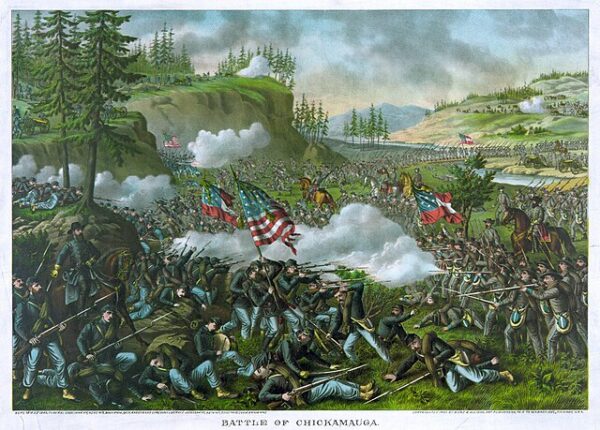

The Battle of Chickamauga, fought between September 19 and 20, 1863, marked one of the major conflicts of the American Civil War, involving the Union Army of the Cumberland and the Confederate Army of Tennessee. The battle took place in northwestern Georgia, near Chickamauga Creek, just a few miles south of Chattanooga, Tennessee. It was a pivotal engagement as both sides sought to control Chattanooga, a vital transportation hub and gateway to the Deep South. By the time the dust settled, the Battle of Chickamauga would become the second deadliest battle of the Civil War, only surpassed by Gettysburg in terms of casualties.

The stage for the battle was set in the summer of 1863. Union Major General William Rosecrans had been leading the Army of the Cumberland in a successful campaign to push Confederate forces under General Braxton Bragg out of middle Tennessee and into Georgia. Rosecrans’ maneuvering forced Bragg to abandon the strategic city of Chattanooga without a fight, a significant Union victory. However, Bragg, reinforced by troops from Virginia under Lieutenant General James Longstreet, was determined to retake Chattanooga.

On September 18, 1863, Bragg began positioning his forces along the banks of Chickamauga Creek, aiming to strike Rosecrans’ army before it could concentrate its forces. Bragg’s plan was to cut off the Union army’s escape route back to Chattanooga, trapping them in Georgia. On the morning of September 19, the battle commenced when Union forces under Brigadier General George Thomas clashed with Confederate troops in the dense forests surrounding the creek. The fighting quickly escalated into a chaotic and bloody struggle, as both sides poured more men into the fray.

One of the defining features of the Battle of Chickamauga was the terrain. The dense woods and underbrush made communication and coordination difficult for both armies. Soldiers often fought at close range, with little visibility of their surroundings. This confusion led to frequent shifts in momentum, with each side gaining and losing ground throughout the first day of battle. By the evening of September 19, neither side had gained a clear advantage, though the Union army was in danger of being enveloped by the Confederates.

On September 20, Bragg launched a full-scale assault on the Union lines. His forces, including Longstreet’s reinforcements, attacked with ferocity. Rosecrans, mistakenly believing a gap had opened in his line, shifted troops to fill the nonexistent breach, inadvertently creating a real gap in his defenses. Longstreet’s men exploited this mistake, driving through the Union lines and causing a large portion of the Army of the Cumberland to retreat in disarray.

Despite the breach, the Union left, commanded by General George Thomas, stood firm. Thomas quickly organized a defense on Snodgrass Hill, repelling wave after wave of Confederate attacks. His steadfastness earned him the nickname “The Rock of Chickamauga.” For several hours, Thomas’s men held the line, buying time for the rest of the Union army to retreat to Chattanooga. As night fell, Thomas’s forces finally withdrew, and the Battle of Chickamauga came to an end.

The aftermath of the battle was grim. The Union suffered over 16,000 casualties, while the Confederates lost around 18,000 men, making Chickamauga one of the bloodiest battles of the Civil War. Although the Confederates emerged as the victors, they failed to follow up on their success. Bragg did not pursue the retreating Union forces, allowing Rosecrans to regroup and fortify Chattanooga. This would set the stage for the subsequent Battles for Chattanooga, where Union forces would ultimately emerge victorious.

In the end, the Battle of Chickamauga was a tactical victory for the Confederates, but a strategic failure. Bragg’s inability to capitalize on his triumph allowed the Union to maintain control of Chattanooga, a key city that would later serve as the launching point for General William T. Sherman’s Atlanta Campaign and March to the Sea, further tightening the Union’s grip on the Confederacy.