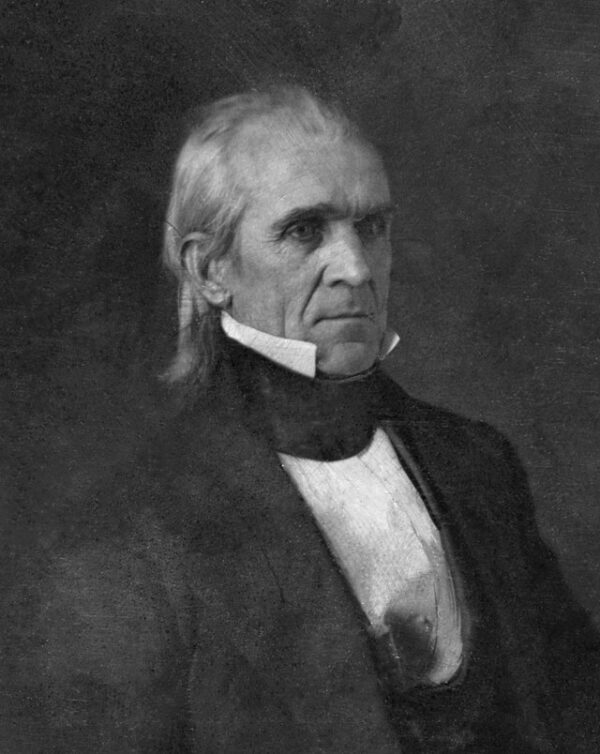

On February 14, 1849, in a New York City studio filled with harsh light and chemical fumes, a weary and soon-to-be former president sat motionless before a new and untested machine. In that moment, James K. Polk became the first sitting president of the United States to have his photograph taken—a quiet but profound turning point in the relationship between technology, politics, and the American public.

Polk was nearing the end of his single term in office. Just weeks remained before he would leave Washington and return to Tennessee, having pledged not to seek reelection. His presidency had been defined by relentless expansion and equally relentless work. Under his leadership, the United States annexed Texas, settled the Oregon boundary dispute with Great Britain, and prosecuted the Mexican-American War, which concluded with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and added vast western territories to the nation’s map. By the winter of 1849, Polk was physically exhausted, his health deteriorating after four punishing years.

The photograph taken that February day was a daguerreotype, the earliest commercially successful form of photography. Introduced to the United States only a decade earlier, the process required subjects to remain perfectly still for extended exposures. The result was a single, highly detailed image on a polished silvered plate. There were no negatives. Each portrait was unique.

Unlike painted presidential portraits, which softened features and flattered reputations, the daguerreotype was unsparing. Polk appears thin, tight-lipped, and severe. His high forehead and deep-set eyes project intensity rather than warmth. The image lacks the heroic flourish typical of nineteenth-century political art. Instead, it offers something unprecedented—the literal face of presidential power.

The timing was significant. Photography was still novel in 1849, but it was rapidly transforming American culture. Newspapers had already expanded dramatically in reach and influence. Railroads were shrinking distances. The telegraph, introduced commercially just a few years earlier, was accelerating communication. Now photography promised to fix reality itself in metal and light.

Polk’s decision to sit for a photograph—whether motivated by curiosity, legacy, or simple circumstance—signaled that even the presidency would not remain insulated from technological change. In the early republic, citizens often knew their leaders only through engravings, oil paintings, or written descriptions. These representations were interpretive, filtered through artistic convention. The camera removed a layer of mediation.

This shift carried political implications. Photography democratized access to power’s image. A president was no longer merely a distant symbol rendered in idealized form; he could be seen as he truly was: aging, tired, human. Over time, that shift would fundamentally alter political life. Abraham Lincoln’s carefully composed photographic portraits would help define his public image during the Civil War. Later presidents would learn to use photography strategically, understanding that visual presentation could shape perception as much as policy.

Within months of sitting for the portrait, Polk would leave office. He died just over three months later, in June 1849, making his photograph one of the last images captured of him during his lifetime. From that point forward, no president would remain unseen.