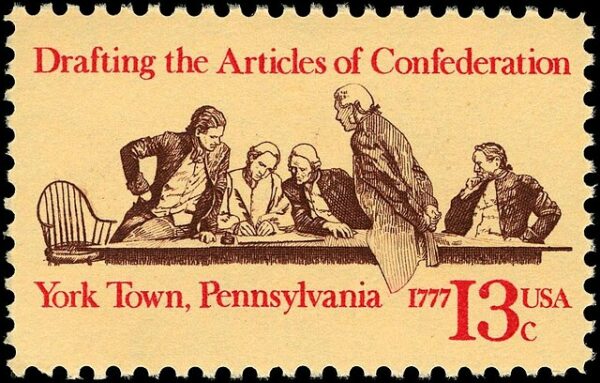

The Articles of Confederation, adopted by the Continental Congress on November 15, 1777, and submitted to the states for ratification two days later on November 17, marked a crucial step in the formation of the United States. As the first framework for a unified national government among the thirteen original colonies, the Articles emphasized state sovereignty and a decentralized federal system. While ultimately replaced by the U.S. Constitution in 1789, they played a vital role in highlighting the challenges of uniting diverse states under a single government during and after the Revolutionary War.

Drafted amidst the war for independence, the Articles reflected the colonies’ deep distrust of centralized authority, rooted in their experiences under British rule. The document intentionally established a loose confederation of independent states bound together by a weak central government. The national Congress was granted specific powers, including conducting foreign diplomacy, declaring war, managing relations with Native American tribes, and overseeing the Western territories. However, these powers were limited, requiring the approval of the states for effective implementation.

Most governing authority remained with the states, which retained their independence in all areas not explicitly delegated to Congress. Representation in Congress was equal for all states, regardless of population or size, with each state holding one vote. While this system aimed to ensure fairness, it often hindered decision-making. Significant measures needed the approval of nine states, and amendments required unanimous consent, making it difficult to enact change or address pressing issues.

Ratification of the Articles was not immediate. Disputes over Western land claims delayed agreement among the states. Larger states like Virginia and New York, with extensive claims, faced resistance from smaller states like Maryland, which feared an imbalance of power. Eventually, compromises were reached, including the cession of certain Western lands to the central government. Maryland’s ratification on March 1, 1781, completed the process, officially enacting the Articles as the governing framework of the United States.

Despite providing a foundation for cooperation during the Revolutionary War, the Articles’ weaknesses soon became evident. The central government lacked the power to levy taxes or regulate commerce, leaving it dependent on voluntary state contributions, which were often insufficient. Additionally, Congress had no authority to enforce laws or maintain a standing army, further undermining its effectiveness.

After the war, these limitations became even more problematic. Economic instability, trade disputes between states, and the government’s inability to quell uprisings like Shays’ Rebellion in 1786 underscored the need for a stronger federal structure. These challenges led to the Constitutional Convention in 1787, where the Articles were set aside in favor of drafting the U.S. Constitution.

Despite its flaws, the Articles of Confederation achieved important successes. They provided a framework for negotiating the Treaty of Paris in 1783, which ended the Revolutionary War and secured international recognition of American independence. The Articles also laid the groundwork for the orderly expansion of the United States, including the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, which established guidelines for admitting new states and prohibited slavery in the Northwest Territory.

The submission of the Articles of Confederation for ratification in 1777 stands as a significant milestone in American history. While ultimately inadequate for governing a growing nation, the Articles served as a critical learning experience, paving the way for the development of a stronger federal system under the U.S. Constitution that Americans enjoy today.