On February 6, 1820, a small group of 86 African American emigrants departed New York aboard the ship Elizabeth, embarking on a journey that would bind the future of the United States to the West African coast in complicated and enduring ways. Sponsored by the American Colonization Society (ACS), the expedition marked the first organized attempt to establish a permanent settlement of free Black Americans in what would later become the nation of Liberia.

The American Colonization Society, founded in 1816, was a deeply paradoxical organization. Its membership included evangelical reformers who believed slavery was morally corrosive, political leaders who feared the presence of a growing free Black population, and enslavers who saw colonization as a way to strengthen slavery by removing free African Americans from the United States. Figures such as Henry Clay, Bushrod Washington, and Francis Scott Key supported the society, even as Black abolitionists overwhelmingly condemned it. For African Americans themselves, colonization was rarely a first choice; most considered the United States their home and viewed removal as an attempt to exile them from a country they had helped build.

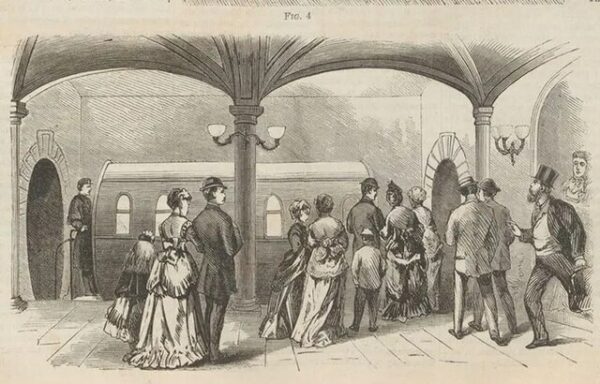

Yet by 1820, colonization had moved from theory to practice. The group that departed New York consisted largely of free Black Americans—some formerly enslaved—who volunteered or were pressured into joining the expedition. Many were motivated by a mix of hope and desperation: hope for self-government and dignity denied in the United States, and desperation born of pervasive racism, legal discrimination, and economic exclusion. They traveled under the authority of the ACS and with the support of the U.S. Navy, underscoring the quasi-official nature of the project.

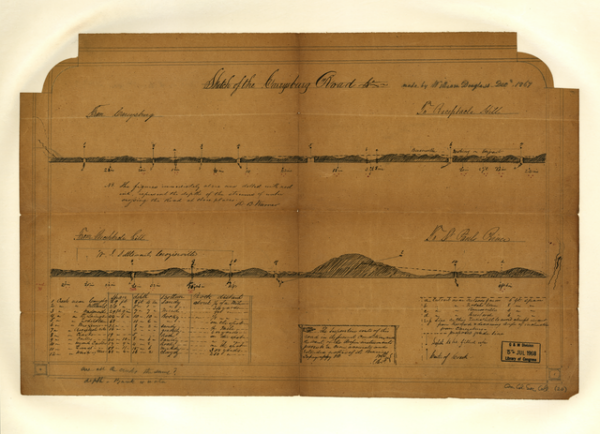

The voyage itself was arduous, and the challenges awaiting the settlers were even more severe. Upon arrival on the West African coast, the emigrants encountered unfamiliar terrain, tropical disease, and strained relations with local African communities. Malaria and yellow fever proved devastating; within months, a significant portion of the original settlers had died. Early attempts to establish a foothold on Sherbro Island failed catastrophically, forcing survivors to relocate to a healthier site along the Pepper Coast.

Despite these hardships, the settlement persisted. Over the following decades, thousands more African Americans would emigrate under ACS sponsorship. The colony gradually took shape, developing institutions modeled on those of the United States—churches, schools, a legislature, and a constitution. In 1847, Liberia declared independence, with its capital named Monrovia in honor of President James Monroe, a prominent supporter of colonization.

The legacy of the February 6, 1820 departure is inseparable from the contradictions of Liberia’s later history. The settlers and their descendants—often referred to as Americo-Liberians—came to dominate political and economic life in the new republic. They reproduced many American social hierarchies, governing over indigenous populations who were excluded from citizenship and political power for generations. In this sense, colonization exported not only American institutions but also American inequalities.

At the same time, Liberia became a powerful symbol in the Black Atlantic world. It represented one of the earliest modern experiments in Black self-rule, predating the abolition of slavery in the United States by more than four decades. For some African Americans, Liberia stood as evidence that people of African descent could govern themselves and participate fully in global diplomacy and trade.