On January 2, 1777, at a narrow stream just south of Trenton, New Jersey, the American Revolution reached one of its most psychologically decisive moments. There, American forces under the command of George Washington successfully repulsed repeated British assaults led by Charles Cornwallis at what became known as the Battle of the Assunpink Creek. Though often overshadowed by the famous Christmas night crossing of the Delaware and the Battle of Princeton the following day, the stand at Assunpink Creek was the fulcrum on which the winter campaign turned.

The battle unfolded in the aftermath of Washington’s stunning victory at Trenton on December 26, 1776, where his army captured nearly 1,000 Hessian troops. That success, achieved after months of retreats and defeats, revived American morale but also drew an aggressive British response. Determined to crush Washington’s force, Cornwallis assembled roughly 8,000 seasoned troops and advanced toward Trenton from Princeton, confident that the battered Continental Army could be brought to decisive battle.

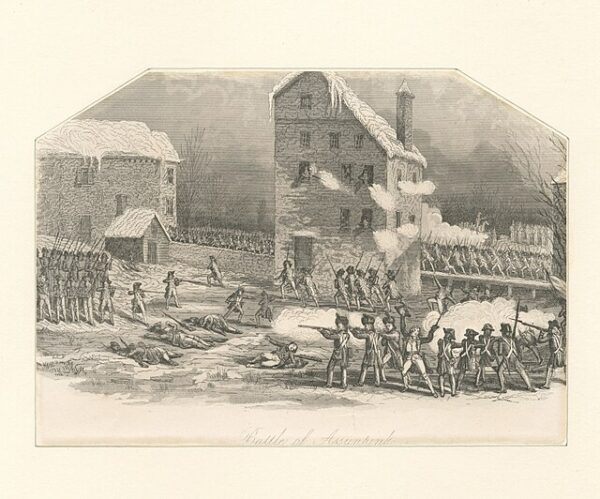

By the afternoon of January 2, Cornwallis’s column reached the outskirts of Trenton. Washington, commanding fewer than 6,000 men, chose not to retreat immediately. Instead, he drew up his defenses behind Assunpink Creek, a modest but strategically vital waterway crossed by a narrow stone bridge. The creek formed a natural defensive line, forcing the British to funnel their attacks into confined approaches while exposing them to American artillery and musket fire from higher ground.

Throughout the late afternoon and into the fading winter light, Cornwallis ordered repeated assaults against the bridge and nearby fords. British regulars advanced with discipline and determination, only to be met by concentrated cannon fire and volleys from American infantry. Each attempt to force a crossing was repelled. The creek ran red with blood, and British casualties mounted as daylight slipped away.

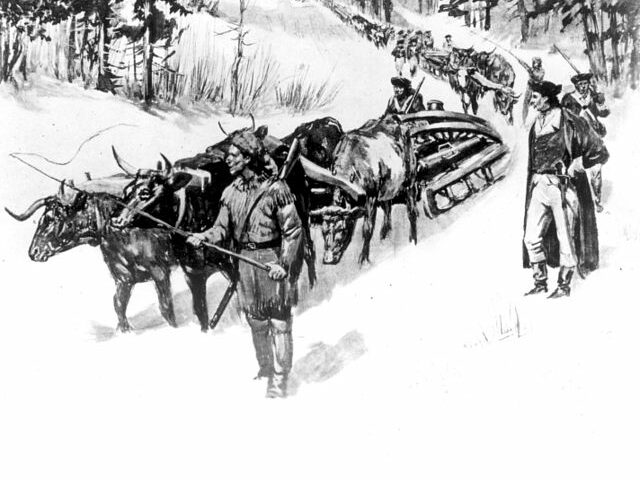

Frustrated but confident of ultimate victory, Cornwallis halted the attacks at nightfall. He believed Washington’s army was trapped against the Delaware River and famously remarked that the “old fox” would not escape by morning. British troops bivouacked within earshot of the American lines, while Washington’s men kept their campfires burning and cannons rumbling, maintaining the illusion that they were preparing to defend another assault at dawn.

What Cornwallis did not know was that Washington had no intention of remaining in place. During the night of January 2–3, the Continental Army executed one of the most audacious maneuvers of the war. Leaving a small force behind to tend the fires and maintain noise, Washington quietly withdrew the bulk of his army, marched around the British flank on frozen back roads, and headed toward Princeton. There, on January 3, the Americans would strike again, defeating British forces and securing yet another victory.

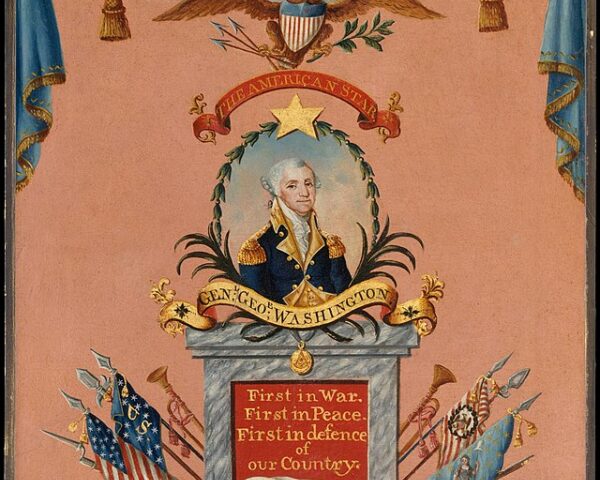

The stand at Assunpink Creek was thus not an end in itself but a masterful act of operational deception. By holding Cornwallis at bay for a single critical evening, Washington bought the time and space necessary to reposition his army and seize the initiative. The engagement demonstrated Washington’s growing confidence as a commander—his willingness to fight defensively, exploit terrain, and outthink a numerically superior enemy.

Strategically, the twin victories at Trenton and Princeton transformed the course of the war. They shattered the myth of British invincibility, persuaded thousands of American soldiers to reenlist, and encouraged foreign observers—particularly in France—to reconsider the viability of the American cause. The Battle of the Assunpink Creek, though brief and often overlooked, was the hinge of that transformation.

On a cold January evening in 1777, at a narrow New Jersey stream, Washington proved that the Continental Army could stand its ground against the British regulars—and, more importantly, that it could outmaneuver them.