On January 18, 1967, Albert DeSalvo was sentenced to life imprisonment in Massachusetts, closing one chapter of the most terrifying murder spree Boston had ever known—and opening a far more unsettling debate about guilt, justice, and the limits of certainty in criminal law.

By the mid-1960s, the name “Boston Strangler” had become shorthand for a particular kind of modern dread. Between 1962 and 1964, thirteen women—most of them elderly or living alone—were sexually assaulted and murdered in their apartments across the city. The crimes followed a grim pattern: forced entry without signs of struggle, ligature strangulation, and a chilling intimacy that suggested the killer had gained his victims’ trust. Boston, still marked by postwar optimism and urban stability, found itself gripped by fear. Women locked their doors in daylight. Neighbors watched one another with suspicion. Police faced mounting pressure to find the man responsible.

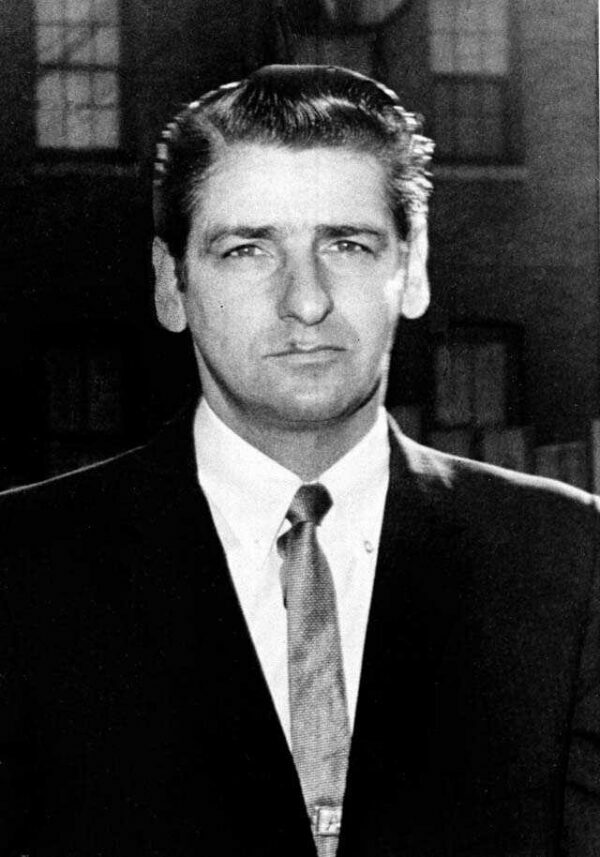

Albert DeSalvo entered the public eye not as a murderer but as a con man. Arrested in 1964 for a series of sexual assaults known as the “Green Man” attacks, DeSalvo had impersonated a handyman to gain entry into women’s homes. While in custody, he began to confess—to fellow inmates, to psychiatrists, and eventually to authorities—that he was also the Boston Strangler. His confessions were detailed, disturbing, and at times eerily consistent with facts known only to investigators. For a city desperate for resolution, the idea that the Strangler had finally been unmasked offered a kind of exhausted relief.

But the legal system confronted a problem it could not neatly resolve. DeSalvo was never formally tried for the Strangler murders themselves. The evidence tying him to the killings was largely circumstantial, and prosecutors worried that inconsistencies in his confessions—combined with questions about his mental health—could jeopardize a murder conviction. Instead, the state pursued charges for unrelated crimes: armed robbery, sexual assault, and other violent offenses that carried the possibility of a life sentence.

On January 18, 1967, DeSalvo was convicted of numerous counts and sentenced to life imprisonment. In practical terms, it ensured he would never walk free. In symbolic terms, it left Boston suspended between closure and doubt. The man widely believed to be the city’s most notorious killer would die behind bars, but without a courtroom verdict formally declaring him the Boston Strangler.

The sentence did little to quiet the controversies that followed. Some investigators believed DeSalvo’s confessions were credible, pointing to details he appeared to know before they were public. Others argued that he was a compulsive liar who had absorbed information from newspapers and police leaks. Skeptics noted variations in the murders themselves—differences in victim profiles, crime scenes, and methods—that raised the possibility of multiple killers. For families of the victims, the uncertainty was agonizing: justice felt both delivered and incomplete.

DeSalvo was sent to Walpole State Prison, where he lived under constant threat. Other inmates viewed him as a monster even by prison standards, and his notoriety made him a target. In 1973, he was stabbed to death in the prison infirmary under circumstances that were never fully clarified. His death ensured that many questions surrounding the Boston Strangler would never be answered directly.

Decades later, advances in forensic science reopened the case in limited ways. DNA evidence linked DeSalvo to the murder of Mary Sullivan, the youngest of the alleged Strangler victims, lending new weight to claims of his guilt—while still failing to conclusively tie him to all thirteen killings. The result has been a historical reassessment rather than a definitive verdict.

The January 1967 sentence remains a stark reminder of how justice sometimes operates in the shadow of uncertainty. DeSalvo was punished for what the state could prove, not necessarily for what the public believed. For Boston, the era ended not with a clear moral resolution, but with a lingering unease—an acknowledgment that even when a city believes it has found its monster, the truth can remain fractured, incomplete, and disturbingly out of reach.