On June 30, 1882, a presidential assassin met his fate following his shooting of President James Garfield, a wound that eventually killed the 20th president.

The National Parks service explains that even by nineteenth-century standards, “Guiteau was obviously mentally ill. He considered himself a loyal Republican, and his narcissistic personality convinced him that his work for the party was critical to Garfield’s election to the presidency in 1880. In fact, Guiteau had made just a few speeches in New York to small and disinterested crowds; the speech itself, which he originally prepared based on the assumption that Ulysses S. Grant would be the presidential nominee, was nonsensical. Guiteau simply went through the speech, crossing out any mention of Grant’s name and replacing it with Garfield’s.

When Garfield took office in early 1881, Guiteau made his way to Washington to collect his reward: a plum patronage job that he was sure was his for the taking. He visited both the White House and the State Department on multiple occasions to plead his case for an overseas posting to Paris or Vienna. Clearly unqualified, he eventually so annoyed Secretary of State James Blaine that Blaine angrily told him, “Do not ever mention the Paris consulship to me again!”

Garfield was soon embroiled in a very public squabble with New York’s powerful senior Senator, Roscoe Conkling, over the nation’s most coveted patronage job: Collector of the Port of New York. Conkling eventually resigned from the Senate to protest Garfield’s choice for the job. Convinced that Garfield was going to destroy the Republican Party by scrapping the patronage system, Guiteau decided the only solution was to remove Garfield and elevate Vice President Chester A. Arthur—a Conkling acolyte—to the presidency. This would not only save the party, but would also result in Guiteau receiving the patronage job he believed was rightfully his. Surely a grateful President Arthur would reward Charles Guiteau.”

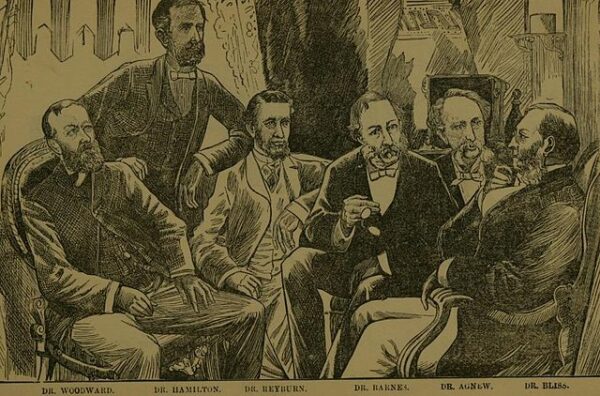

The assassin’s plan did not work. A strong midwesterner and general during the Civil War, Garfield held on for nearly three months after being shot. Most historians today agree that he died only after suffering terrible medical from doctors who did not believe in germ theory, and thus didn’t sterilize their equipment (or fingers) as they prodded the poor president looking for Guiteau’s bullet.

Held in custody for the duration, after Garfield finally died on September 19, the government put Guiteau on trial for murder. At trial, the assassin Guiteau stated, “I did not kill the President. The doctors did that. I merely shot him.”

The jury did not agree, and after a trial that lasted nearly two months and often had a circus-like atmosphere, Guiteau was convicted of murder in January 1882.

“Guiteau, age thirty-nine at the time,” writes The Miller Center, “was known around Washington as an emotionally disturbed man. He had killed Garfield because of the President’s refusal to appoint him to a European consulship. In planning this violent act, Guiteau stalked Garfield for weeks. On the day Garfield died, Guiteau wrote to now President Chester A. Arthur, “My inspiration is a godsend to you and I presume that you appreciate it. . . . Never think of Garfield’s removal as murder. It was an act of God, resulting from a political necessity for which he was responsible.” At his trial, the jury deliberated one hour before returning a guilty verdict. Sentenced to be hanged, Guiteau climbed the scaffold on June 30, 1882, convinced that he had done God’s work.

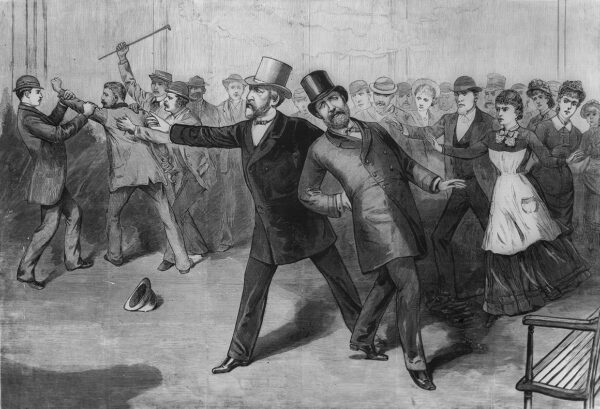

Guiteau was led to the gallows and executed for murder. Guiteau was no ordinary killer, though: his victim was James A. Garfield, the twentieth President of the United States. Guiteau stalked President Garfield around Washington, D.C. for several weeks before shooting him in a train station on July 2, 1881. Garfield had been president for just four months.