On February 7, 1962, the United States enacted a sweeping trade embargo against Cuba, effectively halting all imports and exports between the two nations. This move was part of a broader effort to isolate Fidel Castro’s revolutionary government following the Cuban Revolution of 1959. Formally established through Executive Order 3447 under the authority of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 and the Trading with the Enemy Act of 1917, the embargo became one of the most enduring and impactful economic sanctions in modern history. Beyond reshaping U.S.-Cuba relations, it played a significant role in Cold War geopolitics and influenced the economic trajectory of both nations.

Before the embargo, Cuba and the United States maintained a deeply intertwined economic relationship, with American businesses dominating key industries such as sugar, tobacco, and tourism. The island relied heavily on American markets, making it a prime destination for U.S. investors. However, the overthrow of U.S.-backed dictator Fulgencio Batista by Fidel Castro’s revolutionary forces in January 1959 set the stage for rapid deterioration in bilateral relations. Castro’s government implemented sweeping land reforms, nationalized foreign-owned industries—including American corporations—and aligned itself with the Soviet Union. These actions alarmed U.S. policymakers, who saw Cuba’s new leadership as a direct threat to American influence in the Western Hemisphere.

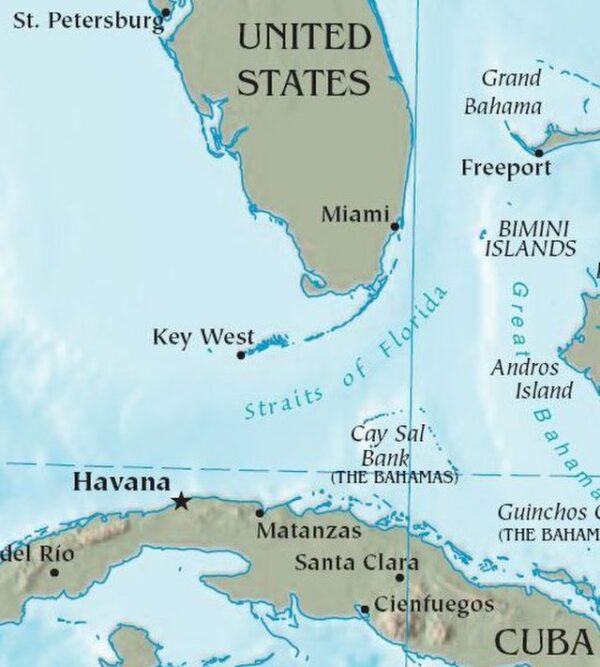

In response, the Eisenhower administration imposed initial economic sanctions in 1960, limiting sugar imports from Cuba and restricting the export of critical goods such as oil. When John F. Kennedy assumed the presidency in 1961, he escalated these measures, culminating in the full-scale embargo imposed in early 1962. The official rationale was to weaken Castro’s regime by creating economic hardship, with the hope that internal dissent would lead to either its collapse or a reduction in its ties to the Soviet Union. Washington also justified the embargo as a response to Cuba’s expropriation of U.S. assets without compensation, viewing it as a violation of international norms. However, the sanctions also served a broader ideological purpose within the Cold War, reinforcing the Monroe Doctrine by signaling that Soviet influence in the Americas would not be tolerated. Additionally, the embargo appeased hardline anti-communists in the United States, particularly Cuban exiles in Florida who advocated for a tough stance against Castro.

The embargo’s effects on Cuba were immediate and far-reaching. The loss of access to American goods and markets forced the island to deepen its economic dependence on the Soviet Union, which provided subsidies, purchased Cuban sugar at favorable prices, and supplied vital resources such as oil. However, this reliance made Cuba vulnerable to fluctuations in Soviet support, a weakness that became evident after the USSR’s collapse in 1991. The ensuing economic crisis, known as the “Special Period,” led to severe shortages of food, medicine, and other essentials. While the Cuban government sought to mitigate the embargo’s effects by expanding trade with other socialist nations and implementing domestic economic adjustments, U.S. sanctions remained a central factor in the country’s ongoing economic struggles. Politically, the embargo also became a useful tool for the Cuban leadership, which framed it as evidence of American aggression and used it to rally domestic support for the revolutionary government.

The embargo had significant consequences beyond Cuba, affecting U.S. businesses and international relations. American companies lost access to a previously lucrative market, while many U.S. allies in Europe and Latin America viewed the embargo as an overreach of American power. The policy became a frequent subject of condemnation in international organizations such as the United Nations, where it was criticized as an unjustified economic blockade. Over time, various U.S. administrations adjusted aspects of the embargo, introducing exceptions for humanitarian aid and limited agricultural exports. However, the core restrictions remained intact, reinforced by legislation such as the Helms-Burton Act of 1996, which made it more difficult for future presidents to lift sanctions without congressional approval.

More than six decades after its implementation, the embargo remains one of the most enduring symbols of U.S.-Cuba hostilities. Despite attempts at diplomatic rapprochement—most notably President Barack Obama’s efforts to restore relations in 2014—the embargo persists, largely due to domestic political considerations in the United States. Critics argue that the policy has failed to achieve its primary goal of regime change and has instead inflicted suffering on ordinary Cubans. Supporters, however, maintain that it remains a necessary tool to pressure the Cuban government on human rights and political freedoms.

The legacy of the embargo is one of prolonged geopolitical confrontation, economic hardship, and the lasting influence of Cold War-era policymaking. Whether it will be lifted in the future remains uncertain, as successive U.S. administrations continue to grapple with the political, economic, and strategic complexities of the U.S.-Cuba relationship.