On January 21, 1793, Louis XVI of France, the former king, faced execution by guillotine in Paris’s Place de la Révolution (now Place de la Concorde). This pivotal moment marked the end of absolute monarchy in France and symbolized the revolutionary fervor that had overtaken the nation, influencing both French and world history.

Louis XVI’s downfall was the result of years of political and social upheaval. Born in 1754, he ascended the throne in 1774 and initially sparked hope for reform among the French people. However, his reign was plagued by poor financial decisions, resistance to meaningful change, and a widening gap between the monarchy and the public. The economic crisis of the time, worsened by France’s costly involvement in the American Revolution, left the country in deep debt and fueled public discontent.

During this period of hardship, revolutionary ideas began to take root. Soaring food prices, mass unemployment, and growing resentment toward the privileges of the aristocracy created a volatile climate. In 1789, the Estates-General, an assembly representing France’s three social classes—clergy, nobility, and commoners—was convened to address the financial crisis. However, it quickly transformed into the National Assembly, a body representing the common people and sparking the beginning of the French Revolution.

The Revolution gained momentum as the monarchy struggled to adapt. A key turning point was the storming of the Bastille on July 14, 1789, a powerful symbol of resistance against oppression. The monarchy suffered further damage in 1791 when Louis XVI and his family attempted to escape France. Their capture in Varennes eroded any remaining trust in the king and intensified calls for the abolition of the monarchy.

In 1792, the monarchy was officially abolished, and the French First Republic was declared. Louis, now referred to as Citizen Louis Capet, was put on trial by the National Convention. Charged with treason and conspiracy against the state, he faced evidence of secret communications with foreign powers. Despite his lawyers’ efforts to defend him as a misunderstood ruler, the Convention found him guilty.

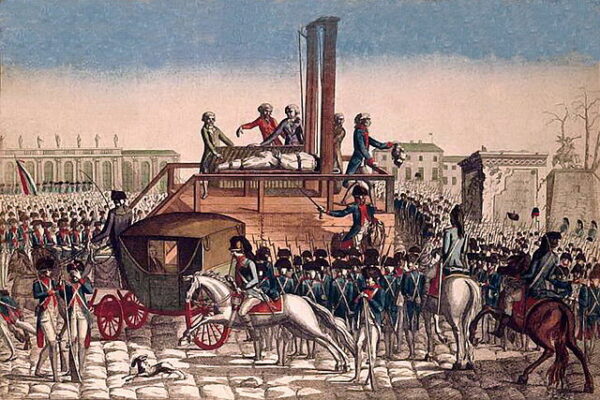

On January 20, 1793, Louis XVI was sentenced to death by a narrow vote. The next day, he was brought to the Place de la Révolution amidst heavy security. Thousands gathered, their reactions ranging from celebration to sorrow. Louis mounted the scaffold with composure and attempted to speak, proclaiming his innocence and offering forgiveness to those who condemned him. His words, however, were drowned out by the sound of drums. Moments later, the guillotine blade fell, ending his life and over a millennium of French monarchy.

The execution reverberated far beyond France. Monarchies across Europe were horrified, viewing it as a direct challenge to their power. This led to the formation of the First Coalition, a military alliance determined to suppress the revolutionary movement.

Domestically, the event had lasting effects. It radicalized the revolution, deepened political divisions, and ushered in the Reign of Terror, a period of mass executions and political purges led by figures like Robespierre. While some saw Louis’s death as a necessary step toward liberty and equality, others viewed it as a grim example of revolutionary excess and mob violence.

Historians continue to debate the legacy of Louis XVI’s execution. For some, it serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of unchecked revolutionary zeal. For others, it represents a decisive moment when the people asserted their sovereignty and broke free from the old regime.