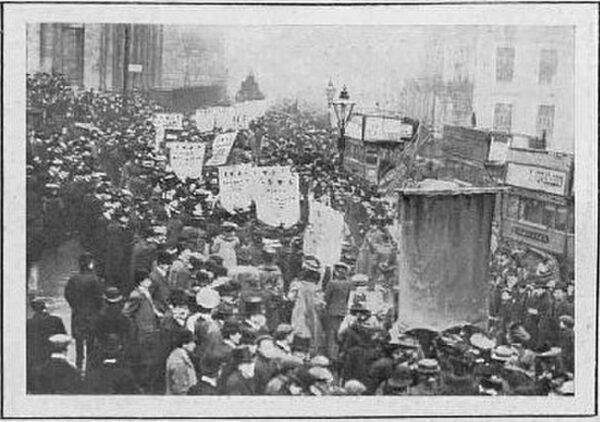

On January 20, 1265, in the mid-thirteenth century, a quiet but enduring revolution in English governance took place inside the great halls of what is now known as the Palace of Westminster. For the first time, an English Parliament convened that included not only the great lords of the realm and senior clergy, but also representatives of the major towns—burghers chosen to speak for communities whose economic weight had begun to rival the political authority of the nobility. The meeting marked a decisive step toward representative government and set England on a path that would ultimately reshape political life across the Atlantic world.

Until this moment, English kings governed through a narrow circle of magnates. Royal councils were dominated by earls, barons, and bishops whose power flowed from landholding, lineage, and proximity to the Crown. Towns, despite their growing importance as centers of trade, taxation, and population, were largely objects of governance rather than participants in it. Their wealth could be extracted; their voices could be ignored. What changed on that January day was not merely the composition of an assembly, but the underlying assumption about who had a right—or at least a necessity—to be heard.

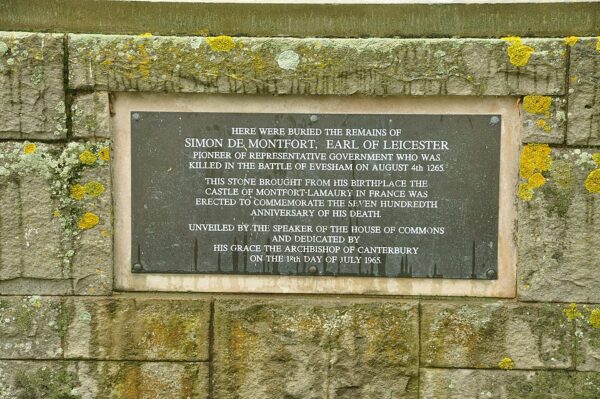

The immediate political context was instability. England was riven by conflict between King Henry III and a coalition of barons dissatisfied with royal finances, foreign favoritism, and perceived abuses of authority. At the center of this struggle stood Simon de Montfort, a nobleman who combined military force with an unusually expansive vision of political legitimacy. De Montfort understood that authority rooted solely in aristocratic consent was brittle. To govern—especially to tax—he needed broader buy-in.

The Parliament that gathered at Westminster reflected that calculation. Alongside lords spiritual and temporal sat elected representatives from counties and from key boroughs. These men were not peasants and they were not democrats in any modern sense. They were merchants, landholders, and civic leaders—members of a rising urban class whose prosperity underwrote the English economy. Yet their presence institutionalized a radical idea: political consultation should extend beyond the hereditary elite.

The location mattered. The Palace of Westminster was already the symbolic heart of royal authority, housing courts, councils, and ceremonial spaces. By bringing town representatives into that setting, the Crown—and its challengers—signaled that governance was no longer a private conversation among nobles. It was becoming, however incrementally, a national affair. Over time, this space would be known collectively as the Houses of Parliament, but its origins lay in this fragile experiment in inclusion.

The immediate consequences were uncertain. De Montfort’s political ascendancy was brief, and he would soon die on the battlefield. Henry III ultimately reasserted royal control. Yet the precedent could not be undone. Once towns had been summoned to Parliament, it became increasingly difficult to govern without them. Kings discovered that representative assemblies were useful—not because they limited power, but because they legitimized it. Consent, even constrained consent, proved more efficient than coercion alone.

Over the following centuries, the presence of town and county representatives hardened into custom, then expectation, and finally constitutional principle. The Commons emerged as a distinct body, initially subordinate but gradually assertive. Control over taxation became leverage. Grievance became negotiation. What began as a tactical move in a baronial power struggle evolved into a structural feature of English government.

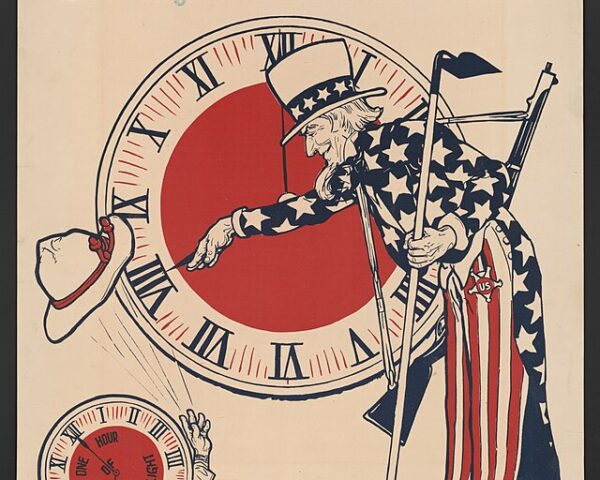

The January 20 assembly at Westminster thus occupies a peculiar place in history. It was neither democratic revolution nor mere formality. It was an improvisation—born of crisis, shaped by necessity, and preserved by utility. Yet its implications were vast. The idea that ordinary communities, organized through towns and counties, deserved representation would echo through later struggles: the English Civil War, the Glorious Revolution, and eventually the parliamentary traditions carried to North America.