Hungry sailors are not to be trifled with. That’s what happened aboard the Russian battleship the Potemkin on June 27, 1905. Spoiled meat sparked a storm of rebellion that echoed across revolutionary-minded Russia.

The US Naval Institute helps contextualize things: “For a century before 1905, Imperial Russia was boiling with unrest. The people suffered under the oppressive rule of an absolute monarchy. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, fifteen million serfs were working for 130,000 landowners, of whom the greatest was the Tsar. In December 1825, the safety valve lifted when the guards at St. Petersburg mutinied (the Decembrists). Nicholas I then tried to substitute discipline for freedom, and agrarian outbreaks were soon renewed. Though each was suppressed with bloody brutality, by the middle of the century as many as a hundred such disturbances were reported annually.

Alexander II, wiser than his predecessors, realized the need for reform. The serfs were freed in 1861, and the system of government by autocracy was modified. All power remained in the hands of the Tsar and the rich landowners, administered by a strong bureaucracy of officials and supported by the Orthodox Church, but elected county assemblies and town councils were authorized. These steps were not, however, enough. When Alexander II’s flirtation with liberalism was brought to an end by his assassination in 1881, his successor had to deal with more than country disturbances. The beginnings of industry in Russia had produced a concentration of factory workers in the cities. There were serious strikes in St. Petersburg and elsewhere in 1882 and again in 1895 and 1896. The people had no other way of demanding relief from want as well as oppression, for those who held the power and the wealth paid wages below subsistence level.

With some crew members filled with revolutionary fervor, the scene was set for the Russian sailors to say enough is enough.

“Morale in Russia’s Black Sea fleet had long been at rock-bottom lows, spurred on by defeats in the Russo-Japanese War and widespread civil unrest on the homefront, writes The History Channel. Many navy ships were teeming with revolutionary sentiment and animosity toward the aristocratic officer class. One of the Potemkin’s lead radicals was Afanasy Matyushenko, a fiery quartermaster known for railing against the brutal discipline of navy life. In early June 1905, he and Potemkin crewman c joined with other disgruntled sailors in plotting a fleet-wide mutiny. Their audacious plan called for the rank and file to rise up and strike a concerted blow against the officers. After commandeering all the navy ships in the Black Sea, the conspirators would enlist the peasant class in a revolt that would sweep Czar Nicholas II from the Russian throne.

The mutiny was scheduled to begin in early August aboard the fleet flagship, but events conspired to see that Potemkin took the starring role. The trouble began on June 27, a few days after the ship set sail from Sevastopol to conduct practice maneuvers. That morning, a group of conscripted crewmen discovered that the beef intended for their lunchtime borscht was crawling with maggots. The sailors complained to their officers, but after an inspection by the ship’s doctor, the meat was deemed suitable for consumption. The Potemkin’s 763-man crew was left seething with rage. Led by Matyushenko and Vakulenchuk, they resolved to protest by refusing to eat the tainted food.

When lunch came and Potemkin’s crew ignored the vats of borscht, Captain Yvgeny Golikov had them line up on the main deck. He and his short-tempered first officer Ippolit Gilyarovsky both suspected the protest was tied to revolutionary factions lurking in the bowels of the ship, and they were determined to single out the ringleaders for punishment. After threatening the men with death, Golikov gave a simple order: “Whoever wants to eat the borscht, step forward.” Many sailors lost their nerve and complied, but the hard-liners stubbornly held their ground. When Golikov called out the ship’s marine guards—a sign that he was prepared to resort to a firing squad—a few of the conspirators broke rank and took cover at a nearby gun turret. “Enough of Golikov drinking our blood!” Matyushenko bellowed to his fellow sailors. “Grab rifles and ammunition…Take over the ship!”

