On January 24, 1848, a carpenter named James W. Marshall bent down along the American River and unknowingly altered the trajectory of a continent. What he found glittering in the cold water near Sutter’s Mill was not merely a fleck of metal, but the spark that would ignite the California Gold Rush—a mass migration that reshaped the American economy, accelerated westward expansion, and hastened California’s violent, uneven transformation into a state.

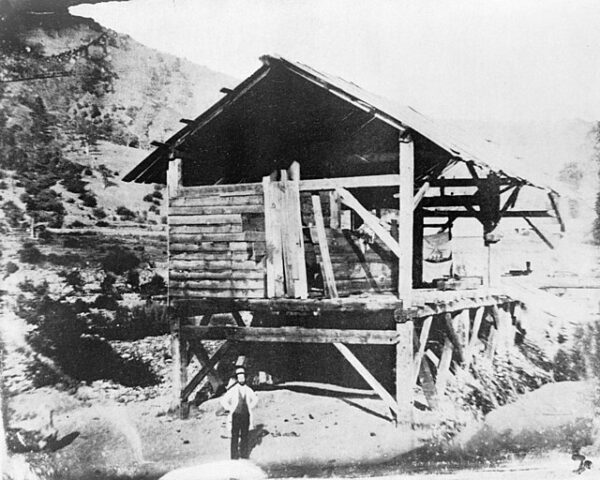

Marshall had been working on a sawmill for John Sutter, a Swiss immigrant and entrepreneur who envisioned an agricultural empire in Alta California, then newly transferred from Mexican to American control under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. The mill sat northeast of present-day Sacramento, in a quiet stretch of wilderness that promised timber, not treasure. Yet as Marshall inspected the tailrace after diverting the river overnight, he noticed several bright flakes caught in the gravel. He tested them crudely—hammering, biting, examining their color—and soon became convinced: it was gold.

The discovery was, at first, something to be concealed. Sutter feared—correctly—that news of gold would obliterate his labor force, destroy his farmland, and invite chaos. Marshall, too, hesitated. But gold has a way of escaping secrecy. Within weeks, rumors circulated among workers, then settlers. By March, San Francisco newspapers were reporting discoveries in the foothills. When President James K. Polk confirmed the reports in a December 1848 address to Congress, the trickle became a flood.

What followed was one of the most dramatic population movements in American history. In 1848, California’s non-Native population numbered perhaps 14,000. By the end of 1849, more than 100,000 fortune seekers—“Forty-Niners”—had arrived by wagon, ship, and foot, drawn from the eastern United States, Latin America, Europe, and China. San Francisco exploded from a sleepy port into a boomtown of tents, saloons, and speculation. Law lagged behind opportunity; improvisation became the rule.

The Gold Rush redefined the American West not as a distant frontier, but as an immediate economic engine. Gold financed railroads, banks, and industrial expansion back east. It helped stabilize U.S. currency at a moment of global uncertainty. California, catapulted by population growth and economic significance, bypassed the usual territorial phase and entered the Union as a state in 1850—a political acceleration with lasting consequences for the balance between free and slave states.

Yet the romantic imagery of lone prospectors obscures harsher realities. The Gold Rush devastated Native Californian communities, who faced displacement, disease, and organized violence as mining camps spread across ancestral lands. Environmental damage was immense: rivers choked with sediment, hillsides blasted apart by hydraulic mining, ecosystems permanently altered. The wealth extracted from California’s soil was unevenly distributed, enriching merchants and industrial operators more reliably than individual miners.

For Marshall himself, the irony was cruel. Despite being the man who discovered the gold, he never profited meaningfully from it. He died in relative poverty in 1885, his role celebrated in memory but unrewarded in life. John Sutter fared little better, watching his holdings disintegrate under the weight of squatters and lawsuits.

Still, January 24, 1848, endures as a pivotal moment in our history. The glitter Marshall spotted in the American River did more than launch a rush for riches; it accelerated the American experiment westward, with all the promise and peril that entailed. In the shimmer of that discovery lay the modern California—and, in many ways, the modern United States.