On February 12, 1909—coinciding with the centennial of Abraham Lincoln’s birth—a small but determined coalition of Black and white reformers gathered in New York City to launch what would become one of the most consequential civil rights organizations in American history: the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

The founding of the NAACP did not come out of thin air. The first decade of the twentieth century was marked by racial violence, political retrenchment, and the systematic dismantling of Reconstruction-era gains across the South. Jim Crow laws had hardened into a rigid caste system: Black Americans were being disenfranchised through poll taxes, literacy tests, and grandfather clauses. Lynchings—often carried out publicly and with impunity—remained a grim reality.

The immediate catalyst for the organization’s formation was the 1908 race riot in Springfield, Illinois—the hometown of Lincoln himself. A white mob rampaged through Black neighborhoods, killing residents, destroying homes and businesses, and exposing the fragility of Black life even in Northern states. The riot shocked many white progressives who had believed such violence was largely confined to the South. It underscored a broader truth: racial injustice was national, not regional.

In response, a group of activists issued “The Call,” a public statement inviting concerned citizens to meet and confront what it described as the “renewed attempt to enslave” Black Americans through law and terror. Among the signatories were prominent figures such as journalist and anti-lynching crusader Ida B. Wells, sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois, and white reformers, including Mary White Ovington and Oswald Garrison Villard.

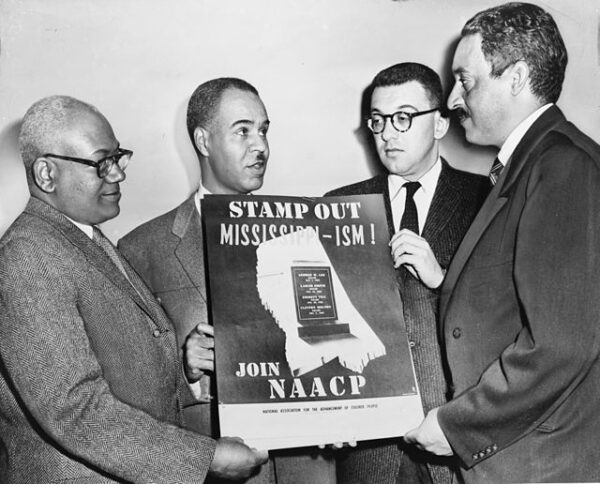

The February 12 meeting led to the formal creation of the NAACP, though the organization would adopt its full name the following year. From the outset, its mission was clear: secure for all citizens the rights promised under the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution. Unlike some contemporaneous movements that emphasized industrial education or economic self-help, the NAACP prioritized legal equality and political rights.

Central to its strategy was litigation. The organization quickly recognized that federal courts—however imperfect—offered one of the few viable avenues for challenging discriminatory laws. Under Du Bois’s intellectual leadership and through its publication, The Crisis, the NAACP also sought to shape public opinion, document racial violence, and cultivate a new generation of Black leadership.

The organization’s early legal victories were incremental but significant. It successfully challenged grandfather clauses designed to disenfranchise Black voters and fought segregation in housing and education. Over time, the NAACP would build a formidable legal apparatus, laying the groundwork for landmark Supreme Court decisions decades later, including Brown v. Board of Education in 1954.

Yet in 1909, such triumphs were far from assured. The founders often operated in a climate of hostility. White supremacist ideology enjoyed broad acceptance, and federal enforcement of civil rights protections was weak at best. Even within the Black community, there were debates about tactics and tone—most notably between Du Bois and Booker T. Washington—over whether confrontation or accommodation offered the wiser path forward.

The NAACP chose confrontation through law and advocacy. Its biracial leadership structure reflected an early commitment to interracial cooperation, even as it centered the voices and experiences of Black Americans. That structural choice—controversial to some at the time—helped the organization build national networks of funding and influence.

More than a century later, the NAACP remains active, a testament to the durability of the institution created in that Lincoln centennial year. What began as a response to mob violence in Illinois evolved into a cornerstone of the modern civil rights movement.