Before the officers could react, Matyushenko, Vakulenchuk and a few others ran to the weapons room and armed themselves. A vicious firefight broke out when they tried to force their way back onto the deck. First Officer Gilyarovsky succeeded in mortally wounding Vakulenchuk, but he and several other loyalists were promptly gunned down and pitched overboard. As the battle raged, Potemkin’s stunned officers found that very few of the ship’s marines and conscripted sailors were willing to come to their aid. Matyushenko and his revolutionaries took advantage of the chaos and fanned out across the ship. After 30 frantic minutes, they had commandeered both Potemkin and the Ismail, a small torpedo boat that served as its escort ship. The surviving officers were rounded up and placed under guard. Captain Golikov was shot dead after he was found hiding in a stateroom.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OtfsxK3zMeU

During the mutiny, Vakulenchuk was shot and killed by the ship’s officers in the early stages of the uprising. His death further fueled the determination of the mutineers and added to the significance of the events that unfolded.

As more and more of the crew joined in, the mutineers killed the captain, the doctor and several other officers before locking the remaining officers in their cabins. Soon the Potemkin hoisted a red flag and the crew formed a ‘people’s committee’ and chose to head toward Odessa, which has already begun experiencing revolutionary activity among the working people who had been on strike for two weeks.

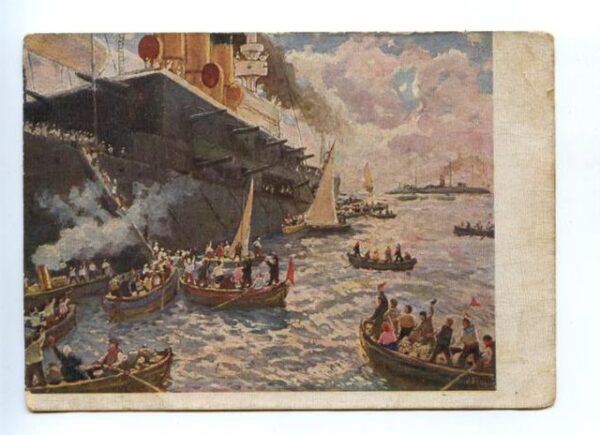

One historian writes, “People began to gather at the waterfront after the Potemkin arrived in the harbour at 6 am on the 15th. Valenchuk’s body was brought ashore by an honour guard and placed on a bier close to a flight of steps which twenty years afterwards would play an immortal and immensely magnified role in the famous ‘Odessa steps’ sequence of Sergei Eisenstein’s film. A paper pinned on the corpse’s chest said, ‘This is the body of Valenchuk, killed by the commander for having told the truth. Retribution has been meted out to the commander.’

Citizens brought food for the seamen and flowers for the bier. As the day wore on and word spread, the crowd steadily swelled, listening to inflammatory speeches, joining in revolutionary songs and some of them sinking considerable quantities of vodka. People began looting the warehouses and setting fires until much of the harbour area was in flames.

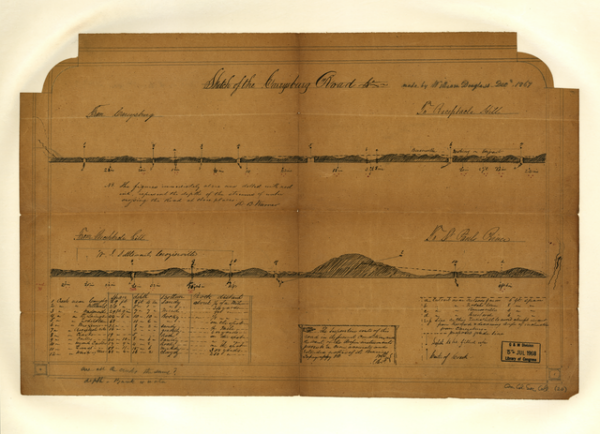

The crew were hoping to provoke mutinies in other ships of the Black Sea fleet, but there were only a few minor disturbances, easily put down. The mutineers sailed west to the Romanian port of Constanza for badly needed fresh water and coal, but the Romanians demanded that they surrender the ship. They refused and sailed back eastwards to Feodosia in the Crimea, where a party landed to seize supplies, but was driven off.”

Soon after, the Potemkin had no choice by to sail back to Romania. They needed supplies. Once there they surrendered the ship to authorities and it was returned to Russian naval leaders.

Although it didn’t ultimately succeed, the mutiny of the Potemkin and Vakulenchuk’s death became a powerful symbol of the struggle against oppression and an inspiration for subsequent revolutionary movements, eventually leading to the overthrow of the czar entirely.