On a crisp autumn day, October 4, 1853, the Ottoman Empire, weakened but defiant, declared war on the Russian Empire, igniting what would become one of the most significant conflicts of the 19th century—the Crimean War. For decades, the Ottoman Empire had been struggling to maintain its vast territories, its influence waning under the weight of internal strife and external pressure. To the north, Tsar Nicholas I of Russia saw opportunity. He sought to expand Russian influence over the Ottoman lands, particularly the warm-water ports of the Black Sea, and to assert control over the Christian Orthodox populations under Ottoman rule.

The conflict had been simmering for months. At the heart of the initial dispute was a seemingly minor disagreement over Christian holy sites in Jerusalem, a city controlled by the Ottoman Empire. The Catholic Church, backed by France, and the Russian Orthodox Church both laid claim to protective rights over these sacred places. The Ottoman Sultan’s decision to side with the Catholics infuriated Tsar Nicholas, who used the dispute as a pretext to further Russia’s ambitions. The real prize, however, was far greater than Jerusalem—it was dominance over the Balkans, the Black Sea, and control of trade routes to the Mediterranean.

Tensions boiled over when Russian forces occupied the Danubian Principalities—modern-day Romania—directly challenging Ottoman sovereignty. The Ottoman Empire, struggling to hold itself together, turned to its traditional rivals, Britain and France, seeking their support against Russian aggression. Britain, with its vast empire and control of global trade routes, feared Russian expansion would threaten its interests in India and the Middle East. France, under Napoleon III, saw an opportunity to assert itself as a dominant European power by opposing Russia.

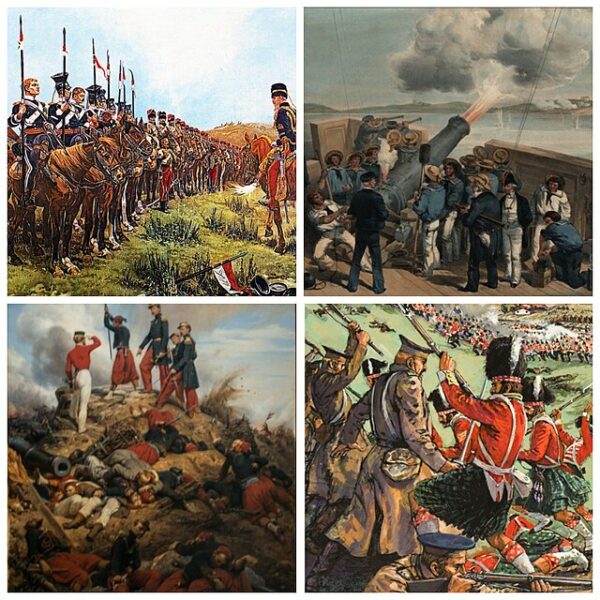

When the Ottomans officially declared war on Russia, the first shots were fired along the Danube River, but soon the conflict spread to the Black Sea. Russian forces attempted to dominate the Ottoman fleet, leading to the first major clash at the Battle of Sinop in November 1853, where Russian ships destroyed much of the Ottoman navy. This decisive victory, however, only served to draw Britain and France into the war. Both nations declared war on Russia in early 1854, transforming the Crimean conflict into a full-scale European war.

The eyes of the world soon turned to the Crimean Peninsula, where the most brutal and defining battles would take place. For Tsar Nicholas, control of Sevastopol, Russia’s key naval base on the Black Sea, was vital to his empire’s strategy. For the Western Allies—Britain, France, and the Ottomans—destroying Sevastopol was the key to breaking Russia’s hold over the region. In September 1854, British and French troops landed on Crimea’s western shores, beginning the long, bloody siege of Sevastopol that would last nearly a year.

The siege of Sevastopol became a grim test of endurance. Russian defenders, entrenched behind their fortifications, fought fiercely to hold the city, while British, French, and Ottoman forces suffered heavy casualties in their attempts to breach the defenses. Disease ravaged the soldiers on both sides, with cholera and dysentery claiming more lives than bullets and bayonets. The cold winter months turned the battlefield into a frozen, hellish landscape. Yet, amid the carnage, the war gave rise to figures of heroism and innovation. Florence Nightingale, a British nurse, emerged as a pioneer in modern medical care, her efforts to improve sanitation saving countless lives.

By the time Sevastopol fell to the Allies in September 1855, the war had devastated all sides. The Treaty of Paris in 1856 officially ended the conflict, forcing Russia to abandon its ambitions in the Black Sea and reaffirming the Ottoman Empire’s tenuous hold over its territories. For Russia, the war revealed the weaknesses of its outdated military and feudal society, prompting internal reforms. For the Ottomans, the war delayed but did not prevent the empire’s slow decline. Britain and France, though victorious, saw the war as a grim reminder of the human cost of European power struggles.