On December 20, 1989, the United States initiated Operation Just Cause, a military invasion of Panama with the goal of removing Manuel Noriega from power. This event was a significant milestone in U.S.-Latin American relations, demonstrating the American military’s capacity to carry out a large-scale intervention in its sphere of influence. Though the operation achieved its immediate objectives, it sparked widespread debate and left lasting impacts on both countries.

Manuel Noriega, once a U.S. ally and head of Panama’s Defense Forces, became a destabilizing figure in the region by the late 1980s. Initially supported by the CIA for his anti-communist stance during the Cold War, he was later implicated in drug trafficking, corruption, and human rights abuses. Noriega played a central role in facilitating narcotics smuggling for the Medellín cartel, becoming a target of U.S. law enforcement. His refusal to step down, even after being indicted on drug trafficking charges in 1988, further strained relations with Washington.

Tensions reached a boiling point when Noriega annulled the results of the 1989 presidential election, where Guillermo Endara had been declared the winner. His actions provoked widespread protests and violent reprisals by Panamanian security forces. President George H.W. Bush justified the invasion by emphasizing the need to protect American citizens in Panama, curb drug trafficking, and support democratic governance.

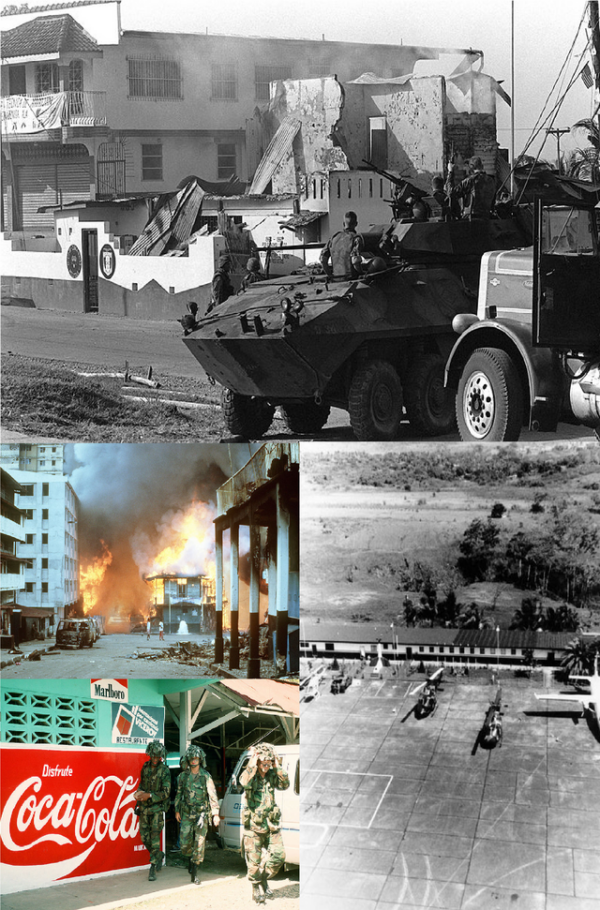

Operation Just Cause commenced in the early hours of December 20, 1989, involving over 27,000 U.S. troops and 300 aircraft. It was the largest American military operation since the Vietnam War, targeting strategic objectives like Noriega’s headquarters, military bases, and the Panama Canal. The fighting was intense but brief, as U.S. forces quickly overwhelmed Panamanian troops using precision airstrikes and coordinated ground assaults. Despite the operation’s swift success, combat in urban areas caused civilian casualties and significant destruction.

Noriega managed to evade capture initially, seeking refuge in the Vatican Embassy in Panama City. After a tense standoff, U.S. forces resorted to psychological warfare, blasting loud rock music outside the embassy to pressure Noriega into surrendering. On January 3, 1990, he gave himself up and was extradited to the United States, where he was convicted of drug trafficking, money laundering, and racketeering, receiving a 40-year prison sentence.

The aftermath of the invasion brought sweeping changes to Panama. Endara was sworn in as president, and efforts to restore democracy and rebuild institutions began. However, the operation also left deep scars, with an estimated death toll ranging from 300 to 3,000, including many civilians. The destruction of homes and infrastructure further complicated Panama’s recovery.

Internationally, the invasion was polarizing. The U.S. framed it as a defense of democracy and a measure against drug trafficking, but critics condemned it as a violation of international law and an infringement on Panamanian sovereignty. The incident also reignited debates about U.S. military interventions in Latin America and their long-term consequences.

Over time, the invasion reshaped U.S.-Panama relations, culminating in the 1999 handover of the Panama Canal to Panama under the Torrijos-Carter Treaties. Noriega’s downfall illustrated the precariousness of Cold War-era alliances and highlighted the risks of supporting authoritarian regimes for strategic gains.