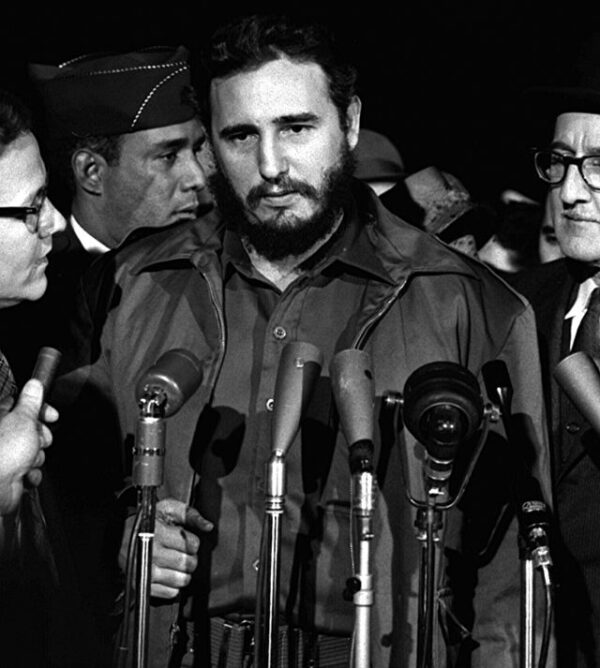

On February 16, 1959, Fidel Castro formally assumed the office of Prime Minister of Cuba, six weeks after the flight of Fulgencio Batista ended his military-backed regime.

Batista had ruled Cuba as an elected president in the early 1940s. But after seizing power in a 1952 coup and canceling scheduled elections, he governed as an authoritarian strongman. Political opposition was suppressed, elements of the constitution were suspended, and the regime relied heavily on the military and internal security forces. By the late 1950s, corruption, censorship, and violent repression had eroded what remained of his legitimacy.

When Batista fled the island on January 1, 1959, Cuba entered a moment of revolutionary upheaval. Castro, leader of the July 26 Movement, had emerged as the dominant figure in the insurgency that helped force the regime’s collapse. Though a provisional government was briefly installed, real authority quickly gravitated toward the revolutionary commander whose forces now controlled the country.

Castro’s ascent had been anything but inevitable. In 1953, he led a failed assault on the Moncada Barracks and was imprisoned. After his release, he regrouped in Mexico, returning to Cuba in 1956 aboard the yacht Granma with a small band of fighters that included Che Guevara. Most were killed or captured shortly after landing. The survivors retreated to the Sierra Maestra mountains, where they waged a guerrilla campaign that steadily expanded as Batista’s army weakened.

By late 1958, the regime was unraveling. Military defeats, loss of public support, and international criticism converged. Batista’s departure triggered a rapid transfer of control to the revolutionary movement.

On February 16, Castro moved from insurgent commander to head of government.

The early rhetoric of the revolution emphasized constitutional restoration and national sovereignty. Public assurances referenced the 1940 constitution and the promise of future elections. But the consolidation of authority began swiftly. Revolutionary tribunals tried former officials and members of Batista’s security forces. Many were executed after expedited proceedings that critics described as lacking due process.

Land reform followed, redistributing large estates and affecting significant American business holdings. Rent reductions and wage decrees proved popular in some sectors. At the same time, independent political actors found their space narrowing. Moderates who had initially served in the provisional government were sidelined. Opposition voices faced mounting pressure. Newspapers encountered censorship.

Castro denied that he was a communist during the early months of 1959. Nonetheless, his government increasingly centralized power and marginalized competing political movements. By 1960, Cuba had nationalized major industries and moved into formal alignment with the Soviet Union, setting the stage for decades of Cold War confrontation.

February 16 did not immediately reveal the full ideological direction of the new regime. But it marked the decisive transfer of state authority into the hands of a revolutionary movement that would soon eliminate political pluralism altogether.

What began as an armed revolt against an authoritarian ruler quickly became a new system defined by one-party control. Castro would remain at the apex of Cuban politics for nearly fifty years, surviving invasion attempts, economic embargoes, and shifting global alliances.