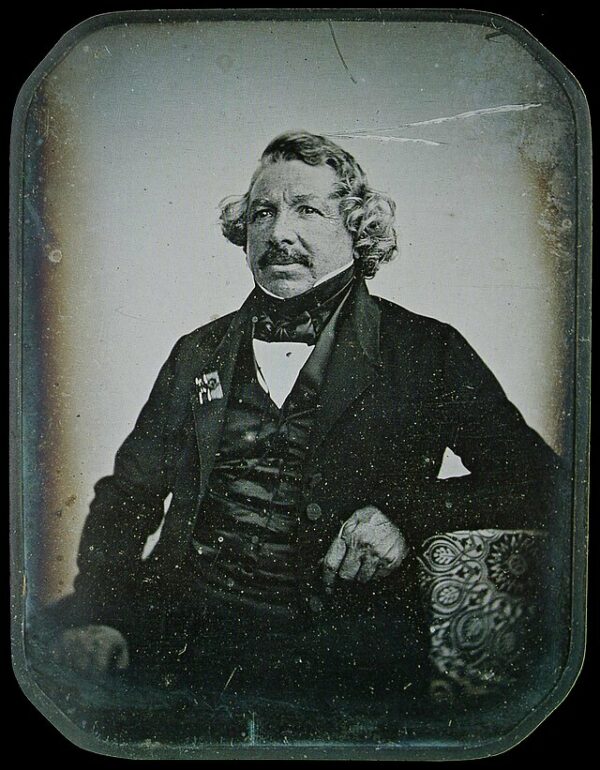

On a winter day in Paris on January 9, 1839, the modern world blinked into focus. Before a gathering of scholars and savants, the French Academy of Sciences announced that it would soon reveal a new method for fixing images from light itself—a process developed by the French artist and inventor Louis Daguerre. The name attached to it, daguerreotype, would quickly become synonymous with a technological rupture as consequential as the steam engine or the telegraph.

The announcement did not yet lay bare the full mechanics of the process. That would come later in the year. But the signal was unmistakable: photography had arrived, not as a parlor trick or curiosity, but as a reproducible, scientific technique capable of permanently capturing reality. What had previously required the interpretive hand of painters and engravers could now be accomplished by chemistry, optics, and time.

Daguerre’s breakthrough was the culmination of decades of experimentation aimed at solving a single, stubborn problem—how to make light leave a permanent trace. Earlier efforts, most notably by Nicéphore Niépce, had succeeded in capturing faint, unstable images that required hours of exposure and quickly deteriorated. Daguerre, who had partnered with Niépce in the 1820s, refined the approach after his collaborator’s death, discovering that iodine-sensitized silver plates exposed in a camera obscura could be developed using mercury vapor and fixed with salt solutions. The result was astonishing clarity—images of streets, buildings, and faces rendered with a precision no artist could rival.

The Academy’s decision to announce the process was itself significant. Rather than allowing Daguerre to guard his invention as a private monopoly, the French state moved swiftly to acquire the rights and make the method freely available to the world, describing it as a “gift to humanity.” In an era still defined by guilds and guarded secrets, this was a radical act of scientific republicanism—knowledge not hoarded, but released.

When the technical details were published later that year, the effect was electric. Studios sprang up almost overnight in Paris, London, New York, and Boston. Ordinary people—merchants, clerks, soldiers—could now sit for portraits that captured not an idealized likeness, but their actual faces, creases and all. History, once filtered through memory and myth, acquired an optical record.

The implications went far beyond art. Daguerreotypes reshaped journalism, science, and state power. Cities could be documented, monuments catalogued, distant colonies visually surveyed. For the first time, evidence could be shown rather than merely described. The authority of the image—so central to modern politics and media—began here, in silvered copper plates polished to a mirror finish.

Yet the process had its limits. Each daguerreotype was a singular object, impossible to reproduce. Exposure times were long, often requiring sitters to brace themselves with metal clamps. The images, though extraordinarily sharp, were fragile and could tarnish if mishandled. These constraints ensured that the daguerreotype’s dominance would be brief, soon overtaken by negative-based processes that allowed for mass reproduction.