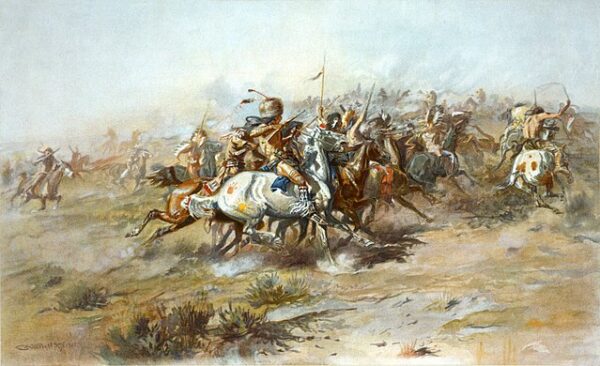

June 25, 1876, saw one of the most famous battles for the American West–one that altered the future of the continent and how the United States conceived itself. On that day, Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer leading the 7th Cavalry, along with their Native American allies, met the Lakota Sioux, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho tribes on along the ridges, steep bluffs, and ravines of the Little Bighorn River, in south-central Montana.

Conflict between the Lakota and Cheyenne and the United States had been growing for years.

The National Parks Service writes, “In 1868, after fierce fighting from 1865-1867 between U.S. Army personnel and Lakota and Cheyenne warriors, several Lakota leaders agreed to sign the Treaty of Fort Laramie. This treaty created a large reservation for the Lakota in the western half of present-day South Dakota; the Lakota’s beloved Black Hills area. The United States wanted tribes to give up their nomadic life which brought them into conflict with other Indians, white settlers and railroads. Agreeing to the treaty meant accepting a more stationary life and relying on government-supplied subsidies.

However, Lakota leaders such as Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse rejected the reservation system. Likewise, many roving bands of hunters and warriors did not sign the 1868 treaty. They felt no obligation to conform to its restrictions, or to limit their hunting to the unceded hunting land assigned by the treaty. Their forays off the set aside lands brought them into conflict with settlers and enemy tribes outside the treaty boundaries.

Tension between the United States and the Lakota escalated in 1874, when Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer was ordered to make an exploration of the Black Hills inside the boundary of the Great Sioux Reservation. Custer was to map the area, locate a suitable site for a future military post, and to make note of the natural resources. During the expedition, professional geologists discovered deposits of gold. Word of its discovery caused an invasion of miners and entrepreneurs to the Black Hills in direct violation of the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie. The United States negotiated with the Lakota to purchase the Black Hills, but the offered price was rejected by the Lakota. The climax came in the winter of 1875, when the Commissioner of Indian Affairs issued an ultimatum requiring all Lakota to report to a reservation by January 31, 1876, or be labeled as “hostiles.” The deadline came with virtually no response from the Indians, and matters were handed to the military.

General Philip Sheridan, commander of the Military Division of the Missouri, devised a strategy that committed several thousand troops to find and to engage the “hostile” Lakota and Cheyenne, with the goal of forcing their return to the Great Sioux Reservation. The campaign was set in motion in March of 1876, when a 450-man force of combined cavalry and infantry commanded by Colonel John Gibbon, marched out of Fort Ellis near Bozeman, Montana. General George Crook set out from Fort Fetterman in central Wyoming Territory with around 1,000 cavalry and infantry in late May. A few weeks before that, General Alfred Terry left from Fort Abraham Lincoln in Bismarck (Dakota Territory) with 879 men. The bulk of this force was the 7th Cavalry, commanded by Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer.

It was expected that any one of these three forces would be able to deal with the 800-1,500 warriors they likely were to encounter.

Those expectations proved to be disastrously wrong for the Army. “As the Battle of the Little Bighorn unfolded, Brittanica describes, “Custer and the 7th Cavalry fell victim to a series of surprises, not the least of which was the number of warriors that they encountered. Army intelligence had estimated Sitting Bull’s force at 800 fighting men; in fact, some 2,000 Sioux and Cheyenne warriors took part in the battle. Many of them were armed with superior repeating rifles, and all of them were quick to defend their families. Native American accounts of the battle are especially laudatory of the courageous actions of Crazy Horse, leader of the Oglala band of Lakota. Other Indian leaders displayed equal courage and tactical skill.

Cut off by the Indians, all 210 of the soldiers who had followed Custer toward the northern reaches of the village were killed in a desperate fight that may have lasted nearly two hours and culminated in the defense of high ground beyond the village that became known as “Custer’s Last Stand.” The details of the movements of the components of Custer’s contingent have been much hypothesized. Reconstructions of their actions have been formulated using both the accounts of Native American eyewitnesses and sophisticated analysis of archaeological evidence (cartridge cases, bullets, arrowheads, gun fragments, buttons, human bones, etc.), Ultimately, however, much of the understanding of this most famous portion of the battle is the product of conjecture, and the popular perception of it remains shrouded in myth.

Atop a hill on the other end of the valley, Reno’s battalion, which had been reinforced by Benteen’s contingent, held out against a prolonged assault until the next evening, when the Indians broke off their attack and departed. Only a single badly wounded horse remained from Custer’s annihilated battalion (the victorious Lakota and Cheyenne had captured 80 to 90 of the battalion’s mounts). That horse, Comanche, managed to survive, and for many years it would appear in 7th Cavalry parades, saddled but riderless.”

The Battle of Little Bighorn revealed the height of Indian power and served as a pinnacle moment in the relations between the United States and Native American groups. However, its impact on white Americans was so profound that it led to a swift and forceful response from federal troops, which ultimately led to the conquering of the West by the United States. The significance of this historic event is recognized and remembered through the establishment of the Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument in 1946 and the subsequent addition of the Indian Memorial in 2003. These commemorations serve as lasting reminders of the battle’s enduring legacy.

At mid-day on June 25,” writes The History Channel, “Custer’s 600 men entered the Little Bighorn Valley. Among the Native Americans, word quickly spread of the impending attack. The older Sitting Bull rallied the warriors and saw to the safety of the women and children, while Crazy Horse set off with a large force to meet the attackers head on. Despite Custer’s desperate attempts to regroup his men, they were quickly overwhelmed. Custer and some 200 men in his battalion were attacked by as many as 3,000 Native Americans; within an hour, Custer and all of his soldiers were dead.”

The Native American victory at Little Bighorn was a major blow to the U.S. Army and became an iconic event in the history of the American West. It sparked a renewed determination by the U.S. government to exert control over Native American tribes and intensified military campaigns against them. The battle also fueled public interest and curiosity about the “Wild West” and the conflict between settlers and Native Americans.