John Brown’s hanging on December 2, 1859, was a moment of profound historical significance, symbolizing the deep divisions over slavery in pre-Civil War America. The execution occurred in Charles Town, Virginia (now West Virginia), just weeks after his failed raid on the federal armory at Harpers Ferry. Brown’s death transformed him from a controversial figure into a martyr for the abolitionist cause, solidifying his legacy and fueling tensions between North and South.

The raid on Harpers Ferry, which Brown led with the goal of inciting a massive slave rebellion, had ended in failure. Brown and his small band of followers were quickly overwhelmed by U.S. Marines led by Colonel Robert E. Lee. Captured, wounded, and taken into custody, Brown was charged with treason against the state of Virginia, inciting a slave insurrection, and murder. His trial, held in Charles Town, attracted widespread attention. Despite the certainty of his conviction, Brown used the proceedings as a platform to advocate for the abolition of slavery, delivering impassioned speeches that resonated deeply with Northern audiences. Southerners, on the other hand, viewed him as a dangerous radical whose actions threatened their way of life.

Once sentenced to death, Brown spent the final weeks of his life in jail, writing letters and receiving visitors. His words during this time further cemented his status as a symbol of resistance. Calm and composed, Brown expressed no regret for his actions, insisting that his campaign against slavery was righteous and necessary. His resolve and moral conviction impressed even some of his detractors, though they did little to sway Southern opinion, which overwhelmingly supported his execution.

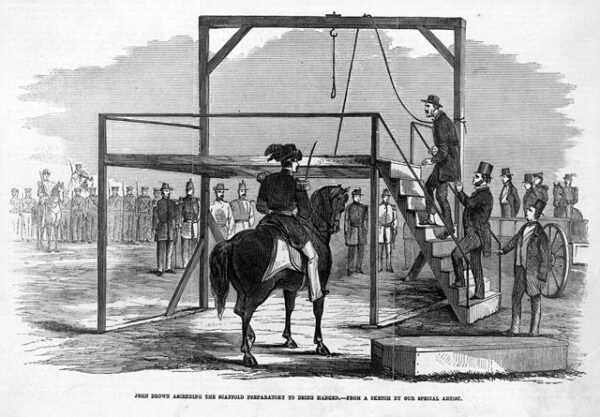

The day of Brown’s hanging dawned cold and somber. Authorities in Charles Town were on high alert, fearing a potential rescue attempt by Northern sympathizers. The town was fortified with hundreds of armed troops, and additional precautions were taken to ensure that the execution proceeded without incident. Despite these fears, the event unfolded without disruption.

Shortly before his death, Brown handed a note to a guard that would become one of his most famous statements: “I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood. I had, as I now think, vainly flattered myself that without very much bloodshed it might be done.” These words foreshadowed the violence and bloodshed of the Civil War, which would begin less than two years later.

At approximately 11 a.m., Brown was led to the gallows. Witnesses described him as composed and unflinching. The crowd that had gathered to watch the execution reportedly observed in somber silence, with little evidence of jubilation. When the trapdoor was released, Brown fell to his death. He was pronounced dead within minutes, his body left to hang briefly before being cut down.

The execution was intended to send a clear message to those who might consider further rebellion, but it had the opposite effect. For many Northerners, Brown’s death elevated him to the status of a martyr, a man who had sacrificed his life for the cause of justice and equality. Abolitionists celebrated him in song and prose, with works like “John Brown’s Body” immortalizing his actions while church bells rang. Prominent thinkers such as Ralph Waldo Emerson likened his death to religious sacrifice, claiming it “made the gallows as glorious as the cross.”

In the South, however, Brown’s actions and death exacerbated fears of slave insurrections and deepened hostility toward Northern abolitionists. His raid and execution were seen as proof of Northern aggression, further solidifying Southern resolve to defend slavery.