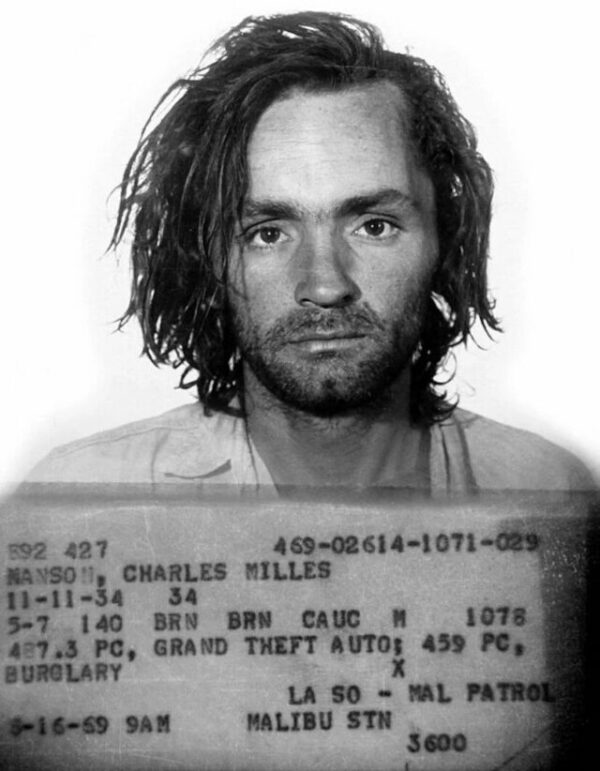

On January 25, 1971, one of the most infamous crime sprees in American history reached its legal conclusion. Charles Manson and four members of his so-called “Family” were found guilty for their roles in the brutal Tate–LaBianca murders, a verdict that brought a grim chapter of late-1960s America into sharp judicial focus.

The convictions stemmed from a series of killings carried out over two nights in August 1969 that shocked the nation with their randomness and savagery. At a rented home in Los Angeles, actress Sharon Tate—eight months pregnant—and four others were murdered. The following night, a Los Feliz couple, Leno and Rosemary LaBianca, were killed in their home. Though Manson did not physically carry out the attacks, prosecutors successfully argued that he orchestrated the violence through manipulation, indoctrination, and command.

The trial itself became a spectacle unlike any seen before in an American courtroom. Manson and his followers, many of them young women, cultivated an image that blended cultish devotion with open defiance of social norms. Court sessions were marked by outbursts, cryptic statements, and displays of loyalty that baffled observers and unsettled jurors. The defendants carved Xs into their foreheads, sang, and attempted to turn the proceedings into a stage for their apocalyptic worldview.

Central to the prosecution’s case was the argument that Manson exercised near-total psychological control over his followers. Though he did not personally wield a weapon during the murders, prosecutors contended that his directives were absolute—and deadly. The jury agreed, finding Manson guilty of first-degree murder and conspiracy, alongside four of his followers who had directly participated in the killings.

The verdict was widely seen as a repudiation not only of the crimes themselves but of the violent ideology Manson espoused. His belief in an impending race war—what he called “Helter Skelter”—was presented as the motive behind the killings, an attempt to ignite chaos and hasten societal collapse. In court, that ideology was stripped of its mystique and exposed as delusion weaponized through fear and obedience.

Public reaction to the guilty verdicts was swift and intense. For many Americans, the case symbolized the darker edge of the counterculture era—a moment when ideals of freedom and rebellion curdled into something far more sinister. Los Angeles County District Attorney Vincent Bugliosi, who led the prosecution, was credited with constructing a novel legal theory that held a charismatic leader accountable for crimes carried out by others at his behest.

Manson and his co-defendants were initially sentenced to death, though those sentences were later commuted to life imprisonment after California temporarily abolished the death penalty. Manson would remain incarcerated for the rest of his life, becoming a macabre cultural fixation even as decades passed.

The 1971 convictions closed the courtroom phase of one of America’s most infamous criminal cases, but their resonance endured. The Tate–LaBianca murders and the trial that followed reshaped how the justice system, the media, and the public understood cult dynamics, criminal conspiracy, and the power of coercive belief. More than half a century later, the verdict still stands as a stark reminder of how manipulation and violence can intertwine—and how the law, at least in this case, caught up with both.