Nevada. Her processing took only minutes. Officials asked a few basic questions, checked her health, and recorded her name. Moore received a ten-dollar gold piece from New York officials to commemorate the occasion. Within hours, hundreds more followed, unaware that their brief passage through Ellis Island would become one of the most iconic chapters in American history.

Ellis Island did not emerge by accident. During the mid-19th century, immigration had surged, particularly from Europe, as industrialization, famine, political unrest, and religious persecution pushed millions to leave their homelands. Previously, immigration had been handled by individual states, with New York operating a processing center at Castle Garden in lower Manhattan. But concerns over corruption, inconsistent enforcement, and the growing scale of arrivals led Congress to federalize immigration oversight in 1891. Ellis Island—isolated, expandable, and adjacent to the nation’s busiest port—was chosen as the solution.

The original Ellis Island facility, a large wooden structure, was designed to process up to 500,000 immigrants annually, a figure that would soon prove conservative. Immigration inspectors focused on two primary goals: excluding those deemed likely to become public charges and preventing the entry of individuals with contagious diseases. Contrary to popular myth, most immigrants were not subjected to long interrogations or arbitrary rejection. Roughly 98 percent were admitted. Medical inspections were rapid, often lasting only seconds, though chalk marks placed on coats could signal further examination.

For many immigrants, Ellis Island represented both hope and anxiety. After grueling transatlantic voyages in crowded steerage compartments, arrivals faced the fear that illness, disability, or misunderstanding might result in separation from family or forced return. Yet for those who passed inspection, the island marked the threshold of possibility—access to jobs, land, education, and political freedom unavailable in the Old World.

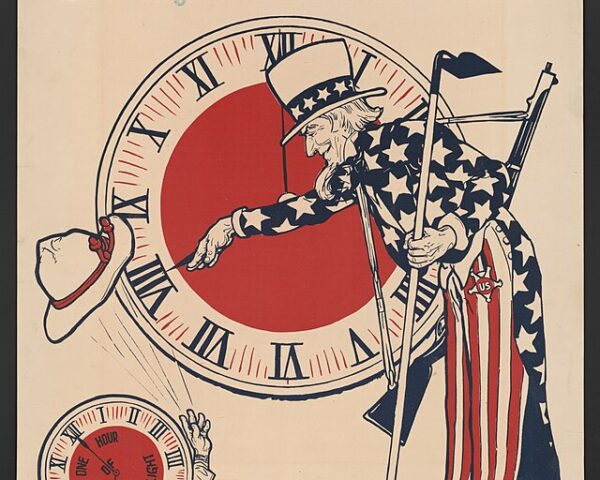

Ellis Island’s opening coincided with broader national debates over immigration, race, and American identity. The 1890s were an era of economic volatility, labor unrest, and rising nativism. While earlier immigrants from Northern and Western Europe had generally been welcomed, newer arrivals from Southern and Eastern Europe—Italians, Poles, Jews, Greeks, and others—faced suspicion and discrimination. Ellis Island thus stood at the intersection of aspiration and exclusion, symbolizing both America’s openness and its anxieties.

Over the next three decades, Ellis Island would process more than 12 million immigrants. At its peak in 1907, over one million people passed through in a single year. Many settled in urban centers like New York, Chicago, and Boston, while others moved westward, contributing labor to factories, railroads, mines, and farms. Their descendants would profoundly shape American culture, politics, and economic life.

By the 1920s, restrictive immigration laws sharply reduced arrivals, and Ellis Island’s role diminished. It closed as an immigration station in 1954 and later fell into disrepair before being restored as a museum. Today, it stands alongside the nearby Statue of Liberty as a powerful reminder of the nation’s immigrant past.