Pickett’s Charge, often heralded as the high-water mark of the Confederacy, stands as one of the most dramatic and poignant moments in American Civil War history. On the afternoon of July 3, 1863, during the third and final day of the Battle of Gettysburg, this audacious assault unfolded—a gamble that would seal the fate of the Confederate Army and alter the course of the war.

The Battle of Gettysburg was a desperate clash between the Union Army of the Potomac, led by Major General George G. Meade, and the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, commanded by General Robert E. Lee. After two days of brutal fighting, Lee believed a decisive blow to the Union center at Cemetery Ridge could shatter their defenses and bring about a Confederate victory, potentially forcing the Union to seek peace.

Lee’s plan hinged on a massive artillery barrage intended to soften the Union defenses. At 1 p.m., over 150 Confederate cannons opened fire, creating a thunderous roar and a smoky haze that enveloped the battlefield. For two relentless hours, the earth shook under the barrage, yet its effectiveness was questionable. Many Confederate shells overshot their targets or fell harmlessly behind the Union lines, while Union artillery responded with a fierce counter-barrage.

Despite the limited success of the bombardment, Lee pressed on with the infantry assault. Around 3 p.m., approximately 12,500 Confederate soldiers stepped off, forming a line nearly a mile wide. This force, comprising divisions led by Major General George Pickett, Major General Isaac R. Trimble, and Brigadier General J. Johnston Pettigrew, began their fateful march across the open fields toward Cemetery Ridge.

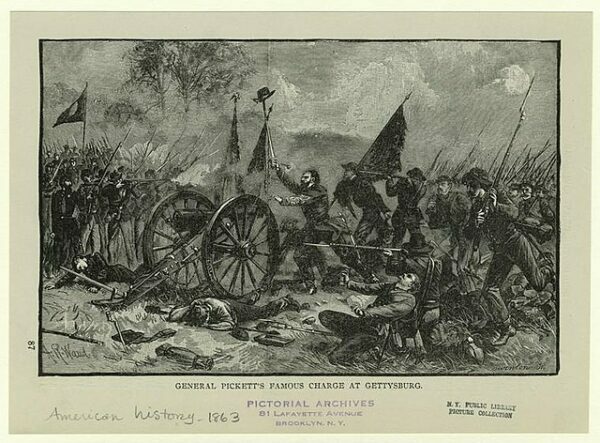

The sight was both magnificent and terrifying. The Confederates advanced in disciplined lines, bayonets gleaming in the sunlight. But as they crossed the open ground, they were met with a withering storm of artillery and rifle fire from the entrenched Union troops. The fields became a killing ground, with cannonballs and musket shots tearing through the Confederate ranks.

Yet, amidst the chaos and carnage, the Confederate soldiers pressed on, driven by duty and resolve. They endured devastating losses, their lines thinning with each step. As they neared the Union position, they faced an even more intense barrage of musket fire from the infantry behind stone walls and earthworks.

A portion of the Confederate forces reached the Union lines, and fierce hand-to-hand combat erupted near a small copse of trees, later known as the “High Water Mark of the Confederacy.” The struggle was brutal, with soldiers fighting desperately for every inch of ground. Despite their courage and determination, the Confederate assault began to falter. Union reinforcements poured in, and the defenders held their ground with unyielding tenacity.

The tide turned rapidly. The Confederate divisions, decimated and leaderless, began to fall back. What had started as a grand and hopeful charge devolved into a chaotic and bloody retreat. In less than an hour, the assault had turned into a catastrophic defeat, with approximately 6,000 Confederate casualties left on the field.

As the remnants of Pickett’s, Trimble’s, and Pettigrew’s divisions staggered back to their lines, General Lee rode out to meet them. He took full responsibility for the defeat, consoling his shattered troops and acknowledging the grave miscalculation that had led to such a devastating loss.

Pickett’s Charge marked the end of the Battle of Gettysburg, a Union victory that, along with the fall of Vicksburg on the Mississippi River, became a turning point in the Civil War. The Confederate hopes for a decisive victory on Northern soil were dashed, and the momentum of the war shifted irrevocably in favor of the Union.